Alcohol and other drug testing trial of community-based offenders

Nyree Lewis

Senior Practice Adviser, Chief Probation Officer’s Team, Department of Corrections

Author biography:

Nyree joined the Department of Corrections in 2010 as a probation officer. Since then she has been a practice leader and is now a Senior Practice Adviser in the Chief Probation Officer’s Team. Nyree has a passion for probation practice and uses her experience in the field to help continuous improvement in this area.

Background

Testing for alcohol and other drugs (AOD) in the community enables Corrections and Police to intervene with offenders/bailees who are subject to an abstinence condition imposed by the courts or the Parole Board, and who are at risk of causing harm from substance misuse.

International research and experience tell us that testing for alcohol and drugs is most effective when it’s done alongside appropriate interventions. Corrections staff have a suite of rehabilitation options available and are trained to identify the most appropriate intervention for each individual. Testing is therefore another tool alongside programmes and motivational approaches that allows us to work with people to support change and help keep communities safe.

Every year, approximately 5,000 people serving community-based sentences/orders and around 15,000 bailees have an alcohol and/or drug abstinence condition imposed upon them. For probation officers and Police, an abstinence condition has traditionally been problematic to manage as non-compliance was difficult to detect and even more difficult to evidence in court. This is because legislation did not provide clear authority to test people serving a community-based sentence/order, even when they were subject to abstinence conditions.

The Alcohol and Other Drug Testing (AODT) of Community-based Offenders and Bailees Legislation Bill, introduced in July 2014, addressed that problem by creating an explicit legislative mandate for AOD testing of people serving a sentence/order and bailees subject to abstinence conditions.

On 8 November 2016, the Bill received its third reading and was divided into a number of Acts (Sentencing (Drug and Alcohol Testing) Amendment Act 2016), superseding existing legislation and enabling testing to occur in the community from 16 May 2017.

Two year trial in the Northern region

On 1 March 2016 the AODT Governance Board (comprising Corrections and Police staff) elected to trial AOD testing capability in the Northern Region for 24 months. The Northern Region was chosen as it represents 40% of the national target group of people with abstinence conditions. A trial enables Police and Corrections to test and understand the different technologies and their capabilities, and to identify the ideal frequency of testing and response requirements.

The trial uses a mixture of:

- Urine testing for drugs and alcohol (conducted on a randomised basis and where there are reasonable grounds)

- Breath alcohol testing (BAT) of bailees, and of specific people on sentence/order

- Alcohol detection anklet (ADA) monitoring for a small number of people who are at a high risk of causing harm if they consume alcohol.

It is expected that these testing and monitoring approaches will lead to:

- Reduced drug and alcohol use amongst offenders and bailees with an abstinence condition

- Improved compliance with conditions of sentences and orders, including bail

- Improved engagement with rehabilitation services

- Reduced harm caused by alcohol and other drug misuse through a change in the rate of offending

- Individual health benefits.

The trial began on 16 May 2017 for Community Corrections at two sites and extended to the remainder of the Northern Region from 1 September 2017. The staged approach provided for testing of processes and procedures with a smaller cohort which allowed for consolidation and further amendments to be made to enable a successful roll-out to a wider audience.

Event-based urine testing (e.g. if the probation officer has cause to suspect an offender may not comply with their abstinence condition) has now been made available to other regions on a case-by-case basis. ADA and random urine testing remain limited to the Northern region.

The trial will end in May 2019. Decisions to extend the service will be made closer to this time and after evaluation, in which case a national roll-out would be planned and implemented.

Why are we testing for alcohol and drugs?

We know that alcohol and drugs are an issue amongst offenders. A recent study found that 47% of New Zealand prisoners had received a diagnosis of a substance use disorder within the last 12 months, and 87% of prisoners had a lifetime diagnosis (Bowman, 2016). It’s also estimated that more than 50% of crime is committed by people under the influence of drugs and alcohol.

