Suicide in New Zealand Prisons - 1 July 2010 to 30 June 2016

Robert Jones

Principal Analyst, Service Development, Department of Corrections

Author biography:

Rob studied design at Massey University and, after graduating, was briefly employed at Corrections as a public information officer. He then spent five years as a freelance video editor, before returning to Corrections as a ministerial services adviser in October 2012.

Introduction

Suicide is a significant issue, both in our prisons and in our wider communities. The New Zealand Department of Corrections is committed to reducing the impact of suicide and self-harm on people in our care, their whānau, families, friends, and our staff.

Since 1 July 2000, Corrections has generally experienced between three to six suicides in prisons each year. In 2015/16 there were 11 deaths as a result of confirmed or suspected suicide. In light of this particularly high number, the Department of Corrections Executive Leadership Team commissioned a review of all 39 confirmed and suspected suicides in prisons from 1 July 2010 to 30 June 2016.

In order to address prisoners’ mental health issues and improve their quality of life, we have recently introduced a number of new initiatives. In 2016, the Justice Sector Fund granted funding to improve the management of offenders with mild to moderate mental health needs by introducing more specialised mental health clinicians into prisons and community corrections sites. We have also introduced social workers and counsellors in women’s prisons, provided support for vulnerable whānau of offenders with mental health disorders, and introduced supported living for community offenders with mental health needs. In 2017, Corrections developed a strategic plan titled, Change Lives Shape Future: Investing in better mental health for offenders. We also secured Budget 2017 funding to develop a new model of care to support prisoners who self harm or experience suicidal ideation while in prison, which will be trialled at three sites in 2018. We are pleased to report that the high number of suicides in 2015/16 has not continued in 2016/17, with only one suspected suicide in that period.

We acknowledge the loss of life that has made the review imperative to undertake:

“Ngā mate aituā o tātou

Ka tangihia e tātou i tenei wā

Haere, haere, haere.

The dead, the afflicted, both yours and ours

We lament for them at this time

Farewell, farewell, farewell.”

Background

International Context

Suicide is acknowledged as a serious international health problem. The World Health Organisation estimates that one suicide attempt occurs every three seconds, and one completed suicide occurs approximately every minute (World Health Organisation, 2007).

Suicide is often the single most common cause of death in correctional settings worldwide. These incidents can have far wider impacts beyond the immediate impacts for the person involved and their families. A prisoner’s self-harming behaviour can adversely impact on the wellbeing of staff and other prisoners. Prisons, jails and penitentiaries are responsible for protecting the health and safety of their prisoner populations, so, in addition, suicides can be subject to legal challenge and the related media interest can lead to political ramifications. Accordingly, reducing the number of suicides in prisons, jails and penitentiaries is a priority for all international jurisdictions (World Health Organisation, 2007).

New Zealand general context

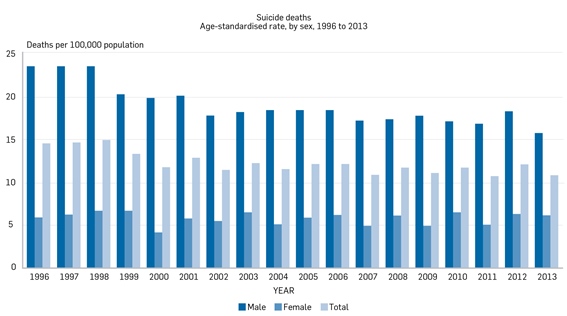

In New Zealand, approximately 500 people die by suicide annually, more than those who die in road traffic accidents and homicides combined. The table below outlines the age-standardised rates of suicide deaths per 100,000 people from 1996 to 2013 (Statistics New Zealand, 2017). The suicide rates for men declined from 1996 to 2000, and have since remained relatively steady: they were 23.8 per 100,000 in 1996 and 16.0 in 2013. In contrast, the suicide rate for women has remained low and relatively stable: it was 6.1 per 100,000 in 1996 and 6.3 in 2013.

