What happens beyond the gate? Findings from the post-release employment study

Dr Bronwyn Morrison

Principal Research Adviser, Department of Corrections

Jill Bowman

Principal Research Adviser, Department of Corrections

Author biographies:

Bronwyn Morrison has a Ph.D in Criminology from Keele University, UK. She has worked in government research roles for the last 12 years, including at the Department of Conservation, NZ Police, and the Ministry of Justice. She joined Corrections’ Research and Analysis team in March 2015 as a Principal Research Adviser.

Jill Bowman has worked in Corrections’ Research and Analysis team for seven years following a variety of roles in both the private and public sector. She also volunteers at Arohata Prison, teaching quilting to women in the Drug Treatment Unit.

Introduction

Nearly 7,000 people were released from New Zealand prisons in the year to 31 March 2015. Of those released, 44% were re-convicted for an offence committed within a year of release, and 70% of that offending occurred within the first six months after release. As the burgeoning international research literature produced on this topic illustrates, there is a need to better understand what happens to people in the first weeks and months after their release from prison, and identify what factors help or hinder efforts to “go straight” during this time (Garland & Wodahl, 2012; Nugent & Schinkel, 2016; King, 2013; Visher & Travis, 2003; Baldry, 2010; Davis, Bahr & Ward, 2012; Petersilia, 2003; Maruna, 2001; Maruna & Tosh, 2005).

The post-release employment study was directed towards this end. Utilising a multi-phased mixed method approach, it examined the impact of employment (or, more typically, unemployment) on post-release outcomes. In doing so, it sought to understand the relative importance of employment compared to other re-integrative needs, such as accommodation and support; how people obtained employment; the nature, conditions, and sustainability of released prisoners’ employment; and why employment helped some people avoid re-offending and achieve better post-release outcomes, but not others. This article briefly describes some of the overarching findings and implications arising from the research.

Method

Between November 2015 and January 2016, 127 prisoners were interviewed face-to-face close to their release. Prisoners from two women’s prisons and four men’s prisons were included in the study. The interviews included questions about education background, employment experience, pre-prison context, programmes, training and employment completed in prison, and prisoners’ release plans, including questions about participants’ intentions to desist (or not) from offending.

Three-quarters (n=97) of the original sample were subsequently re-interviewed four to six months following their release. The majority of the phase two interviews (n=79) occurred in the community, although 18 participants were re-interviewed from within prison. The second interviews took place in a wide range of locations across New Zealand and examined what had happened to people since their release, and what factors helped or hindered any desistance plans people might have had pre-release.

Overall, 224 interview transcripts were generated across the two phases of interviews. These were fully transcribed, thematically analysed, and then cross-tabulated with administrative data to examine who was doing well (or not) post-release and why, and identify what role employment played in determining post-release success or adversity.

The sample

Of those interviewed at both stages of the project, 72 were male and 25 were female. Just under half identified as Mäori and 12 identified as Pacifica. The average age of participants was 32.8, with the youngest participant being 18 years old and the oldest participant 61 years old.

Participants were most commonly serving sentences for violence (28%), dishonesty (23%), and burglary (15%). A quarter of the sample had a family violence conviction associated with their current sentence, while just under half had a history of family violence perpetration. In terms of department risk measures, 9% were categorised as being at low risk of reconviction and reimprisonment, 65% as medium, and 26% as high risk. On average, people had experienced 11 Corrections-administered sentences at the time of their first interview, 18% had served ten or more prison sentences, and just over a third were serving their first prison sentence. Over three-quarters of participants were completing short sentences (less than two years’ duration), and 16% were released from long sentences (two years or more). Just one participant was serving a life sentence. Most participants were released from prison on general release conditions (69%) or parole conditions (18%). A further 13% of participants were released without any conditions.

Notwithstanding some variations, the overall characteristics of participants were broadly similar to that of the general released prisoner population. Consequently, they would be expected to show similar post-release outcomes.

Results

Many prisoners left prison without firm plans

Of the 127 people interviewed up to a month prior to release, just under half could articulate a solid release plan. Even those who planned to work or study often lacked any concrete idea as to how they were going to find work, or even what type of work or study they might do. A quarter of participants had no accommodation organised, and just under one third anticipated little or no social support following their release. As will be discussed further below, those without definite plans tended to fare much worse post-release.

