Te Ara Tauwhaiti - Kaupapa Māori supervision pathway for programme facilitators

Ana Ngamoki

Senior Advisor, Service Development, Department of Corrections

Author biography

Ana has whakapapa connections to Te Whānau a Apanui and Te Whakatōhea in the Eastern Bay of Plenty. Following completion of a Bachelor of Social Sciences and Bachelor of Laws through the University of Waikato in 2012, she joined the Department of Corrections as a programme facilitator. She delivered programmes at Waikeria Prison and worked for a year at the Tai Aroha residence in Hamilton. Ana has been employed as a Senior Advisor in Programmes and Interventions since June 2017, and is currently working in the Contracted Programmes Team.

Keywords: Kaupapa Māori, Supervision, Department of Corrections, Cultural Responsiveness, Māori

Acknowledgements

“Ehara tāku toa i te toa takitahi, engari he toa takitini kē.”

E te ihi, e te wehi, e te wana, e te mana, e te tapu o nga ihuoneone, ngā ringa raupa i eke panuku, i eke Tangaroa. I te orooro, i te oromea, i tukituki ai koutou, i tataia ai koutou. Ko koutou mā te pītau whakareia o te waka nei, te takere waka nunui, nga kaiurungi o Te Ara Tauwhaiti kua hora nei! Ko Daniel Hauraki, Tui Armstrong, Jason Northover, Mate Webb, Heston Potaka, Barney Tihema rātou ko Neil Campbell - he tika, ka mihi.

“My strength is not mine alone, but comes from the collective efforts of others.”

To those who have contributed, to those who worked diligently to see this project complete: The journey required constant adjustment and fine-tuning to changing variables. Your leadership can be likened to that of the front of a waka breaking through the swells, the leaders who have directed and navigated Te Ara Tauwhaiti to completion. Daniel Hauraki, Tui Armstrong, Jason Northover, Mate Webb, Heston Potaka, Barney Tihema and Neil Campbell - you are deserving of acknowledgement, and it is only right that we recognise you.

Introduction

The Department of Corrections is committed to ensuring staff are supported to engage in a culturally responsive manner with those in our care. It is well documented that Māori are over-represented in all aspects of the criminal justice system. As a result, Corrections has a specific focus on ensuring staff are working in a culturally responsive manner with Māori. In programme delivery, one aspect of this support is provided through Kaupapa Māori supervision. This is delivered by the senior advisors cultural supervision, Māori Services Team, to approximately 270 internal programme facilitators who deliver the medium intensity suite of rehabilitation programmes. The framework which has been developed as guidance in this space is called Te Ara Tauwhaiti (the tenuous pathway).

From cultural supervision to Kaupapa Māori supervision

In the past, cultural supervision was provided by external supervisors throughout Aotearoa. While experts in their chosen fields, it soon emerged that there were inconsistencies in practice, as there was no framework to guide them.

In 2015, the decision was made for cultural supervision to be delivered by internal Corrections staff. A tiered approach was approved by Corrections’ Service Development Senior Leadership Team (SD-SLT) and Corrections Services Senior Leadership Team (CS-SLT) in 2016. This approach saw supervision separated into three sections: learning and education, supervision, and advice and support. The renaming of these tiers as “Kaupapa Māori” was a deliberate move away from cultural supervision – the goal being to support facilitators towards becoming bi-cultural practitioners. Kaupapa Māori supervision ensures that responsiveness to Māori is placed firmly at the centre of practice and supervision discussions. Furthermore, it acknowledges that different cultural perspectives exist in all aspects of our work, which can have an impact on development and practice.

Kaupapa Māori supervision “is named according to the value systems on which it is based, building on the notion that values, protocols and practices of [Māori] culture…are being adhered to” (Elkington, 2014, p.67). It provides a space to discuss unconscious cultural biases, reflections and assumptions within the context of the Māori worldview.

