Reconviction Rates of Sex Offenders: Five year follow-up study

Introduction

Prisoners serving sentences for sex offences make up around 20 percent of the New Zealand prison population on any given date. As a sub-group within the general offender population, sex offenders share a number of important characteristics. Awareness of those characteristics has relevance for understanding reconviction data of the type presented here. Firstly, victim surveys indicate that, of all crime types, sex offences are perhaps the least likely to result in the apprehension and conviction of an offender – it appears that the vast majority of offences are either not reported by victims, or not resolved by Police.[1]This means that conviction histories of sex offenders are often unrepresentative of actual offending behaviour. Second, it is widely recognised that sex offending can be a compulsive behaviour that persists over decades of an offender’s life. As a result there can be long time gaps between recorded criminal convictions; alternatively, offenders may still be active despite criminal records that suggest desistance. Thirdly, while “criminal versatility[2] " is the norm in the general offender population, many sex offenders have few, or only minor, convictions for other types of crime. Finally, in terms of impact, sex offences tend to be particularly harmful and damaging to victims.

Although a handful of recidivism studies about sex offenders have been conducted here and overseas, most have had small sample sizes. As a result, the reconviction patterns of this population are not particularly well-understood. Notwithstanding the points made above, many sex offenders are indeed reconvicted of new crimes, including crimes of both a sexual and non-sexual type.

The current study is intended to assist the Department of Corrections in meeting its strategic objectives regarding the management and rehabilitation of offenders. It provides straightforward data on the characteristics of sex offenders and their recidivism rates. The data presented here are based on the “recidivism index” (RI) methodology used in the Department of Corrections’ annual reporting of reconviction. This method quantifies the rate of reconviction and re-imprisonment for specified sub-groups of offenders, over follow-up periods of defined length, after release from a custodial sentence, or following commencement of a community sentence or order. Conviction and sentencing data is obtained from the Ministry of Justice’s Case Management System (CMS) database.

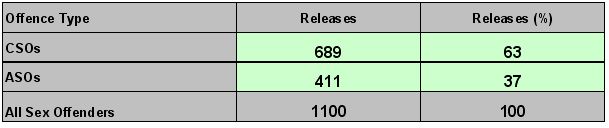

This report summarises patterns of reconviction and re-imprisonment of exactly 1100 male sex offenders who were released from prison during the 36-month period from 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2003. The conviction dataset included any reconviction for offences that occurred within 60 months of an individual offender’s release date (up to 31 December 2008)[3].

Reconviction figures reported here exclude convictions which result in sentences not administered by the Department (e.g., fine, convicted and discharged). The figures also exclude re-sentencing for breaches of community sentences, or recalls to prison for breaches of parole conditions. Similarly excluded are convictions relating to offences which pre-date the earlier sentence. In summary, all reconvictions data presented here should be interpreted as restricted to convictions for a new offence resulting in a community-based sentence or imprisonment.

Many offenders are sentenced to a prison term after being convicted of multiple individual charges. Under these circumstances, when offenders are grouped by offence type, the convention is to identify the “most serious offence” type[4] (MSO) for which they were imprisoned; this is based on the average number of days imprisonment imposed by judges for all instances of that specific offence type over the past five years. However, another way of identifying the offence type is according to an individual offender’s “lead offence”. This refers to the offence which incurred the greatest number of days of imprisonment imposed by the judge for that particular offender. It should be noted that in this study, offenders were included if they were originally imprisoned for a sex offence that was either the most serious offence or the lead offence. The former rule ensures inclusion, for example, of an offender convicted of robbery and sexual violation; the latter ensures inclusion of an offender convicted of multiple burglary and theft offences as well as a single indecent assault. However, both rules would exclude an offender who had been concurrently sentenced for rape and murder – such an individual would instead be classed as a “violent” offender.

This report also provides analysis by way of offenders’ characteristics such as age, ethnicity, offence type and previous criminal history. Recidivist offenders are the key challenge both to criminal justice sector agencies and to society at large. Therefore, analysis of the data includes a division of the population into two groups, “first-timers” and “recidivists”. A number of important findings emerge from this perspective on recidivist sex offenders.

For convenience purposes, throughout this report those convicted of sex offences against children (child sex offenders) are designated “CSOs”, while those convicted of sex offences against adult victims are designated “ASOs”. Offenders are categorised by the most serious offence for which they were originally sentenced.