Employment outcomes

An examination of the employment pathways of participants revealed that for the most part prison did not appear to adversely affect employment status. For instance, over two-thirds of people revealed no change in their employment status before and after their latest imprisonment: 18% of participants working pre-prison returned to work afterwards, while 50% of participants were consistently unemployed. A further 19% unemployed pre-prison were working post-release, and only 13% appeared to be faring worse having being employed pre-prison but unemployed post-release.

Forty-one of the 97 people interviewed post-release had been formally employed for at least one day following their release, and another person was starting work the day after being interviewed. Almost half (n=20) of the 41 people who had had formal work since release had been employed immediately pre-prison. Fourteen of the 41 had always or almost always worked, and 23 had worked intermittently. Only four had never worked or had rarely worked. Over half (n=24) of this group had had definite plans for employment after leaving prison and only two had no plans.

A quarter (n=10) of the 41 people who had had formal employment had returned to a previous employer and around half (n=19) had found work through a friend or a relative. Two people continued with the employment they began on “Release to Work” while they were in prison, a Work and Income work broker assisted one other person into work, and a probation officer assisted another person. The remainder had found work by advertising or responding to advertisements, through agencies, or by direct contact with an employer.

Most had advised their employer of their criminal record. However, two who had not been asked had not volunteered this information, saying they wanted to prove themselves first.

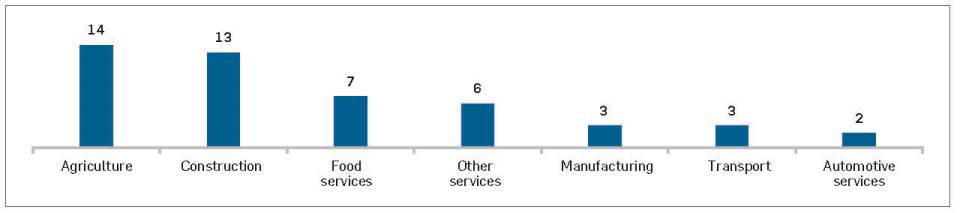

Figure 1 below outlines the nature of participants’ employment. Sixteen had been employed full-time and permanently. Those who had returned to a previous employer were more likely to be in full-time permanent work than those working elsewhere. Nine people worked in seasonal employment, which was finite and could be weather dependent, resulting in variable hours. Several others were employed casually or only part-time. Interviewees in part-time or more casual jobs were earning as little as the minimum wage.

Figure 1:

Nature of employment

Note: Agriculture includes forestry and fishing and covers farming and seasonal fruit/vegetable picking. Construction includes earthmoving, building and painting.

At the time of interview, 27 people were still working. Three were back in prison and the remaining 11 cited the end of seasonal or other temporary work, being bullied by work colleagues, childcare responsibilities, assessing the situation as risky (post-work partying with colleagues), not getting on with family members who were working in the same business, and wanting to establish their own business as reasons for ceasing work. Of the 27 interviewees who were still working, 12 had always or almost always worked – that is, most of those who had always worked who had found work after leaving prison were still in employment several months later.

Twenty-six people who hadn’t had formal work had, however, looked since their release, but blamed their criminal record for their lack of success. A similar number hadn’t looked for work for various reasons, including fulfilling post-release conditions, study, or settling back into the community. Others had no interest in work.

Interviewees thought work was important for keeping themselves occupied, establishing a routine, and for earning more money than they could on a benefit. Several noted it tired them out so they were less inclined to go out at night, thereby avoiding anti-social peers and the possibility of re-offending. A couple of people enjoyed keeping their body active and one person relished being out in the fresh air. One participant identified work as the critical factor helping her turn her life around, and many others acknowledged its importance. For some, work also created both the opportunity and the means for risky behaviour, such as providing money to purchase alcohol and drugs, and buying vehicles for use in illicit activities, as well as more generally socialising with anti-social peers, some of whom were met through work.

Understanding the relative importance of employment compared to other reintegrative needs

As the study progressed it became apparent that employment could not be meaningfully studied in isolation from other reintegrative factors such as accommodation, social support, drug and alcohol use, and mental and/or physical health. Like employment, these factors interacted in complex and varied ways to bring about different outcomes for the research participants. Key findings on the first two of these areas are briefly summarised below.