The definition of Kaupapa Māori supervision in programme delivery is that it is a bi-cultural process underpinned by core Māori social values. These values are employed as a foundation for working responsively with Māori in the Department. It is a formal, bi-cultural process where these core social values are role-modelled via tuakana-teina (mentoring) relationships and applied by the supervisors in session. This serves as a parallel process for supervisees, enabling them to develop knowledge and skills, and mirror learning and development through self-reflection, self discovery and a Māori cultural lens. Kaupapa Māori supervision is designed for facilitators to reflect on their own cultural lens within the context of Māori values, processes, principles and protocols and how this impacts or contributes to practice and learning.

The role of the supervisor is to promote supervisee development and awareness of Māori cultural concepts and processes. This is achieved through exploring assumptions; assisting with developing awareness of a facilitator’s own cultural identity; and providing alternative frameworks, models and concepts to broaden supervisee awareness, knowledge and skill base to deal with cultural issues. Kaupapa Māori supervision also provides a safe space to share thoughts and ideas, and practise Māori cultural tools (pepeha, mihi, and whakataukī).

Te Ara Tauwhaiti

Te Ara Tauwhaiti derives from “Te Ara Tauwhaiti i te Pu-motomoto” from one of the many journeys of Tāne. The name signifies the path Tāne climbed to reach Tikitiki-o-Rangi (the highest heaven) where Io (supreme being) dwells. Tāne reached the doorway of Tikitiki-o-Rangi by riding on a whirlwind. Te Pu-motomoto is the name of the doorway. The challenges Tāne faced along the way, particularly from Whiro , parallel challenges practitioners face, and are referred to as Te Ara Tauwhaiti, or the “tenuous pathway”.

The ascent of Tāne will be the metaphor used for the Kaupapa Māori supervision pathway for programme facilitators by supervisors. Following the separation of Rangi and Papa, Tāne underwent a number of purification rites before ascending the heavens to Io. During this journey, not only did he undergo further purification rites, but he faced challenges from Whiro; both in his ascent to, and descent from, Tikitiki-o-Rangi. These challenges required solutions – not only from Tāne himself, but also from others involved in his journey, such as his brothers.

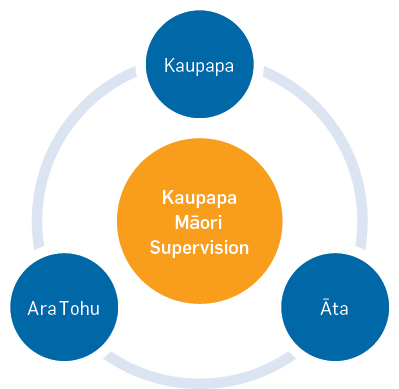

Te Ara Tauwhaiti consists of three sections: Kaupapa, Ara Tohu and Āta. It is expected that discussions will be undertaken through the lens of Kaupapa. To give discussions depth, Ara Tohu will be applied. The behavioural principles of Āta provide guidelines for how supervisors are expected to engage in supervision with supervisees.

Kaupapa

There are six kaupapa which underpin Te Ara Tauwhaiti. They are:

Kaitiakitanga

– Kaitiakitanga is a constant acknowledgement that “people are engaged in relationships with others, environments and kaupapa where they undertake stewardship purpose and obligations.” (Pohatu, 2008, p.271). Essentially it is about “taking care of” relationships, space, knowledge, skills and self by “nurturing the light and potential within” others (aki i te tī o te tangata). In practice, both supervisors and supervisees have kaitiaki obligations. The supervisor is responsible for establishing an environment which reflects Māori protocols, processes, principles and practice, as well as Māori cultural concepts and enabling tools. They are guided by the learning needs, development, reflections, knowledge and skill set of the supervisee. Underlying the supervisor’s kaitiaki obligations is ensuring that Kaupapa Māori (values, principles, content) are being adhered to. The supervisor is guardian of the supervision venue and process.