It is important to note that countries differ markedly in how criminal justice data are handled: reconviction and re-imprisonment rates are influenced by legislation, sentencing practices, resource levels of criminal justice sector agencies, as well as volumes of crimes committed and rates of detection and resolution. Consequently, comparison of reconviction or re-imprisonment rates between countries is a fraught exercise. Nevertheless, the study provides a benchmark for five-year recidivism rates for male sex offenders released from New Zealand prisons. It is hoped that the study, along with the others in the same series[5]will be a valuable reference tool for those interested in correctional trends and issues, and will inform discussions on improving New Zealand’s correctional system.

Characteristics of the sex offenders

Of the 1100 offenders imprisoned for sex offences between January 2001 and December 2003, 63 percent were imprisoned for sex offences against children (CSOs) and 37 percent were imprisoned for sex offences against adult victims (ASOs).

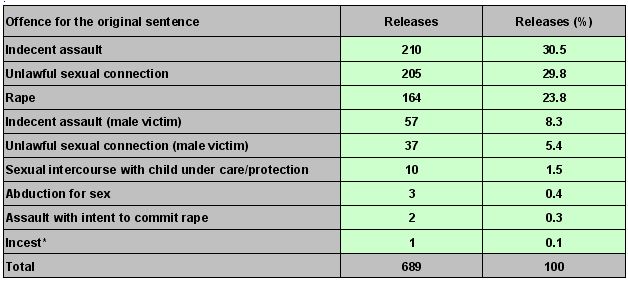

Offence breakdown

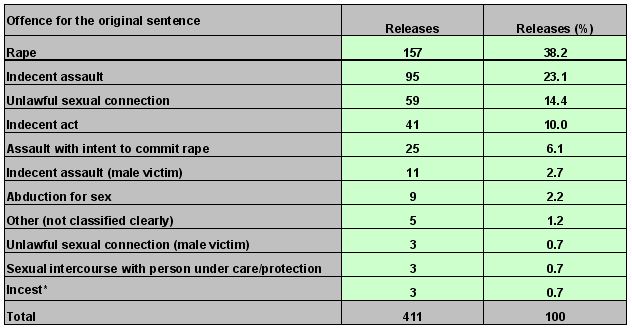

The below table shows the specific offences by ASOs. Of the 411 offenders originally imprisoned for sex offences against adult victims, the highest proportion were imprisoned for rape (38%), followed by indecent assault (23%) and unlawful sexual connection (14%). As with sex offences against children, these three offences make up about 76 percent of all sex offences committed against adult victims.

Offence types of sex offenders against adult victims

* The very low numbers of offenders convicted of Incest are not representative of the volume of offenders whose offences were of an intra-familial nature; in most cases of this nature, Police will have brought offence charges of other types, such as those higher in the lists above.

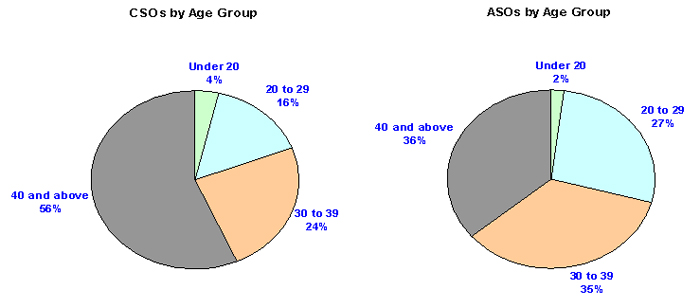

Age distribution

On average, sex offenders generally are older than offenders who commit other types of crime, and CSOs tend to be older than ASOs. The median age of CSOs is 41 years and the median age of ASOs is 35. In contrast, the median age of burglars is 24 years. It is important to note here that the time elapsed between actual offence date and conviction date is often much longer for sex offenders compared to burglars. The graphs below show the age distribution of both CSOs and ASOs. About 56 percent of CSOs were 40 and above at the time of release, but only 36 percent of ASOs were 40 and above.