Post-release accommodation

Accommodation emerged as the single most important reintegration issue for prisoners. With suitable housing, offenders could start to re-establish their lives, including arranging benefits, looking for work, and reconnecting with partners and children. However, a lack of accommodation (often associated with a lack of income) put offenders at a high risk of re-offending, simply to afford life necessities such as food and clothing, or because their only alternative support derived from criminal associates.

Prior to prison, most interviewees lived with a family member or partner, with smaller numbers living with other relatives or friends – sometimes couch surfing. Two people owned their homes and several were renting Housing New Zealand homes.

Only 16 interviewees planned to return to their pre-prison accommodation after their release, demonstrating the transience of this group. Some interviewees could not return to partners because of Protection Orders or the breakdown of relationships, and some families were no longer willing to accommodate participants. Some people in Housing New Zealand rentals were able to retain these while they were in prison when partners or family members were able to take over the lease temporarily. Work and Income declined to allow others to transfer their leases due to drug charges and/or a poor tenancy history requiring them to find alternative accommodation on their release.

Fifteen interviewees had absolutely no idea where they would be living, despite being within a week or two of release, and were finding it difficult to organise accommodation from within prison.

At the post-release interview, 51 of the 97 offenders reported having found somewhere relatively stable to live immediately after their release, the majority with close family members and others with a partner or, in several cases, an ex-partner. Friends and other relatives again provided somewhere to live for most of the remainder. On the other hand, 46 people did not have stable accommodation immediately after release or only had transitional accommodation. Many were in hostels or shelters, with family, partners, ex-partners, other relatives and friends providing temporary support for the rest. Two were living on the streets. Not surprisingly, most of the people who had no confirmed post-release address when they were interviewed in prison were amongst the group whose accommodation in the community was precarious.

By the time of the second interview, just under half of the people in initially precarious accommodation had moved to more suitable housing, often a Housing New Zealand rental, and others had moved in with family or friends. However, three people were on the streets; six people remained in undesirable shelter (including one in a shed); and 18 interviewees were back in prison, either because of new offending or because of a breach of release conditions (including one person whose addresses kept being declined by his probation officer).

Reintegration providers assisted some study participants into accommodation and a number of probation officers had gone to considerable lengths to help people find accommodation, including sometimes driving people to viewings and/or helping secure furniture and appliances once accommodation was obtained.

Post-release support

Following release from prison, the majority of participants received support from either intimate partners (or in some case ex-partners with whom they were still friendly) or close family. As well as emotional support, they were helped with accommodation and financial assistance. A small number of people relied on friends for this support in the absence of partners or family. However, a few participants had nobody close to them they could turn to for help, after the breakdown of relationships or Protection Orders being imposed, or the offender having exhausted the patience of family members. Community Corrections and other agencies, particularly the Salvation Army, played an important role in providing necessities after release and in encouraging desistance where people had no other support. However, gang members, many of whom had resolved to desist from crime while in prison, typically turned to gangs for accommodation and financial help in the absence of other support which led, inevitably, to a downward spiral of drugs, alcohol, and re-offending.

The research also identified that, despite most offenders having children, only a very small number had primary responsibility for their care either before prison or post-release. Most children were living with ex-partners or parents at both points. Interviewees’ involvement with children being cared for by others varied, with some having no contact at all and others seeing them almost daily.

Putting it all together: a post-release outcome framework

To better understand how factors such as employment, accommodation, and support interacted, a post-release outcome framework was developed to identify “successful” outcomes. As international studies demonstrate, defining what counts as a “successful” re-entry, or reintegration outcome is not straightforward (Garland & Wodhal, 2014; Visher & Travis, 2003; Maruna, 2001).

Re-entry is time-bound and focuses on the period immediately following release up to three to 12 months’ post-release (Garland and Wodahl, 2014). It involves the initial adjustment from prison to the community in which a person (re)commences aspects of “normal” life, obtains life necessities (housing, income, transport), accesses emotional support (from families, intimate relationships) and/or (re)connects with children, and preferably refrains from offending and harmful drug and/or alcohol use (Davis, Bahr & Ward, 2012).