New Zealand prison context

Suicide in New Zealand prisons has been a source of ongoing concern for many years. A number of research reports have highlighted that prisoners have higher rates of suicide and self-harm than the general population, and subsets of prisoners are particularly at risk, such as Mäori and youth prisoners (Mason et al, 1988; Skegg & Cox, 1993; Ministry of Health, 1996).

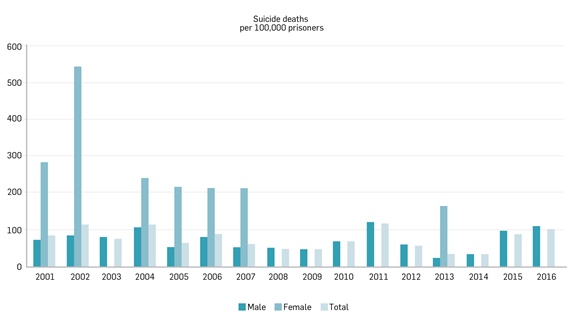

The table below outlines the rates of suicides per 100,000 prisoners from 2000/01 to 2015/161. The suicide rate for male prisoners was 73.1 per 100,000 in 2000/01 (n=4) and 112 in 2015/16 (n=11). The suicide rate for female prisoners was 286.3 per 100,0002 in 2000/01 (n=1) and 0 in 2015/16 (n=0). These rates are highly volatile due to a small sample size compared to the general population, particularly for female prisoners.

Review Method

The review aimed to build on previous studies and consisted of a retrospective data analysis of all 39 cases over the period 1 July 2010 to 30 June 2016. The data was collected through individual case analyses, which included details of the circumstances of the death, the demographics, history, social connectedness, and health status.

The review incorporated additional statistical data about the 39 cases sourced from Corrections’ internal reporting systems. Where possible, the aggregated data about the cases has also been compared to the wider New Zealand prison population, the wider New Zealand general population, and international prison suicides. Statistical data on these groups has been sourced from Corrections internal reporting systems, New Zealand coronial reports, national literature, and international literature.

Discussion of the cases

Corrections completed individual case analyses for all 39 prisoners, and themes from the analyses and related literature are outlined below.

Circumstances

The “circumstances” of the cases relate to their date of death, time of death, prison site, specific location (single or double cell) and means of suicide. The primary findings relating to the circumstances of the cases are outlined below:

- Time of death: Approximately half of the cases were identified as having died between 06.01am and 10.00am, and the remainder were distributed relatively evenly throughout the day. These results are generally consistent with international studies which found that most suicides occur in the early morning (Bennefield, 2012; Bartsch et al, 2015; Joukamaa, 1997).

- Prison site: The highest number of cases occurred at the largest prisons across the estate. Spring Hill Corrections Facility stands out as a large prison with a lower level of suicides over the review period than similar sized prisons.

- Specific location (single or double cell): All cases committed self-harm in their cells, and all except one were in single cells. Cases who died in single cells are over-represented compared to the total number of prisoners who occupy those cells. These results are consistent with international studies which highlight that single cells are a risk factor for prison suicides (Fruehwald et al, 2004; World Health Organisation, 2007).

- Means of suicide: The majority of the cases died by hanging and a wide range of objects were used as ligature points. These results are consistent with other international and national studies on the means of prison suicides (Hayes, 2012; Bartsch et al, 2015; Joukamaa, 1997; O’Driscol et al, 2007; Patterson & Hughes, 2008; Sakelliadis et al, 2013; White, Schimmel, & Frickey, 2002; Wobeser, Datema, Bechard, & Ford, 2002).

Demographics

The “demographics” of the cases relate to their age, gender, ethnicity and sentence status. The primary findings relating to the demographics of the cases are outlined below:

- Age: 25 to 29 year olds were over-represented when compared to the general prison population. 20 to 24 years olds were under-represented when compared to the overall New Zealand population statistics. There were no cases from 0 to 20 years of age, which is inconsistent with a previous national study on prison suicides. That study found that young prisoners aged 15 to 19 were at the greatest relative risk (Le Quesne, 1995).