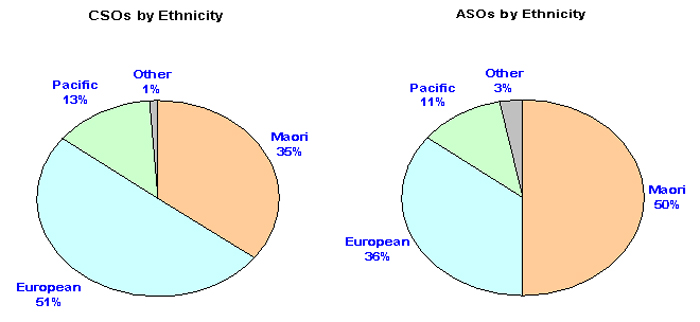

Ethnicity

About 50 percent of the general prisoner population in New Zealand are Maori. The graphs below show the ethnic breakdown for both ASOs and CSOs. Interestingly, about half of ASOs were Maori, while only a third of CSOs were Maori.

Criminal history

As already noted, imprisoned sex offenders tend to have fewer previous convictions for other types of offending, although a proportion do have prior convictions for sex offences. The former is particularly true for CSOs: of the 689 CSOs in the sample, 225 were previously imprisoned for any offence and 60 for sex offences against children. In terms of criminal convictions (which may or may not have resulted in imprisonment) of the 689, 98 were previously convicted for sex offences against children and 36 were convicted for sex offences against adult victims.

Criminal versatility is more apparent amongst ASOs. Of the 411 ASOs, 208 were previously imprisoned for any offence and 53 for sex offences against adult victims. Of these 411 offenders, 86 were previously convicted for sex offences against adult victims and 25 were convicted for sex offences against children.

Overall recidivism rates of sex offenders (60-month follow-up)

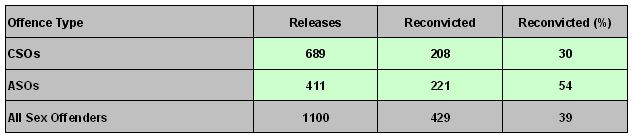

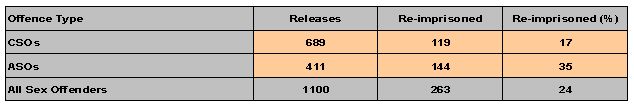

Of the 1100 sex offenders released from prison between 1 January 2001 and 31 December 2003, 39 percent were subsequently convicted of a new offence and were either returned to prison or commenced a community sentence at least once during the 60-months follow-up period. The reconviction rate of ASOs (54%) is significantly higher than that of CSOs (30%). The re-imprisonment rate for all released prisoners within five years is 52%[6]. Notes that these figures relate to reconvictions for any type of offending, not solely sexual re-offending.

In terms of the more serious re-offending, across the entire sample, 24 percent were convicted of a new offence and were returned to prison at least once during the

60-months follow-up period. The re-imprisonment rate of ASOs (35%) was twice that of CSOs (17%).

The differences found between CSOs and ASOs are likely to be a reflection of a number of variables. CSOs tend to be older than ASOs. Further, as already noted, criminal versatility – the tendency to commit offences across multiple classes of offence type - is more commonly observed amongst ASOs. It is possible also that reconviction rates are lower because sex offences involving child victims have a lower overall probability of being reported and an offender successfully apprehended and charged

Once again, it is important to note that these figures also exclude re-sentences for breaches of community sentences or recalls to prison for breaches of parole conditions.