Reintegration, on the other hand, involves more fundamental, long-term change. While re-entry is a process all those leaving prison endure, reintegration is neither guaranteed nor time bound. It involves forging new pro-social relationships and avoiding negative ones (Maruna and Roy, 2007), more permanent abstinence from harmful patterns of drug and alcohol use, and ongoing engagement in employment, study, or some other form of purposeful activity, achieving stable and sustainable housing, functionally managing mental health problems, and attempting to achieve or maintain a crime-free lifestyle (Maruna, 2001; Davis, Bahr & Ward, 2012). Reintegration is also generally agreed to involve a more permanent psychological change based on envisioning a new identity (or reclaiming an old one) as a socially-integrated citizen (Farrall, 2004; Maruna, 2001). It is often best understood as a process or continuum rather than a static goal, and can coincide with re-offending, although such behaviour would be expected to diminish as a person moves further along the reintegration continuum, albeit not necessarily in a linear direction (Piquero, 2004).

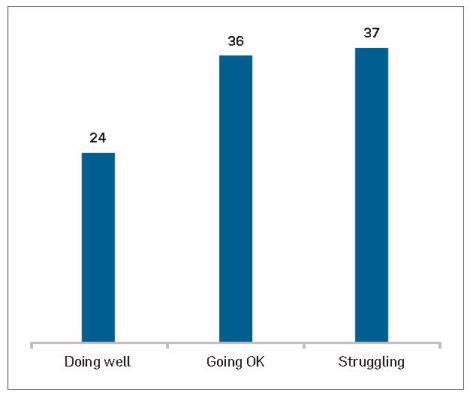

Figure 2:

Post-release outcomes

Taking these observations on board, and in an attempt to assess how well people were doing overall in the four to six months since release, the current study developed and applied a post-release outcome framework. The framework took into account a variety of factors, including more objective measures, such as re-offending, re-imprisonment, sentence compliance, employment status, accommodation status, access to social support, drug and alcohol use, and progress relative to individual past, alongside more subjective aspects such as: people’s sense of agency, strength and realism of future plans, resolve to desist from crime, attitudes to employment (or benefit dependency) and job satisfaction, perceived financial stability, and people’s general sense of wellbeing and outlook on life. Consequently, it was not simply the “fact” of people’s re-offending that mattered, but also their attitudes to such offending and the degree to which they believed this impacted on their plans to ultimately “go straight”. On this basis, people were categorised as “doing well”, “going OK” or “struggling”. As shown in Figure 2, a quarter (n=24) of participants were subsequently assessed as “doing well”, 36 were “going OK” and a similar number were “struggling” (n=37). The following sections briefly outline each of these categories.

Doing well

Those “doing well” tended to be slightly younger, they were also more likely to be male and identify as European. They had generally entered prison with better prospects than other groups, having left school with more qualifications and having far more substantive employment histories. Half of this group had been employed immediately prior to their phase one incarceration and most identified themselves as “good workers”. They were less likely to report mental health problems either prior to or during their incarceration and were more likely to be in regular contact with their children prior to arriving in prison.

Leading up to release, this group tended to have firm release plans in place, with many planning to return to either the same or similar jobs, and a third reported having post-release jobs already confirmed. On the back of established employment backgrounds, these people often had good pre-existing employment networks they could leverage for job opportunities. They typically anticipated high levels of social support and had accommodation organised. They tended to have taken an active role in planning their release and exhibited high levels of personal agency. Consequently, most within this group needed little assistance to find work or accommodation post-release, and few derived additional benefits from employment and training opportunities provided in prison, having already firmly established expertise in their chosen field.

Post release, people within this group were busy. Most were either employed or engaged in some other form of purposeful activity (such as voluntary work). Those who were employed often worked long hours (up to 80 hours a week) and considered their job to be a “good” one. They reported receiving good pay and enjoying high levels of flexibility from employers to accommodate probation commitments. Many derived a sense of legitimacy from their employment, which, in turn, helped catalyse the formation of a new identity, away from offender to “normal” citizen:

I don’t want my kids to know about my time. I want them to know about who I am becoming and, you know, the person I’m going to be … I want them to grow up with a good work ethic … the legit life is better for me (Pacific male in his 20s, formerly in prison for burglary).

Employment operated to restrict the time and energy available for “getting into trouble”, and distanced people from unemployed, anti-social peers. Work-related drug testing and anxieties about retaining employment and/or gaining access to children had encouraged people to stop, or at least significantly curtail, their drug and alcohol use. Employment also reduced financial incentives for re-offending, and many commented on the value of having a stable, predictable source of income.

