Psychopathy and its implication for criminal justice - Key presentations and discussions from a specialist conference held May 2015, Austin, Texas.

Dr Nick J Wilson

Principal Adviser, Psychological Research, Office of the Chief Psychologist, Department of Corrections

Author biography:

Dr Nick Wilson has been with the Department for 19 years. Nick began employment with Corrections as a clinical psychologist in Hamilton until 2001 when he became a specialist psychological researcher. He has been involved in research into the assessment and treatment of high risk offenders including psychopaths for many years. His PhD thesis was on the use of psychopathy in predicting serious re-offending by those released on parole and he has recently been involved in creating the High Risk Personality Programme. Nick is currently part of the team led by the Chief Psychologist.

Introduction

The author attended the ‘Without Conscience: Psychopathy and its Implications for Criminal Justice and Mental Health’ conference in May 2015 along with a two day pre-conference workshop on the assessment of psychopathy delivered by Dr Robert Hare. Dr Hare is the developer of the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R), which is used worldwide to assess this severe personality disorder associated with higher risk of serious offending. The Psychopathy Checklist: Screening Version (PCL: SV) developed by Dr Hare is one of the specialist assessment tools used by Corrections psychologists as part of risk assessments carried out here in New Zealand. Attendance at the workshop conducted by Dr Hare and Dr Matt Logan confirmed the training approach taken in New Zealand, and the author was invited to assist in delivering part of the training, especially in regards to the treatment of psychopathy. Recent research presented in the psychopathy assessment workshop, along with information gained from discussions with the presenters, have been incorporated into the New Zealand psychopathy training workshops undertaken by the author. In addition to the continued endorsement of the training approach taken by New Zealand Corrections, Dr Hare and the other invited speakers at the conference made reference to the cutting edge efforts to treat psychopathic offenders in the department’s High Risk Personality Programme. The following information is based on the conference presentations by the event’s invited speakers as well as discussions held by the author with the presenters.

Psychopathy profiles by Professor Robert Hare

Dr Hare is Emeritus Professor of Psychology, University of British Columbia, where he has taught and conducted research for more than four decades. He has devoted most of his academic career to the investigation of psychopathy, its nature, assessment, and implications for mental health and criminal justice. He is the author of several books and more than one hundred scientific articles on psychopathy, and the developer of the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R) considered the gold standard for the assessment of psychopathy.

In his address to the conference, Dr Hare spoke about recent developments that involved a major focus on variable and person-centred applications of the four sub-factor model of psychopathy. In particular, that the discovery of subtypes may help us to understand differing expressions of psychopathy and the roles played by psychopathy in a wide array of disciplines and contexts important to society.

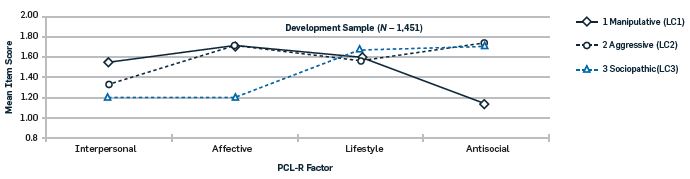

These differing score profiles were based on the establishment of four sub-factors in the PCL-R (Interpersonal; Affective; Lifestyle; and Antisocial) (Neumann, Hare, & Newman, 2007). Recent research found three subtypes emerged that, while similar in terms of overall PCL-R scores, were separate when their sub-factor scores were plotted (Mokros et al., 2015). Tentative labels assigned to the subtypes (see Figure 1) were Manipulative psychopaths (LC1), Aggressive psychopaths (LC2), and Sociopathic offenders (LC3).

Dr Hare spoke about how the differences in the subtype were reflected in differences in offending. The manipulative psychopath (high on interpersonal, affective and lifestyle deficits but low on antisocial) were high on fetishism and deviant sexual behaviour and fraud offending. The aggressive psychopath (moderate scores interpersonal, high scores for affective lifestyle and antisocial deficits) had high rates of instrumental violence that functioned to manipulate and solve problems for them. The third subtype, sociopathic psychopath (low interpersonal and affective, but high manipulation and antisocial) was viewed as more capable with normal emotions; hardcore criminals but lower on manipulation. The sociopathic psychopath therefore, while displaying many psychopathic features, has a capacity for affect, guilt, and remorse at least on a par with the average offender. While both the aggressive and the sociopathic psychopaths are high on antisocial acts and likely have equal risk of re-offending, the sociopathic psychopath may be more treatable or externally managed on probation.