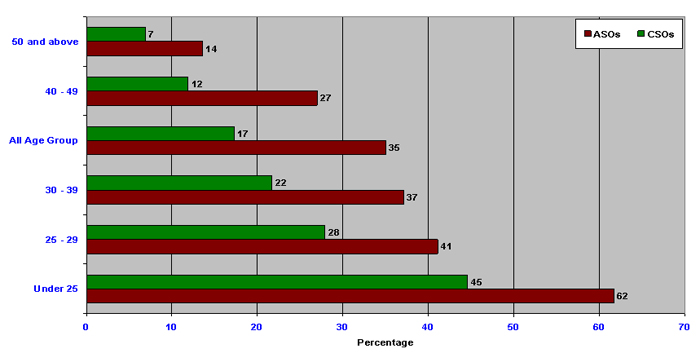

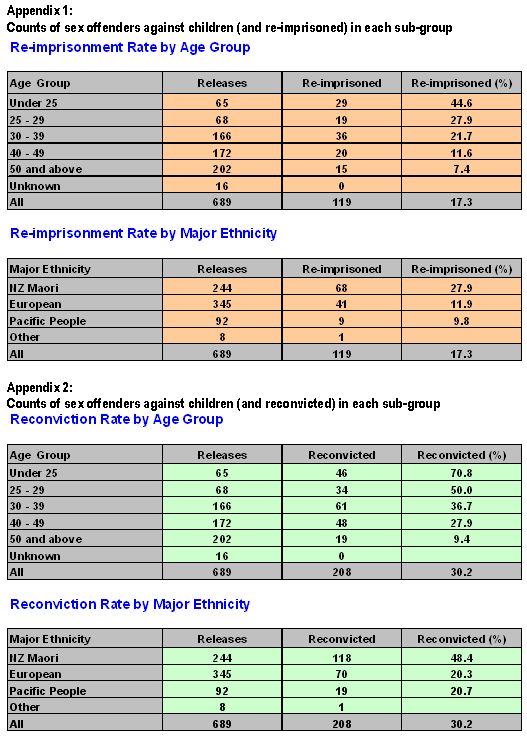

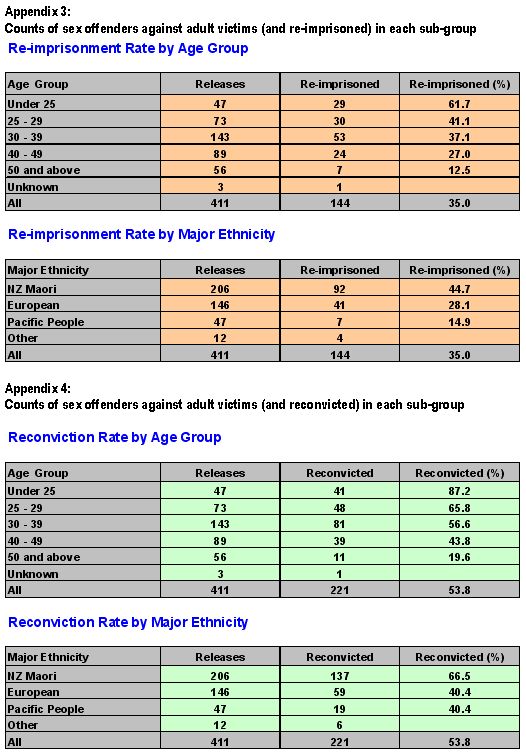

Re-imprisonment rates by age at release

The relationship between age and reconviction rates has been the subject of considerable criminological analysis in the past. A great many studies have established a very strong (inverse) correlation between age and recidivism rates for offenders of any offence sub-type.This current analysis also explores the relationship between age and re-imprisonment rates for sex offenders. The graph below gives rates of re-imprisonment for offenders of different age bands (note that prisoners’ ages here are as at time of release). Sixty two percent of ASOs aged under 25 were re-imprisoned within 60 months, while just 14 percent of those aged over 50 were re-imprisoned. Similarly, 45 percent of CSOs aged under 25 were re-imprisoned within 60 months, while just seven percent of those aged over 50 were re-imprisoned.

Graph 5: Re-imprisionment rate of sex offenders (for any offence) by age at release

Clearly, for those aged under 25, reimprisonment rates of ASOs (62%) and of CSOs (45%) are very high, similar to the rates observed with prisoners sentenced for other offence types. In other words, the overall observation that sex offenders have relatively low reconviction rates does not apply amongst sex offenders aged under 25. Note again that these figures relate to reconvictions for any type of offending, not simply sexual re-offending.

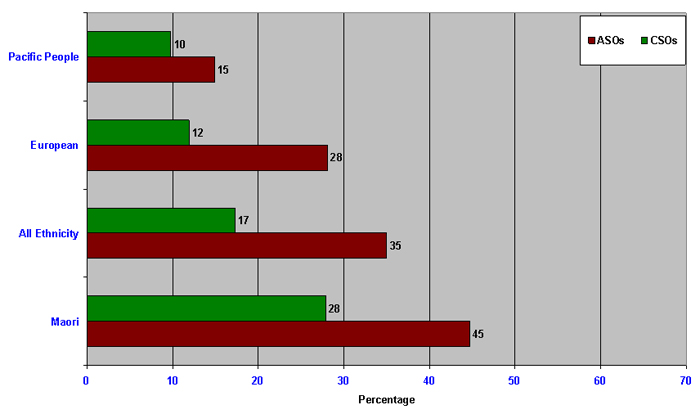

Re-imprisonment rates by ethnicity

For Maori CSOs, their re-imprisonment rate over 60 months (28%) is considerably higher than the rate for either NZ Europeans (12%) or Pacific offenders (10%). This difference is likely to be a reflection of a number of variables. Higher rates of

re-offending are observed generally amongst Maori, not just in this area. Maori offenders as a group tend on average to be younger than non-Maori offenders. For example, the median age of Maori CSOs is 38 compared to 43 for non-Maori CSOs.