The supervisee is responsible for ensuring they are prepared for a session (i.e. agenda items for discussion, identifying practice issues, karakia, mihi, waiata, whakataukī and self-reflections) in line with Kaupapa Māori. They are guardians of themselves and their learning and development. The expression of kaitiakitanga creates āhurutanga (safe space). Fundamental to the establishment of āhurutanga is the need for “ngākau māhaki” (to be humble) from supervisors and supervisees, regular self-reflection and being pono (honest).

Manaakitanga

This kaupapa guides us in how we should interact in relationships with others; it is the expression of aroha, generosity, respect, kindness, support and care within these interactions. In the supervision space, manaakitanga looks at how value can be added to supervisory relationships, knowledge, skill set, kaupapa and development, while acknowledging that it is a mutual elevation of mana. This means the supervision process enhances the mana of all involved in the process.

The expression of manaakitanga also leads to āhurutanga (safe space). The supervisor is expected to supervise in a manner which is mana-enhancing and mana-protecting. As a priority, the supervisor will consider how value can be added to interactions within the supervision space, as well as to the developmental areas of individual supervisees. This mirrors to the supervisee the knowledge and skill set required to displaying manaakitanga in their own group sessions.

Rangatiratanga

This refers to the concept of leadership, and the ability of the individual to weave together (ranga) groups/people (tira) to enhance productivity. At the heart of rangatiratanga is the recognition and nurturing of relationships.

In the supervision space, rangatiratanga enables supervisors to support supervisees in realising they are the decision makers and navigators of their own journey. The expectation is that supervisees take responsibility for their supervision by ensuring self-reflections are undertaken using a Māori cultural lens, identifying agenda items for discussion, goals, practice issues, and any processes which adhere to Māori values, protocols and processes. It is also important that the supervisee is prepared prior to supervision by identifying what it is they would like to gain from the session. The supervisor’s role is to be guided by what the facilitator/s bring to the session and weave these through a supervision session.

Whanaungatanga

This kaupapa focuses on whakapapa as a connective device that links individuals through generations. It also has a focus on building non-kin relationships. It is understood that relationships are developed over time through shared experience, common goals and working together.

In the supervision space, whanaungatanga requires the building of rapport, therapeutic alliance, trust and developing safe space (āhurutanga). In order to work effectively with others, it is important that facilitators understand their identity, the cultural worldviews they hold and how this impacts interactions in relationships. Supervisors explore with supervisees Māori cultural tools aimed at enhancing whanaungatanga, such as the use of pepeha, mihi and finding commonalities with group participants. This role modelling of whanaungatanga and use of Māori cultural tools mirrors expectations required for building whanaungatanga between facilitators and programme participants

Wairuatanga

This kaupapa focuses on “the physical and spiritual dimensions of thinking, being and doing, and influences the behaviour of individuals in different spheres of life” (Jolly, et al., 2015, p.10). It is believed (and valued) that the spiritual and physical dimensions are held together by mauri (life-essence/life force). Therefore, when exploring supervision agenda items through the lens of wairuatanga, it is also important to discuss it within the context of mauri and the different states of mauri, such as mauri tau (to be deliberate, without panic) and mauri oho (startled mauri).

Pitama, Robertson, Cram, Gillies, Huria & Dallas-Katoa (2007) consider that in the practical application of wairua, there are two key components which allow for exploration and discussion. The first component is the physical aspect, where discussions are focused on an earthly or grounding attachment, such as people, items, tāonga or places where one feels connected, safe and at peace. The second component involves an exploration of spiritual frameworks, such as values, beliefs, spiritual journeys, norms and cultural lens. It is expected that supervisors will guide discussions in a manner consistent with this framework in the provision of supervision.

Pūkengatanga

This kaupapa means skilled, to be versed in, expertise. It is important that supervisees are equipped with the tools to enable them to display Māori values, protocols and processes. Pūkengatanga recognises the need to apply specific knowledge and skills to support kaupapa, protocols, processes, theories, concepts and models.