While the research into the psychopathic subtypes is recent it does have implications for the work of Corrections in New Zealand. The differing styles will assist in informing specialist risk assessments by department psychologists, as well as in assessing the effectiveness of treatment for each subtype. While no formal analysis has been carried out with the department’s High Risk Personality Programme using the subtypes, the author’s clinical judgement is that numbers of both the aggressive and sociopathic psychopaths are being treated in this initiative. In terms of the manipulative psychopath, these offenders typically present in sex offender treatment or as those with single or isolated serious violence such as murder that are viewed as lower risk, but they may indeed have significant barriers to successful treatment from their high interpersonal and affective deficits.

Use of psychopathy in profiling by law enforcement by Dr Mary Ellen O’Toole

Dr O’Toole was a supervisory special agent with the FBI, working for more than 28 years as an agent, half of this time at the Behavioural Analysis Unit at Quantico, Virginia. Her work with the FBI involved her in using information from crime scenes in profiling and identifying the offenders. Dr O’Toole was involved in a number of high profile cases such as the ‘Green River Killer’, Ted Kaczynski, the ‘Unabomber’, the ‘Zodiac’ serial murderer, and the ‘Toy Box’ murder. She is recognised as the FBI’s leading expert in the area of psychopathy (O’Toole, 1999) and it is rumoured formed the model for one of the leading characters in the TV show ‘Criminal Minds’ based on the Behavioural Analysis Unit.

Her presentation at the conference was on how knowledge of psychopathy and different psychopathic presentations were an important consideration in identifying offenders and in predicting the type of crimes they may carry out if they re-offend (O’Toole, 2007). The appearance of normality by many psychopaths provides an understanding of their ability to access victims and avoid detection, in her words to “get under the radar”. An example Dr O’Toole provided was an interview with someone who knew Gary Ridgeway the Green River Killer, “He’s my next door neighbour. He says hello to me every morning when he walks his dog. He couldn’t be the serial killer. I would have noticed something different or strange about him”.

Psychopaths are also typically risk takers so boredom is a big turn off for them; this helps us to understand slips in behaviour, as well as their withdrawal from offending for periods. A lack of defensive injuries by victims was also viewed as significant when psychopathic glibness and superficial charm are considered, especially for repeat offenders who did not have prior knowledge of their victims. Dr O’Toole spoke of her experience with the ‘Toy Box’ murderer, David Parker Ray, a sexual sadist suspected of murdering as many as 60 people from Arizona and New Mexico. David Ray had spent $100,000 creating a soundproofed 20 foot truck trailer and equipped this with items used for torture, including a gynaecological examination table. Dr O’Toole described David Ray as extremely well spoken and educated, and charming and courteous when interviewed by her, although she said this may all have changed if he had her in his torture chamber!

Dr O’Toole also spoke about aspects of disposal of the body at the crime scene such as by Gary Ridgeway the ‘Green River Killer’ where disposal of remains in a disrespectful/degrading manner suggests the killer sees victims as non-human/objects. The examples provided were of bodies posed to cause an impact on those finding the remains and to demonstrate the total power of the offender. Psychopathy and low level of anxiety meant crimes could be carried out under the nose of the police, or, if detected, the offender was able to readily explain their presence. In some cases this meant the offender stayed to help the police search for the victim or were so mission focused or persistent they stuck around at the crime scene or attended the funeral.

In summary, Dr O’Toole emphasised that four traits from the psychopathic construct assisted the analysis of violent crime scenes; impulsivity, sensation-seeking, glib and superficial charm, and conning and manipulation. With psychopathic offenders viewed as a tremendous challenge for law enforcement professionals, analysis of violent crime scenes that is based on the traits, characteristics, and behaviours of psychopathy is regarded by Dr O’Toole as a tremendous law enforcement tool.

In New Zealand Corrections, using the information about the crime can assist department psychologists in considering the role that psychopathy may have played in the offending and in determining the risk of re-offending. It is also useful in the generation of viable risk scenarios that can be used to better manage psychopathic offenders released on parole.

Psychopathy and its association with attacks on law enforcement officers by Dr Matt Logan

Dr Matt Logan completed his PhD at the University of British Columbia while he was an active police officer. He was a member of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) for 28 years serving in five communities within British Columbia, and a tour of duty in Ottawa and at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center (FLETC) in Glynco, Georgia. Dr Logan retired from the RCMP in 2009 and now provides forensic behavioural consultation and training for law enforcement and criminal justice officials.