Graph 6: Re-imprisonment rate of sex offenders (for any offence) by ethnicity

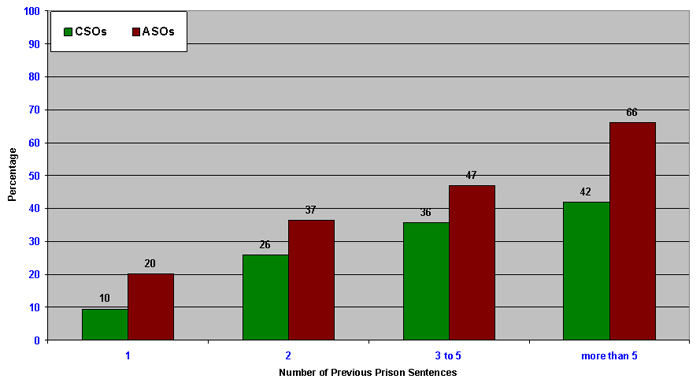

Re-imprisonment rates by number of previous sentences

The following graph indicates the relationship between re-imprisonment rates and the number of previous custodial sentences served. Only 10 percent of CSOs released from their first term of imprisonment were re-imprisoned by the end of the 60 months. In marked contrast however, 42 percent of those who had served more than five prison sentences were re-imprisoned. Similarly, 20 percent of ASOs released from their first term were re-imprisoned, compared to 66 percent of those who had served more than five prison sentences.

These figures confirm the well-recognised pattern that, the more time in the past someone has been in prison, the more likely they are to return to prison following any given release.

Graph 7: Re-imprisonment rates by number of previous prison sentences

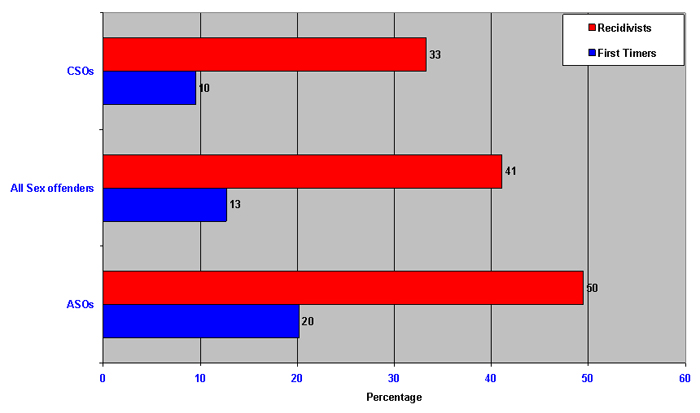

Re-imprisonment rates: “First-timers and “Recidivists”

The following section examines more closely the reconviction dataset by grouping offenders according to the number of previous prison terms into two sub-sets. Those for whom their release between 1 January 2001 and 31 December 2003 was from their first-ever prison term are designated in the following as “first-timers”. The remainder, who had served two or more previous prison terms, are designated as “recidivists”.

Of the 689 CSOs, about two thirds were in prison for the first time. The

re-imprisonment rate of these first-timers is 10 percent; in contrast, the re-imprisonment rate of the remainder – the recidivists - is 33 percent. The reconviction rate of the first-timers is 19 percent and the recidivists is 54 percent.

Of the 411 ASOs, about half of them were in prison for the first time. The

re-imprisonment rate of these first-timers is 20 percent; in contrast, the re-imprisonment rate of the remainder – the recidivists - is 50 percent. The reconviction rate of the

first-timers is 37 percent and the recidivists is 70 percent.

Graph 8: Re-imprisonment rate by offence type: First-timers vs Recidivists

In general, reconviction and re-imprisonment rates for CSOs are low relative to other offence types. However, when disaggregated by previous sentences, this finding does not hold true for the recidivist CSOs who are thus 3.3 times more likely to return to prison than first-timer CSOs. Similarly, recidivist ASOs are 2.5 times more likely to return to prison than first-timer ASOs.