Summary

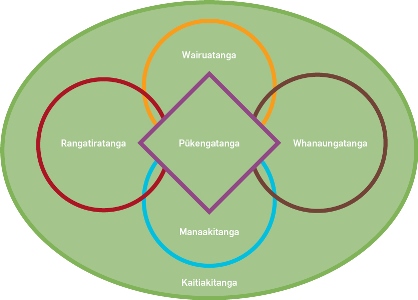

Kaupapa is the framework which underpins Te Ara Tauwhaiti. The discussions between the supervisor and supervisees are guided by these kaupapa in the provision and reception of Kaupapa Māori supervision. The visual representation below highlights that kaitiakitanga is the overarching kaupapa within the Kaupapa Māori supervision space, as “taking care of” relationships, space, knowledge, skills and self by “nurturing the light and potential within” others (aki i te tī o te tangata – to nurture the indescribable light of a person) is highly valued within te ao Māori. Conversations and discussions are explored using these different kaupapa or lenses as required. It must be acknowledged that these kaupapa do not exist or operate in isolation, and throughout discussions both the supervisor and supervisees may move in and out of these different spaces, depending on the topic of conversation. Finally, linking the kaupapa together is Pūkengatanga; it is recognised that in order to apply the kaupapa, one requires the knowledge and skill base to display and express the kaupapa.

Ara Tohu

In order to navigate supervision sessions using Kaupapa, six Ara Tohu (sign posts) are used. The aim is to encourage exploration of self-reflections, assumptions, biases and experiences which arise for programme facilitators in the course of their role. Given there are iwi and hapu variations to Ara Tohu, supervisors and supervisees are encouraged to use regional definitions. In order to find out about regional differences, staff can contact the Māori Services Team, local hapū or iwi kaumātua, iwi organisations, or credible written references (e.g. teara.govt.nz, iwi based books).

There are six Ara Tohu; Wai (water, fluidity, depth); Rā (sun, shining down, illumination); Mā (pure, untainted); Whā (four, “from the four winds”); Pū (seed, growth, development, foundation); and Kai (food, sustenance, “the food of a leader is korero”).

Wai

For the purposes of supervision, we translate Wai as “water” and as a personal noun. Wai acts as a metaphor for group dynamics. Supervisors use it to explore discussions in supervision. This role-models to the supervisees how Wai could be utilised to understand the groups they are facilitating. Some examples of the application of Wai as an Ara Tohu in supervision sessions include discussions about:

- Toka tū moana – who stands out in the group, who are the leaders?

- Wai marino – who brings the calmness into the group?

- Wai tapu – who needs clearing in the group? (What are the blocks?).

As a personal noun, Wai includes examples such as “ko wai tōna īngoa?” (e.g. what’s his/her name?) This reiterates the need for whakawhanaungatanga and the requirement for supervisors to role model relationship building processes in supervision, such as pepeha, whakataukī, waiata and whakapapa. Another example is the song “Mā Wai Rā e Taurima?” (Who Will Assume Responsibility?). This example encourages facilitators to take responsibility for their learning in the supervision space. This role-models to facilitators how to encourage tāne and wahine in our programmes to take responsibility for their own journeys.

Rā

In the context of Kaupapa Māori supervision, Rā as an Ara Tohu is a metaphor relating to the sun and light, as well as distance from the present time, either in the past or future. In Te Ao Māori, the sun was used as an identifier of time and seasons. For example, “te poupoutanga o te rā” refers to the sun being at its highest point during the day; often referred to as midday.

This Ara Tohu focuses on bringing practice under the bright light of day so all is revealed. This includes practice, goals, progress and the incorporation of Kaupapa Māori as a treatment response. It encourages supervisees to reflect on their current practice and progression pathways. This approach also reflects the importance of being intentional, and moving with respect and integrity (āta haere).

Mā

Like many other kupu, Mā has a number of definitions. For the purposes of Kaupapa Māori supervision, “Mā” translates to the English word “pure” (untainted, clean, white). Mā also equates to the Māori word “pure” (a ceremony or rituals undertaken to remove tapu).

It can also be used as a term of inclusion when applied after names, or refer to removing blocks through the process of supervision (to clear the way) or as an indication of future action or responsibility.