Testing for alcohol and drugs allows us to better intervene with a person according to their identified AOD needs. People often understate their use, believing that honesty will only get them into trouble if they have an abstinence condition. Testing provides an evidence base for treatment and allows us to open dialogue with a person about their AOD use. This means we are able to target a person’s intervention to their actual need. This aligns to the Risk-Needs-Responsivity model (RNR) adopted by the Department of Corrections, which works to ensure the right interventions are being delivered to the right people at the right time.

We have many tools to determine a person’s level of risk, both static and dynamic, and also their need. One such screening tool is the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Tool (ASSIST), which can identify someone’s use of each substance and the impact this has on their life and wellbeing. AOD testing is another tool for determining the level of intervention appropriate for each individual.

International literature and New Zealand experience suggests that testing alone does not reduce re-offending or protect communities from harm. Positive outcomes are only achievable with the accompaniment of comprehensive case management and a suite of rehabilitation programmes delivered with a person-centric approach. To this end, the focus of the trial has been two-fold – the testing itself and the use of suitable intervention options for those found to be using alcohol or drugs.

How and who are we testing?

The majority of Corrections testing is randomised urine testing. Once an abstinence condition is imposed, the individual is assigned to a testing tier by a probation officer. This is a two step process where an automated calculator provides the initial tier (based on static risk factors) and the probation officer then uses their professional decision-making to determine the final tier based on other factors known about the case which may affect the level of risk in relation to alcohol and drugs.

Cases can be assigned to tiers one, two, three or four, which determine the frequency of their testing. Tier one is reasonable grounds urine testing only. This means a probation officer can request a test if they have cause to suspect a person is not adhering to their abstinence condition. Alternatively, the probation officer can organise a test if they become aware of a potentially high risk situation (e.g., reunion, tangi, special birthday) and choose to test after the event.

Those on tiers two and three are entered into a “randomiser”, where tier two is set at a lower rate than tier three. At the beginning of each month the randomiser is run and a number of cases are assigned for testing. A centralised team at national office organises this testing to occur throughout the month and liaises with the probation officer for an appropriate time, usually to coincide with a report-in. Each person is given a short window of notice prior to their test (up to 24 hours) which allows them to organise themselves but not long enough to successfully compromise the test (e.g., by abstaining, dilution). Those on tiers two and three are also subject to reasonable grounds testing.

People considered at a high risk of causing alcohol related harm are allocated to tier four and, if suitable, are fitted with an alcohol detection anklet (ADA). The anklet is worn 24/7 and can determine if a “drinking event” has occurred based on the way a person excretes alcohol through their skin. It takes these “transdermal” readings in half hour intervals. The results from the anklet are not supplied in real time, rather a daily report is sent to the central AODT coordination team, for dissemination to the probation officer. If a probation officer believes a person is suitable for ADA they refer them through the regional high risk response team. All cases on tier four are also usually placed on a random regime (tier two or three) and are subject to reasonable grounds testing. This is because ADA does not measure drug use. The exception is if the individual has only been given a condition for alcohol whereby a random drug testing regime is not necessary.

If a person’s risk/need changes throughout their sentence or order, the probation officer can choose to increase or decrease their testing tier.

The Police use breath alcohol testing (BAT) for bailees and are working through the processes to also incorporate urine testing of defendants on electronically monitored (EM) bail. They are also using ADA for their highest risk defendants on EM Bail.

Working together

With increased monitoring, some concerns were expressed by staff regarding the working relationship between the offender and the probation officer. Probation officers are trained to operate in the spirit of motivational interviewing and the intention of testing is not solely to hold people to account. Instead, testing provides evidence that allows probation officers to make professional decisions that assist with rehabilitation and harm reduction.

The combination of motivational interviewing, appropriate programmes and testing provide the right foundation to support change.

It is accepted that this can be a difficult cohort of people to motivate to address their issues with alcohol and drugs. Enforcement action (such as formally “breaching” a person, or, in some cases, recalling them to prison) is sometimes appropriate together with other actions (increased reporting, referral for programmes, targeted motivational approaches) to balance personal accountability with opportunities for intervention and support.

What tools and interventions are available to probation officers?