While just under a third of this group had breached their release conditions, and an equivalent proportion had been charged with new offences, the ways in which these events were perceived was distinct. Re-offending was often characterised by this group as “a little hiccup” and seldom interrupted personal narratives of desistance. Despite new charges, therefore, people in this group still considered themselves to be in the process of desisting and becoming “legit”. Those “doing well” were optimistic and forward-focused: they had future goals and were taking active steps to achieve them. They believed that their futures were largely in their own hands.

Going OK

Those “going OK” were often preoccupied with fulfilling the conditions of their release. Many viewed being on release or parole conditions as placing them in some form of “holding pattern” in which they could not get on with their lives until the condition period expired. Living in limbo, many lacked direction and were unable to articulate what steps they would take to “get on” once sentence requirements were completed. This group contained a large proportion of women and those categorised as “low risk”. They had less exposure to imprisonment and over half were serving their first prison sentence at the time of the first interview. Most felt positively towards their probation officer and most had been highly compliant with their post-release conditions. Indeed, only 14% had breached their sentence conditions, the lowest rate for any outcome group. This group also had low levels of re-offending, with under one third facing new charges. This was a similar level to those “doing well”.

Despite being more likely to have left school with qualifications than other outcome categories, most had worked only intermittently throughout their lives, and almost 80% were unemployed prior to their arrival in prison. Over half of this group were receiving a benefit pre-prison (53%), with most receiving Job Seeker benefits. On release, most of these people had resumed benefit dependency and continued to be unemployed. People reported spending their days playing computer games, watching TV, engaging in social media, and undertaking domestic chores. While for some “not doing too much” was a conscious strategy to ensure they were not overwhelmed by competing demands, others reported “floating about” feeling bored, lonely, and depressed by the lack of constructive activity in their lives. Many were focused more on avoiding “bad influences” or situations than on doing “good” or meaningful things. Avoidance for some had become their dominant “activity”:

I am consciously aware of what I need to do just to keep out of trouble … stay away from the environment … staying out of trouble. Avoiding is one of the main things (Dave, Māori male in his 40s who had just completed his second prison sentence).

As part of their avoidance strategy, many within this group were successfully avoiding, or at least curtailing, drug and alcohol use.

People within this group typically saw release conditions as an impediment to employment. Many struggled to manage competing priorities post release, and while employment was considered important, it was not something they could seriously contemplate without other areas of their lives being resolved, such as sentence requirements, sustainable accommodation, access to children, and relationship problems. Employment assistance was, therefore, something they wanted “down the road” rather than immediately following their release from prison. For many, delays in accessing rehabilitation programmes caused conflicts between meeting sentence requirements and obtaining employment during the second half of the condition period when financial support from others was waning. A desire for independent accommodation was often a primary imperative for seeking employment at this point.

Many felt fatalistic about the impact of conviction histories on their employment prospects, yet had only vague notions of what occupations they might be excluded from. This was particularly salient for women, who assumed they were excluded from working in all caring roles post-conviction, despite this being their only previous work experience. Those in work tended to see their current employment as temporary and often endured variable work conditions. Many were receiving the minimum wage and/or were engaged in casual roles with variable working hours making it hard to plan financially. Few saw a future working in the same line of work. Collectively, these factors offset the more positive gains that those “doing well” derived from employment.

Those “going OK” often avoided thinking too much about the future, including in relation to re-offending/desistance. This group revealed considerable ambivalence about desistance, with many stating that re-offending was simply a matter of chance which was largely beyond their control. There was a widespread lack of agency or self-determination among this group.

Struggling

Those “struggling” were more criminally entrenched than their better faring counterparts, with over half having completed ten or more prison sentences. Half also reported having experienced mental health problems throughout their lives, most commonly Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder. An equivalent proportion reported having ongoing associations with gangs. Prior to arriving in prison, just over a quarter had been employed, while half the people in this group had never or rarely worked during their lifetime. Pre-release, this group was three times more likely than those “doing well” to lack substantive accommodation plans and expect little or no pro-social support on release.