Dr Logan presented on his work on identifying those who attack and often kill law enforcement personnel. He spoke of how threats to criminal justice officials have increased markedly since 2009 in the USA. Dr Logan said that analysis of lethal attacks on police indicated that 45% of those he called ‘cop killers’ were psychopaths, with 28% on judicial oversight where they knew they were going down for a crime and so decided to take someone with them. In discussions with the author, Dr Logan confirmed that while his presentation was focused on police personnel he equally viewed the information as applicable to attacks on Corrections staff.

Dr Logan began his presentation by talking about an incident on March 3, 2005 in Mayerthorpe, Alberta in which four RCMP officers were killed in the line of duty. They were ambushed and shot to death in cold-blood by a known criminal described by members of the community as dangerous and reclusive. Dr Logan believes this massacre, as well as other attacks on police, might have been prevented had the police been thoroughly briefed on the risk posed by this type of killer. His analysis of the killer in the Mayerthorpe case, James Roszko, indicated the motivating mind-set was revenge but the prominent personality was psychopathic.

In general, Dr Logan believes that perpetrators of violence against law enforcement and other authority figures fit into one or more of the following categories:

- The Revenge Oriented Mind (typical for some perceived indignation)

- The Psychopathic Mind (lack of remorse, empathy, grandiose etc)

- The Delusional Mind (persecutory, paranoid usually)

- The Mind with Over-Valued Ideas (an unreasonable belief over which the person has become obsessed).

Dr Logan stated that it is not necessarily big city gang members, the Hells Angels, or the Mafia that is killing criminal justice officials, instead it is the psychopath in society. The psychopath might be a member of the Mafia, Hells Angels, or the Bloods but it is not the gang affiliation that was the common factor, it was the psychopathic personality (Hare & Logan, 2007). He acknowledged that not every psychopath is a murderer but it is often the psychopath with other behavioural and contextual factors (i.e. perceived loss, revenge orientation, increased negative contact with law enforcement) that creates a perfect storm and catches law enforcement personnel in the maelstrom. Usually the ‘cop killer’ was a ‘lone wolf killer’ with such lone individuals being far more successful in their attacks (Logan, 2014).

Dr Logan, based on his analysis of the research, found people who’d killed law enforcement officers had similar features. Similarities included previous violence, early violence, threat or aggression toward authority, perceived loss of freedom, previous use of weapons in violent acts, and personality disorder with psychopathic features. Dr Logan said that he was not ignoring the violence risk posed by gang membership and the risk it poses to law enforcement safety but in his opinion, it is the revenge-oriented, ‘nothing more to lose’ psychopath that will be our greatest danger.

While lethal attacks on New Zealand Corrections staff have thankfully been rare, if one considers serious assaults and wounding then the number is far greater. The research by Dr Logan and others looking into attacks on law enforcement personnel may well provide some guidance in how to better understand which offenders are more likely to attack staff, especially those with psychopathic and revenge seeking characteristics.

Dr Steve Porter and Dr Woodworth

Dr Stephen Porter received his Ph.D. in forensic psychology at the University of British Columbia and is a researcher and consultant in the area of psychology and law. After working as a prison psychologist, Dr Porter spent a decade as a professor at Dalhousie. In 2009, he transferred to the University of British Columbia, where he assumed a position as a professor of psychology and the Director of the Centre for the Advancement of Psychological Science & Law (CAPSL). Dr Porter has published numerous scholarly articles on psychopathy and violent behavior, deception detection, and forensic aspects of memory.

Dr Michael Woodworth works closely with Dr Porter and is a professor at the University of British Columbia. He received his Doctor of Philosophy in 2004 from Dalhousie University. His primary areas of research include psychopathy, criminal behavior, and deception detection.

Dr Porter spoke about his research into the language of psychopathic offenders using computerised text analysis that uncovered the word patterns of predators. This research found that the words of psychopathic murderers matched their personalities, which reflected selfishness, detachment from their crimes and emotional flatness (Hancock, Woodworth, & Porter, 2013). This research found that psychopathic speech reflected an instrumental/predatory world view, unique socio-emotional needs, and a poverty of affect.