There are many interventions available for alcohol and drug issues, ranging from low to high intensity. For those with a lower assessed need, probation officers can deliver brief interventions when the person reports in. Alternatively, probation officers can refer to external services such as Care NZ and Salvation Army where someone presents with moderate to high needs. Corrections funds residential services and even contracts a free 24/7 helpline; “RecoveRing” is specifically for offenders to call, whether they are struggling with their substance use or just want further information. Probation officers have easy access to all the rehabilitative options available in an interventions catalogue on the Corrections intranet.

What’s been happening on the trial?

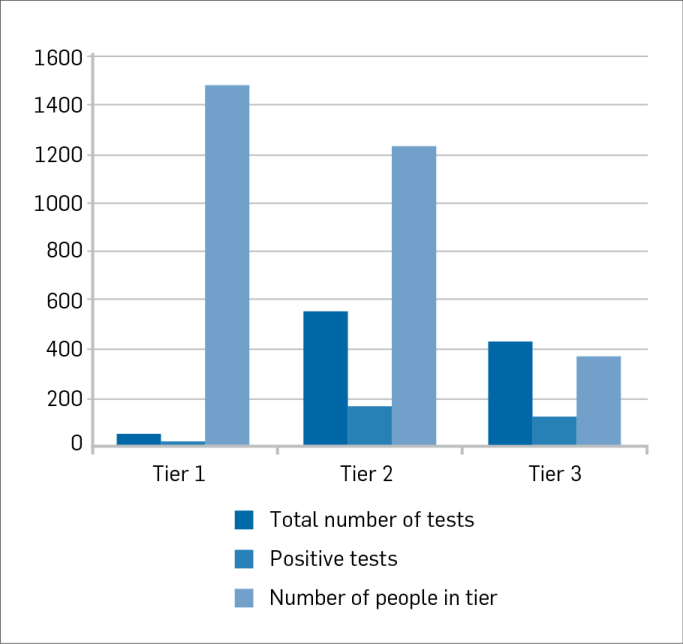

The following graph shows the number of positive urine tests for each tier since the beginning of the trial:

The total number of cases assigned to a testing tier was 3,080 at 1 March 2018. At that date there had been 1,046 urine tests in total, of which 306 have returned positive.

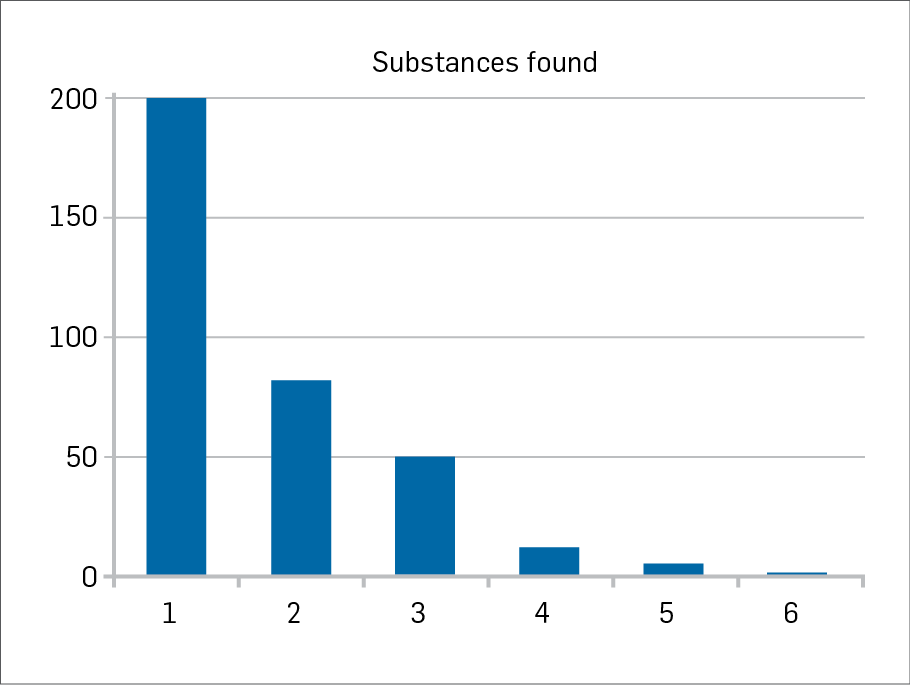

While most (199 tests) returned positive for one substance, many were found with two or more substances as per the following table:

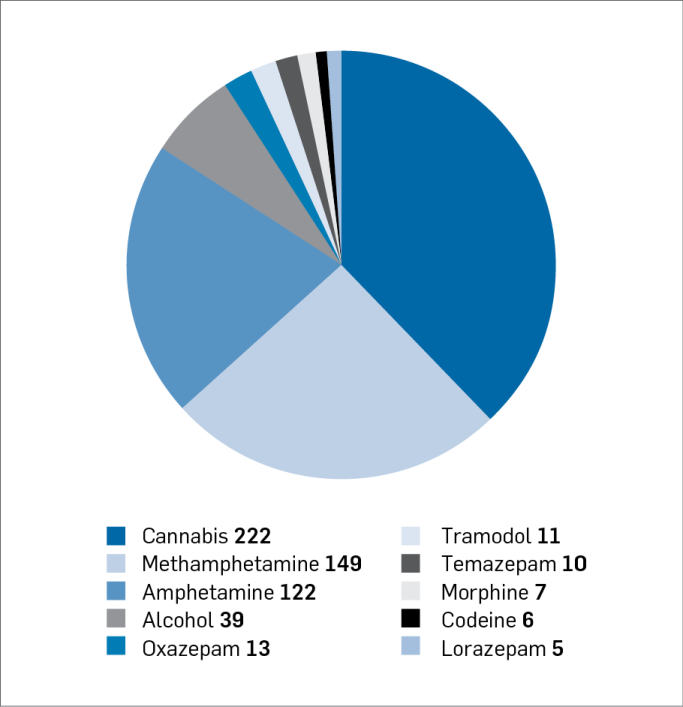

A breakdown of the top 10 substances found is as follows:

Cannabis was by far the most common substance detected. High rates of methamphetamine and amphetamine were also found.

In respect of ADA, at 1 March 2018 there had been 51 cases monitored through an anklet since the trial began (Police and Corrections both monitor in this way). Only four people had returned confirmed drinking events and when compared to the number of “tests” (every half hour while the anklet is worn) that equates to a sober rate of 95.9%. International research conducted on similar devices has found those who wear the anklet for 90 days have a lower recidivism rate and in cases where recidivism occurred, this was significantly delayed (Flango & Cheesman, 2009). The sober rates experienced to date are encouraging.

How are we responding to positive tests?

Data was taken from 1 September 2017, the day the trial went live to the entire Northern Region, to 4 April 2018. Between these dates 241 positive tests were returned for 216 offenders.

Given that only one response was recorded by the AOD Testing Coordination Team (AODTCT) for each positive test it was difficult to know from the data alone what exactly has been happening in the journey of each person tested. A deeper dive was therefore necessary to obtain a more realistic picture.