Following release, six in ten were facing new charges, and a similar proportion had breached their release or parole conditions. A further 80% had returned to prison on at least one occasion since they had left prison, and a similar proportion lacked stable housing. Several had been homeless for at least some time since release. Few had accessed a benefit post-release, and while this was sometimes characterised as a conscious choice, others spoke of significant difficulties accessing benefits and the financial hardship engendered by lengthy delays. Few had worked and only one person was still in paid employment at the time of their second interview. Despite recognising the value of employment to “going straight”, employment was rarely a top priority for this group. Rather, obtaining some form of income, accommodation, and support were more pressing considerations. In terms of the latter, many within this group lacked good social support networks and tensions surrounding intimate relationships proved to be a common destabilising force. A number were negotiating Protection and/or Non-Association Orders on release, which, in turn, had contributed to accommodation problems, financial hardship, and re-offending. Many had resorted to drugs, alcohol, and offending as a means of coping with adverse circumstances. Several had also struggled to access psychiatric medication in the community, which had further undermined efforts to hold down employment and/or avoid re-offending.

Overall, these people were often living chaotic lives, enduring multiple and compounding problems. Few within this group articulated any real desire to desist from crime and most evidenced a distinct lack of agency around their offending. Few took responsibility for their offending, as they believed this was largely determined by external forces. In the words of one participant: “what will be will be”. Many lived day to day, and avoided making too many plans as “anything might happen tomorrow” which could jettison good intentions. A number spoke of being “stuck” in cycles of offending, which they felt powerless to extricate themselves from. Perhaps not surprisingly given this attitude, people routinely blamed prison staff and probation officers for “causing” re-offending because they had “failed” to provide the practical assistance released prisoners felt they required. A well-rehearsed axiom among this group was “they set us up to fail”. Such concerns typically arose within a context of considerable economic hardship. For those in this category who professed a desire to change, many felt that they lacked the practical means to do so and felt trapped in their criminal lifestyle, with little alternative but to rely on the support of anti-social friends, family/whänau, and, occasionally, gangs.

Where to from here? Some implications for service design and implementation

While a large number of implications arose from the research, three main areas for action are briefly discussed here.

Prisoners’ post-release needs are highly individualised, multi-faceted, interactive and dynamic: reintegration services need to be individually tailored

Some people exit prison with extensive employment histories, accommodation organised, and strong social support structures in place. These people need little assistance from reintegration services and often derive little practical benefit from education, training and employment options offered in prison. Others leave prison with little or no work experience, no source of income organised, no accommodation, untreated mental health problems, and little or no social support. While some people received assistance they didn’t require, some in desperate need of assistance and at high risk of re-offending received little. Consequently, it is important to target services to those who need them most and who have the greatest level of risk. This could involve further prioritising prisoners with limited employment and training histories when allocating work and training opportunities within and beyond prison, and focusing intensive reintegration services on those without accommodation and/or sound support structures in place prior to release.

Core foundations need to be in place before employment is viable

While participants generally concurred that employment could help prevent re-offending and was critical in achieving long-term desistance, employment only became viable once other foundations were in place, namely: stable and sustainable accommodation, social supports, healthy relationships, and good mental health and addiction management. Employment was therefore the main post-release priority for those who already had these foundations in place. The completion of sentence requirements, particularly post-release rehabilitation programmes, was a commonly cited impediment to employment. On this basis the primacy of employment assistance within initial post-release services should be reviewed, and the possibility of targeting additional employment assistance further “down the road” during the second half of the condition period considered. Towards this end, there is also merit in attempting to schedule rehabilitation programmes within the first half of the condition period to ensure programmes do not come into conflict with employment pressures emerging in the later part of the condition period.

More than any other factor, a lack of stable accommodation was the most critical contributor to negative post-release outcomes. There is a need for greater provision of emergency accommodation, as well as more support to help released prisoners transition from short-term accommodation to more stable medium-term housing. The conditions of existing accommodation options should also be reviewed to identify possible improvements. Since the completion of the research the department has commenced a number of initiatives to increase the provision of emergency accommodation for released prisoners. For example, it has increased the number of contracted places for supported accommodation from 703 places per annum to 903 places that provide up to three months’ transitional accommodation and, for a third of those places, placement into employment.