This Ara Tohu can ensure that both in the supervision space, and within programmes, instances of tapu are dealt with appropriately, using the relevant Māori cultural tools (such as karakia or kai). Mā requires that the supervisees focus on “stripping back” or examining assumptions, unconscious biases or cultural distortions which arise from their own cultural perspective/s, misrepresentations or misinformation which the supervisees may hold themselves or hear in group from participants.

Whā

The kupu “Whā” most commonly translates to the number four. For the purposes of Kaupapa Māori supervision, Whā in its numerical form will be explored via the saying, “ngā hau e whā” which means “the four winds”. Whā can also be used as a prefix meaning “to cause something to happen”.

The saying ngā hau e whā is often used to symbolise the gathering of people from diverse locations in one place. In Kaupapa Māori supervision, cultural diversity must be acknowledged and respected. Given it is a Kaupapa Māori space, cultural diversity must be considered within the context of te ao Māori, therefore allowing for bi-cultural relationships and bi-cultural practitioners. This Ara Tohu focuses on facilitators considering their own worldviews and cultural perspectives within the context of te Ao Māori.

Pū

The Ara Tohu “Pū” translates as seed, foundation, growth and development. One extension of Pū is the word pūtake which means origin, cause or root. This Ara Tohu relies on the practice goals and self-reflections of the supervisees. Reflections (including critical reflection) should focus on the supervisees’ understanding and application of Māori cultural tools; practice goals; and professional development in this area. The other important focus is on the origins of any distortions or blocks the supervisee may have and what they may need to do to whakawātea, or clear these so that, like Tāne, they can progress to the next level.

This Ara Tohu also focuses on the responsibilities of the supervisor within the supervision session. The supervisor is required to establish an optimal environment alongside the supervisee which will nourish potential and support growth. The supervisor must work alongside the supervisee to establish the conditions which will enable this.

Kai

The final Ara Tohu used to explore discussions through the lenses of Ngā Kaupapa is “Kai” or food. Kai is a source of nourishment or sustenance for people. The whakataukī, “ko te kai a te rangatira he korero” which translates as, “the food of chiefs is dialogue” is appropriate for guidance in the Kaupapa Māori supervision space. The intention of this Ara Tohu is to nourish best practice by sharing correct information using credible sources through the use of wānanga (open dialogue).

Further expectations under this Ara Tohu include that an individual’s Te Whare Tapa Whā is being nourished through a supportive supervision environment and sharing of correct information; and that take home messages and learnings are shared between the supervisor and supervisee. A final expectation is the tracking of practice goals and the steps being taken towards achieving these goals.

Summary

Ara Tohu are used to navigate the Kaupapa; the framework which underpins Te Ara Tauwhaiti. The use of Ara Tohu in Kaupapa Māori supervision allows for in-depth exploration of agenda items through Kaupapa. It allows for hoa-haere (valued companions) such as waiata, pūrākau, whakataukī and so forth to be activated to complement the agenda items being raised by supervisees. The activation of hoa-haere ensures that Māori values, processes, principles and protocols are maintained and adhered to. It ensures the focus remains on a Māori cultural lens, that Māori cultural tools are used as a treatment response, and that the supervision space remains bi-cultural.

Āta

The final aspect of Te Ara Tauwhaiti to be discussed is the approach of the supervisor which is role-modelled to the supervisees. This is a Kaupapa Māori approach to working with others, and in particular, implies guidelines which tell us how to enter, engage and exit relationships respectfully.

These guidelines are called Āta. This is “a behavioural and theoretical strategy employed by Māori in relationships” (Pōhatu, 2005, p2). As a cultural tool, it is designed to inform and guide our understanding of respectfulness in relationships and working towards wellbeing. Using Āta deliberately places Māori thought and knowledge at the centre of interactions to inform and guide practice (Pōhatu, 2005).