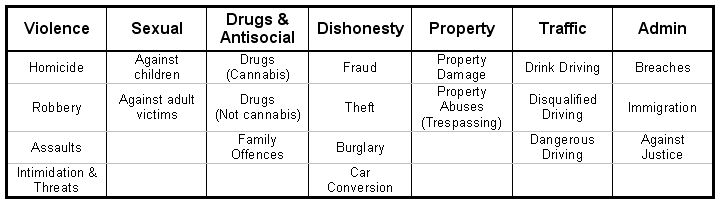

Correlations between original offence group and re-offence group

Also analysed for the purposes of this report was the nature of offence for which offenders in the sample were reconvicted. For this discussion, it is important to distinguish between offence group and offence type. The offence group is the broad category of crimes encompassing many different offence types. For example, the dishonesty offence group comprises a variety of offence types, such as burglary, theft, fraud, and car conversion (see the table below for these groupings). The sex offence group is comprised almost entirely of offences against children and adult victims, although a small number of offences do not involve direct affronts to another person (e.g., bestiality, pornography-related offences).

Offence groups and major in component offence types

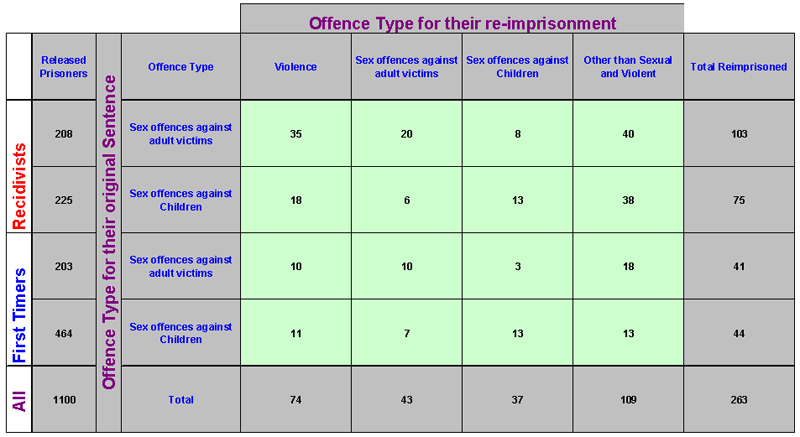

Research indicates that some offenders are persistently re-imprisoned for the same offence type; many drink- drivers and burglars display this tendency. However, the majority of offenders are imprisoned and re-imprisoned for a range of offences types. The table on the next page represents the correlation between original offence type and the re-offence type for the current sample. This section also examines the offence type and the re-offence type more closely by “first-timers” and “recidivists” sex offender populations.

- of the 464 first-timer CSOs, 44 were re-imprisoned for any conviction within 60 months; of the 44, only 13 were re-imprisoned for the same offence type.

- of the 225 recidivist CSOs, 75 were re-imprisoned for any conviction within 60 months; of these, 13 were re-imprisoned for the same offence type.

- of the 203 first-timer ASOs, 41 were re-imprisoned for any conviction within 60 months; of these, 10 were re-imprisoned for the same offence type.

- of the 208 recidivist ASOs, 103 were re-imprisoned for any conviction within 60 months; of these, 20 were re-imprisoned for the same offence type

It is apparent from inspection of the table below that relatively few imprisoned sex offenders are reconvicted for new sex offences within five years of release. In fact, convictions for new violent offences are as equally likely to occur as are convictions for sex offences. However, if reconviction does occur it is almost as likely to be for offences other than sex or violent offending. Thus criminal versatility (an absence of offence type specialisation) appears not be to uncommon within the sex offender population. This is particularly the case with the re-offence of recidivist sex offenders, whose next offence appears to be more likely a non-sexual offence.

Table: Released six offenders by offence type for the original sentence vs offence type for the re-imprisonment (60 months follow-up)

As was noted in the Introduction, sex offences are subject to extensive under-reporting and, even when reported, significant attrition of cases occurs at every subsequent stage (identification and apprehension of the offender, charging of the offender, conviction of charged offenders). The possibility therefore cannot be dismissed that, amongst CSOs particularly, that a significant proportion are indeed “specialist” offenders for that type of offence, but that their criminal history simply fails to reflect the true extent of their crimes.