Release planning in prison should ensure people exit prison with concrete, realistic plans, necessary documentation in place, and adequate safety plans for managing family violence risk

Over half of participants could not articulate firm plans for what they planned to do once they left prison, sometimes within weeks of release. This was more likely to be the case for those serving long sentences compared to those serving short sentences, as the latter were more likely to have accommodation, social support and past job contacts in place leading up to release. While a reasonable proportion of people said they wished to study following their release, few could articulate what or where they planned to study, or how studying would assist them in terms of employment once they had completed it. Many spoke about being overwhelmed following their release with the sheer volume of issues they had to contend with, including setting up bank accounts and benefit payments, dealing with pre-existing fines and their debts, finding housing and employment, and negotiating child access arrangements, often while dealing with either protection or non-association orders. Those seeking employment expressed considerable anxiety about approaching new employers, and many worried about how potential employers would react when they disclosed their criminal convictions. People with mental health problems also spoke of the difficulties accessing medication. A number of people said they wanted someone to actively assist them to negotiate the myriad of demands they faced on release.

Informed by findings from the research, the Department of Corrections has launched a number of initiatives which aim to address these needs. For example, a Guided Release process recently introduced in New Zealand prisons involves case managers working intensively with prisoners being released from long sentences (two years or more) to develop detailed reintegration plans. In developing plans, case managers may accompany offenders into the community to help organise accommodation and employment opportunities. Similarly, Offender Recruitment Consultants (ORCs) were introduced in late 2016 to assist prisoners into employment. Eight consultants based at different locations throughout the country actively broker employment opportunities for offenders. Since its commencement in November 2016, over 420 offenders have been assisted into employment. On average they are placing about 70 offenders per month. To gain access to a greater number of job opportunities Corrections has also signed employer partnerships with 113 employers who have agreed to provide jobs to 1,087 offenders upon release. The department is also partnering with the Ministry of Social Development on the Supporting Offenders into Employment pilot. One aspect of the pilot involves dedicated case managers working with prisoners prior to release and up to 12 months post-release to obtain and maintain employment.

Finally, the research found that relationship and familial tensions often catalysed broader post-release adversity, such as loss of accommodation and failing to report. The provision of generic healthy relationship programmes to prisoners and/or released prisoners would likely contribute to improvements in other outcome indicators. More consistent screening for family violence issues pre-release, robust safety planning processes, and better community-based support would also help to alleviate some of the common tensions experienced by those returning to relationships or commencing new ones post-release. The Integrated Safety Response (ISR) initiative currently being piloted in Christchurch and the Waikato region has begun to address some of these issues for those deemed high risk.

References

Baldry, E. (2010) Women in transition: From prison to … Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 22(2): 254-267.

Davis. C., Bahr, S., Ward, C. (2012) The process of offender reintegration: Perceptions of what helps prisoners re-enter society, Criminology and Criminal Justice, 13 (4): 446-469.

Department of Corrections (2016) Department of Corrections’ Annual Report 2015-2016. Wellington: Department of Corrections.

Farrall, S. (2004) “Social capital and offender reintegration: making probation desistance focused’, In. S. Maruna and R. Immarigeon (eds). After Crime and Punishment: Pathways to Offender Reintegration. Devon, Cullompton: Willan, pp57-82.

Garland, B. and Wodahl, E. (2014) Coming to a crossroads: A critical look at the sustainability of the prisoner re-entry movement. In, M.S. Crow and J. O. Smykla (eds) Offender Reentry: Rethinking Criminology and Criminal Justice. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning, pp399-423.

King, S. (2013) Early desistance: A qualitative analysis of probationers’ transitions towards desistance, Punishment and Society, 15 (2), 147-165.

Maruna, S. (2001) Making Good: How Ex-Convicts Reform and Rebuild Their Lives. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Maruna, S. and Roy, K. (2007) Amputation or Reconstruction? Notes on the Concept of “Knifing Off” and Desistance From Crime. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 23 (1), 102-124.

Maruna, S. and Tosh, H. (2005) “The impact of imprisonment on the desistance process’, in J. Travis, and C.A. Visher (eds) Prisoner Reentry and Crime in America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp139-178.

Nugent, B. and Schinkel, M (2016) The pains of desistance, Criminology and Criminal Justice, 16 (5) 568-584.

Petersilia, J. (2003) When Prisoners Come Home: Parole and Prisoner Re-Entry. New York: Oxford University Press.

Piquero, A. R. (2004) Somewhere between persistence and desistance: the intermittency of criminal careers. In S. Maruna and R. Immarigeon (eds) After Crime and Punishment: Pathways to Offender Reintegration. Devon, Cullompton: Willan.

Visher, C.A., and Travis, J. (2003) Transitions from prison to community: Understanding individual pathways. Annual Review of Sociology, 29: 89-113.