Computerised text analysis shows that psychopathic killers make identifiable word choices beyond conscious control when talking about their crimes. Psychopaths used more conjunctions like ‘because’, ‘since’ or ‘so that’, implying that the crime ‘had to be done’ to obtain a particular goal. Dr Porter stated they also used twice as many words relating to physical needs, such as food (details on what they had to eat on the day!), sex or money, while non-psychopaths used more words about social needs, including family, religion and spirituality. Psychopaths were more likely to use the past tense, suggesting a detachment from their crimes. Finally they were found to be less fluent in their speech, using more ‘ums’ and ‘uhs’. Dr Porter speculated that the psychopath is trying harder to make a positive impression, needing to use more mental effort hence the less than fluent speech.

Dr Porter also highlighted other research he had been involved in where an attempt was made to answer the question ‘Do psychopathic individuals have the ability to detect useful and/or vulnerable victims?’ (Wilson, Demetrioff, & Porter, 2008). This study used a non-forensic sample of males who participated in a social memory experiment. The study involved the recognition of faces and the recall of the biographical details of artificially created characters differing in their relative career success and emotional vulnerability. Participants were shown pictures of equally attractive women that had differing biographic details. High-psychopathy participants had near-perfect recognition (90%) for sad, unsuccessful female characters, but impaired memory for other characters. Yet they had no special memory ability, rather, they prioritise recall of potential victims.

The findings suggest that psychopathic personality is associated with ‘predatory memory’ even in the absence of overt criminality.

Dr Woodworth continued the theme started by Dr Porter by discussing his research into the language of psychopaths. He spoke about genuine pleader language using ‘we rather than I’ and use of temporal words such as days and weeks. In contrast, liars used fewer words, more tentative words, tended to ramble, were less coherent, and said words such as ‘they, anybody, somebody, and just’ in describing their crimes. The psychopathic offender was likely to reinvent their crime as reactive rather than instrumental and they portrayed themselves as less culpable and personally involved. Dr Woodworth spoke about how computerised linguistic analysis programmes had transformed our ability to pick liars; in his words you “can’t beat the computer”.

Dr Woodworth talked about his recent research into how extended contact with a psychopath leads to less accurate perceptions about their behaviour, an important consideration when one considers the judgement of those treating or closely managing offenders. He described that it was face to face contact that provided psychopaths with the greatest ability to manipulate; they needed to have their eyes on you. In a task involving selling a product, psychopaths were actually less successful than non-psychopaths when they could only communicate via email text rather than in a Skype call.

The research presented by both Dr Porter and Dr Woodworth clearly has relevance to the work of Corrections staff in New Zealand in effectively managing and assessing the risk of offenders with psychopathic traits. This relevance could include ensuring that vulnerable staff do not become the prey of psychopathic offenders through better monitoring as well as ensuring that those in close contact do not make key risk management decisions. There may also be value in investigating whether computerised linguistic analysis could assist our psychologists in understanding the word patterns revealed by offenders during psychological interviews.

References

Hancock, J. T., Woodworth, M. T., & Porter, S. (2013), Hungry like the wolf: A word-pattern analysis of the language of psychopaths. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 18, 102-114.

Hare, R.D., & Logan, M.H. (2007). Introducing Psychopathy to Policing. In M. St-Yves & M. Tanguay (eds). Psychologie de l’enquête: Analyse du comportement et recherche de la vérité. [The psychology of criminal investigation]. 563-645. Quebec : Editions Yvon Blais.

Logan, M. H. (2014). Lone wolf killers: A perspective on overvalued ideas. Violence Gender. 1, 159–160.

Mokros, A., Hare, R. D., Neumann, C. S., Santtila, P., Habermeyer, E., & Nitschke, J. (2015). Variants of psychopathy in adult male offenders: A latent profile analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. doi: 10.1037/abn0000042

Neumann, C. S., Hare, R. D., & Newman, J. P. (2007). The super-ordinate nature of the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised. Journal of Personality Disorders, 21, 102-117. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.2.102

O’Toole, M. E. (1999). Criminal profiling: The FBI uses criminal investigative analysis to solve crimes. Corrections Magazine,61.,4446.

O’Toole, M. E. (2007).Psychopathy as a behaviour classification system for violent and serial crime scenes. In H. Herve,& J. C. Yuille (Eds.), ‘l’he Psychopath: Theory, Research, and Practice (pp.30l-325). Mahwah, N J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Wilson, K., Demetrioff, J., & Porter, S.(2008). Journal of Research in Personality, 42,6