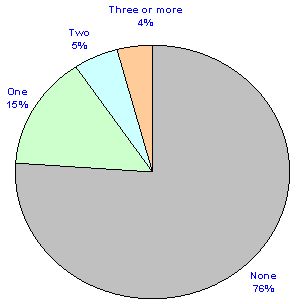

Frequency of re-imprisonments (60-month follow-up)

A final perspective on the population studied here is the number of imprisonments experienced by individual offenders during that 60-month follow-up period. A proportion of the sample were found to have recorded more than one term of imprisonment.[7] As noted above, across the entire sample of offenders (n = 1100), 24 percent (n = 263) were convicted of a new offence and were returned to prison at least once during the 60-month follow-up period. These re-imprisoned offenders accumulated a total of 484 sentences of imprisonments for new offences over the 60 month period. Forty five offenders released in the same period were convicted of a new offence and returned to prison at least three times during the 60-month follow-up period.

The graph below shows the frequency of re-imprisonments of all sex offenders released during the 36 month period from 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2003.

Graph 9: Frequency of re-imprisonments, all sex offenders

Summary

Of all male sex offenders released from New Zealand prisons between 1 January 2001 and 31 December 2003, 24 percent were convicted of a new offence and returned to prison at least once in five years. For the same population, the reconviction rate over five years was 39 percent.

A number of interesting findings emerge from the data:

- within the broad category of “sex offenders” released from prison each year, around two thirds were serving sentences for offences against children, and one third for offences against adults.

- in both sub-groups, around 80% were sentenced for either rape, indecent assault or unlawful sexual connection offences

- child sex offenders (CSOs) tend to be somewhat older than sex offenders against adults (ASOs), whose average age more closely resembles that of other offenders

- the level of over-representation amongst Maori found in most sub-groups of imprisoned offenders is evident amongst ASOs, but markedly less so amongst CSOs

- both reconviction and re-imprisonment rates amongst ASOs are high when compared to CSOs

- the study confirms the strong (inverse) correlation between age and recidivism rates of CSOs and ASOs, with surprisingly high rates of re-imprisonment amongst young (< 25 years) sex offenders

- rates of reconviction or re-imprisonment specifically for new sex offences amongst the sex offender population are relatively low: just over 5% of CSOs were reimprisoned for a subsequent sex offence, as were 10% of ASOs

- even amongst recidivist sex offenders, there is only a modest tendency towards offence specialisation; in general any subsequent offence of an offender previously imprisoned for a sex offence is as likely to be a violent offence than it is a sex offence, and is more likely in fact to be of a different type entirely.

- when sex offenders are sub-grouped according to whether there has been a previous imprisonment, a sub-set of offenders emerge who appear to be active criminals for whom sex offending is just one expression of their general anti–social lifestyles; it thus emerges that a proportion of sex offenders are more versatile in their criminal careers than is generally assumed

All of the foregoing must be interpreted with due consideration of the dynamics involved in criminal convictions for sex offences. In particular, this type of offending is subject to low rates of reporting by victims. Even when reported, other processes combine to severely reduce the proportion of reported cases which eventually result in an apprehended offenders being subsequently convicted and sentenced for the offence. Consequently, conviction data for sex offences should never be interpreted as an accurate indication of incidence of offending and reoffending by sex offenders.

[1] Data on sex offence victim reporting in New Zealand can be obtained in the latest (2009) crime victims survey, available at https://www.justice.govt.nz/justice-sector-policy/research-data/nzcvs/nzcass/

[2] Criminal versatility refers to the tendency for offenders to commit crimes across the range of categories such as violence, dishonesty, traffic offending and drugs.

[3] The data set also included reconvictions on dates up to 31 December 2009 when the offence date was prior to 31 December 2008.

[4] MSO rankings are calculated by Ministry of Justice.

[5] Reconviction Patterns of Released Prisoners (A 60-months Follow-up Analysis), available at http://www.corrections.govt.nz/research/reconviction-patterns-of-released-prisoners-a-60-months-follow-up-analysis2.html

[6] Reconviction Patterns of Released Prisoners (A 60-months Follow-up Analysis), available at http://www.corrections.govt.nz/research/reconviction-patterns-of-released-prisoners-a-60-months-follow-up-analysis2.html

[7] The figures reported below count distinct “aggregate sentences” for each released prisoner during the 60-month follow-up period. An aggregate sentence of imprisonment reflects the fact that many offenders are sent to prison after being convicted for multiple charges, each of which attracts a separate sentence of imprisonment (sometimes of varying lengths). Counting aggregate sentences however can underestimate the frequency of imprisonments, as some prisoners are convicted and sentenced to a further term of imprisonment while already a sentenced prisoner (the second sentence may be simply incorporated into the existing aggregate sentence).