It is expected that throughout the supervision process, supervisors will engage with supervisees using Āta processes. The Āta phrases below provide guidelines as to how supervisors may engage with supervisees (Pōhatu, 2005, p5):

Takepū/Principles | He whakamāramatanga: Definitions |

|---|---|

Āta -haere | Be intentional, deliberate and approach reflectively, moving with respect and integrity. It signals the act of moving with an awareness of relationships, their significance and requirements. |

Āta -whakarongo | To listen with reflective deliberation. This requires patience and tolerance, giving space to listen and communicate to the heart, mind and soul of the speaker, context and environment. It requires the conscious participation of all senses, the natural inclusion of the value of trust, integrity and respectfulness. |

Āta -kōrero | To communicate and speak with clarity, requiring quality preparation and a deliberate gathering of what is to be communicated. This is to ensure a quality of presentation (kia mārama ki te kaupapa), to speak with conviction (kia pūmau ki te kaupapa), to be focused (kia hāngai ki te kaupapa). |

Āta -tuhi | To communicate and write with deliberation needing to be constantly reflective, knowing the purpose for writing. Consistently monitoring and measuring quality is implicit. |

Āta -mahi | To work diligently, with the conviction that what is being done is correct and appropriate to the tasks undertaken. |

Āta -noho | Giving quality time to be with people and their issues, with an open and respectful mind, heart and soul. This signals the level of integrity required in relationships. |

Āta -whakaaro | To think with deliberation, allowing space for creativity, openness and reflection. The consequence is that action is undertaken to the best of one’s ability. |

Āta -whakaako | To deliberately instil knowledge and understanding. There are clear reasons why knowledge is shared: to the appropriate participants, in the required manner, time and place |

Āta -tohu | To deliberately instruct, monitor and correct, grounded knowledge being a constant and valued companion. Cultural markers such as kaitiakitanga (responsible trusteeship) are then accorded safe pace to enlighten how and why relationships should be maintained. |

Āta -kīnaki | To be deliberate and clear in the choice of appropriate support to enhance positions taken. |

Āta -hoki mārire | To return with respectful acknowledgement of possible consequences. |

Āta -titiro | To study kaupapa with reflective deliberation. |

Āta -whakamārama | To inform with reflective deliberation, ensuring that the channels of communication at the spiritual, emotional and intellectual levels of the receiver are respected, understood and valued |

Conclusion

Supervisors were trained in the delivery of Te Ara Tauwhaiti in March 2018. It is currently being rolled out nationwide to programme facilitators. Some regions set aside a training day for all programme facilitators and principal facilitators, while other regions are introducing the framework in smaller groups.

To ensure we maintain the integrity of the framework, the Department will provide ongoing training and supervision for supervisors, a process for moderation of reports, and monthly AVL peer support between supervisors. Quality assurance will need to be undertaken to ensure there is adherence to the purpose and practice of the framework.

Te Ara Tauwhaiti provides a new direction and deliberate pathway which reflects, and is intrinsic to, a Māori worldview. This pathway is vital to ensuring that as Corrections staff, we continue to be innovative and challenge the way we work with Māori in our care.

References

Elkington, J. (2014). A Kaupapa Māori supervision context-cultural and professional. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work Review, 26(1).

Jolly, M., Harris, F., Macfarlane, S., & MacFarlane, A. H. (2015). Kia Aki: Encouraging Māori values in the workplace. Retrieved from [http://maramatanga.ac.nz/sites/default/files/14INT05%20-%20Monograph%20Internship%20UC.pdf]

Pitama, S., Robertson, P., Cram, F., Gillies, M., Huria, T., & Dallas-Katoa, W. (2007). Meihana model: A clinical assessment framework. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 36(3), 118.

Pohatu, T. W. (2005). Ata: Growing respectful relationships. Unpublished manuscript. Te Wānanga o Aotearoa. Manukau.

Pohatu, T. W. (2008). Takepū: Principled approaches to healthy relationships. In TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE CONFERENCE 2008 TE TATAU POUNAMU: THE GREENSTONE DOOR (p. 241).