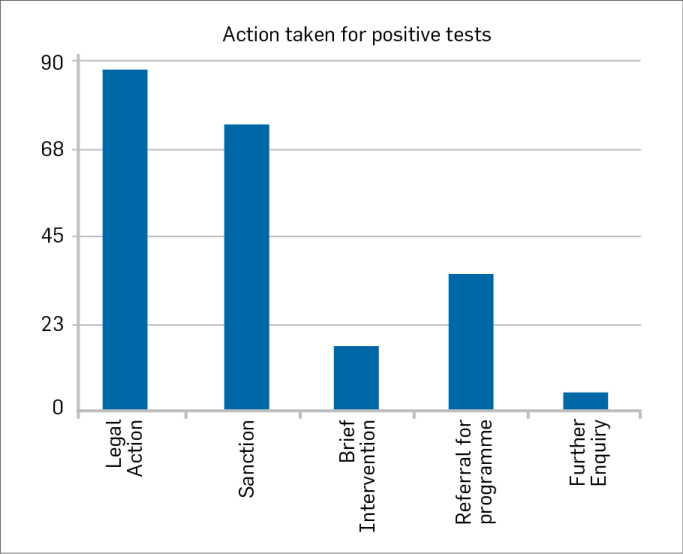

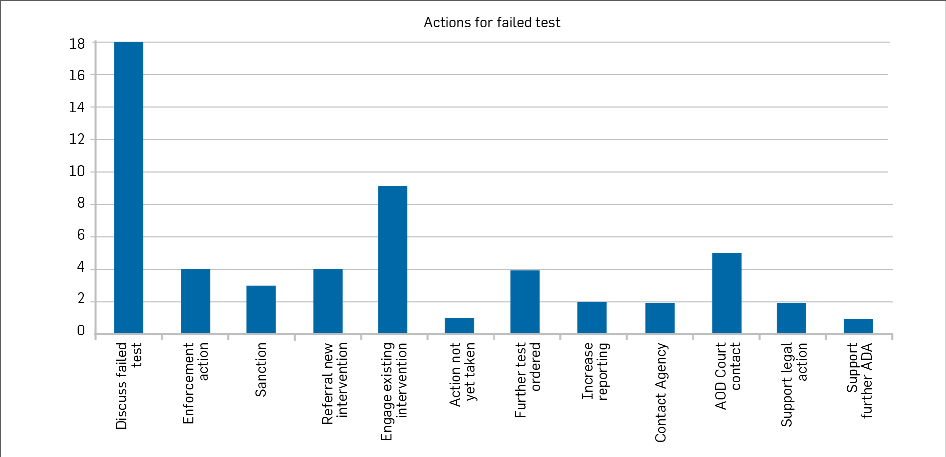

Actions were recorded for 220 of these tests as shown in the graph below:

Information recorded in file notes for 20 people who returned failed tests for alcohol and/or drugs was examined. For these 20 people, a total of 55 actions were taken. The information obtained was indicative of the complexity of each single case. Five of those examined were attending or had completed the specialist AOD Treatment Court . In all of the cases where these people had returned positive tests they were brought back before the judge of the AOD Treatment Court to discuss the way forward. One of these people, who has completed Higher Ground, the Salvation Army Bridge Programme and who attends Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, was encouraged to re-engage with current intervention provider CADS and other supports.

In some cases, probation officers were engaging with community mental health services as well as intervention providers. In one case the probation officer was working with Oranga Tamariki as the person testing positive was heavily pregnant.

In all but two cases, the probation officers had recorded having conversations with the person about their positive result, including how it would inform future management. In one case, no action had yet been taken, indicating that the positive result had only just been received.

In higher risk cases, a positive result was used to support an application to maintain ADA past 90 days and in one case, where the person had a number of breaches before the court, it was used to support an application for an Extended Supervision Order.

This data tells us that testing people for alcohol and drugs is effective in beginning and/or maintaining dialogue around substance abuse issues, which can be used to support new or existing intervention while holding people to account for non-compliance with abstinence conditions.

Moving forwards

Testing people on community-based sentences/orders for alcohol and drugs is still relatively new to New Zealand Community Corrections, but at the time of writing (May 2018) things are tracking well.

An interim evaluation in February 2018 found that probation officers were generally confident they knew how to respond to positive test results. They expressed a general preference for rehabilitative responses rather than breaches, and identified community safety as the most important factor in making those decisions.

A person’s risk to the community is always at the forefront of our practice. The more we know what the risk factors are and the extent of these, the greater chance we have at succeeding in reducing re-offending. Testing for alcohol and drugs provides real evidence for managing a person’s risk, allowing probation officers to make informed decisions that best support the person through their sentence and beyond.

References

Bowman, J. (2016) Co-morbid substance abuse disorders and mental health disorders among New Zealand prisoners. Practice, The New Zealand Corrections Journal, Vol 4, Issue 1, 15 – 20. Department of Corrections

Flango, V. E., & Cheesman, F. L. (2009). The effectiveness of the SCRAM alcohol monitoring device: A preliminary test. Drug Court Review, 6(2), 109–134.