- Gender: All of the cases except one were men, who were slightly over-represented when compared to the proportion of men in the overall prison population. All cases are believed to be cisgender with no cases recorded as transgender, intersex or any other gender variation. These results are generally consistent with international studies on prison suicides (Bartsch et al, 2015; Fazel et al, 2011; Fruhwald & Frottier, 2005; Opitz-Welke, Bennefeld-Kersten, Konrad & Welke, 2013; Patterson & Hughes, 2008).

- Ethnicity: Māori, Pacific and Asian prisoners were under-represented within the cases. New Zealand European and Other/Unknown prisoners were over-represented. The cases were inconsistent with current Māori suicide trends in the general New Zealand population, and inconsistent with Māori prison suicide trends in the mid-1990s (Le Quesne, 1995; Cox & Skegg, 1993).

- Sentence Status: Remand prisoners were over-represented in the cases when compared to the general prison population. These results are generally consistent with international studies which have found that remand status is a risk factor for suicides (Fazel et al, 2008; Hayes, 2012; Joukamaa, 1997).

History

The “history” of the cases relates to their time since admission into prison, nature of offending, security classification, risk of re-offending, other sentences, movement history, segregation status, gang affiliation, and New Zealand Parole Board recommendations or decisions. The primary findings relating to the history of the cases are outlined below:

- Time since admission: The majority died within a year of admission into Corrections’ custody.3 This finding is consistent with international studies which have found that prisoners generally die by suicide at an early stage of their confinement.

- Nature of offending: Violence offences were over-represented. These results are consistent with international studies, which have found that prisoners accused or convicted of violent crimes are at risk of suicide in prison (Fazel, Cartwright, Normann Nott, & Hawton, 2008; Hayes, 2012; Konrad, 2002).

- Other sentences: Prisoners on their second or subsequent sentences were over-represented among the cases. These results are consistent with the international literature, which found that the prisoners who made near fatal suicide attempts were significantly more likely than control groups to have had two or more previous prison sentences (Rivlin, A. Hawton K, Marzano L, Fazel S, 2013).

- Segregation status: None of the cases were on directed segregation at the time of death, approximately half were on voluntarily segregation. The cases are over-represented when compared to the percentage of the prison population who were under voluntary segregation, and under-represented when compared to the percentage of the prison population on directed segregation. These results were inconsistent with international studies which found that a disproportionate number of prisoners die by suicide while under “directed segregation” type conditions (Metzner & Hayes, 2006).

- Gang history: Gang membership was slightly over-represented within the cases: 38% (n=15) had a recorded gang affiliation and 62% (n=24) had no recorded affiliation. The Black Power and Mongrel Mob cases were generally consistent with the overall population.

Social connectedness

Social connectedness is regarded as an important protective factor against self-harm and suicide (World Health Organisation, 2007). However, people who are vulnerable to suicide may have poor social support because of their life course, rather than their being predisposed to risk because of a lack of social support (Beautrais, 2005). People may generate their own social environments, which reflect their temperament and genetic predisposition to mental illness (Kendler et al, 1997). As a result, social connectedness should not be seen as an environmentally created measure in isolation from a person’s individual temperament and other unique characteristics.

International literature has found that marriage is a protective factor against suicide in the general population (Klien, Bischoff, & Schweitzer, 2010) and in correctional settings (Bartsch et al, 2015; Benefeld, 2012; Hayes, 2012). The relationship status of the cases was cross referenced against visit applications to identify if they had partners and received visits from them: approximately 30% of the cases were married or had a partner outside of marriage or civil union, and the rest were single. These results appear consistent with previous studies in that most cases were single.

The review results also found that the majority of cases had records of some other forms of social contacts such as family contact or approved visitors.

It is important to note that social connections are dynamic and the above statistics represent records of connections throughout the case’s sentences of imprisonment, rather than the quantity and quality of connections at their time of death. Furthermore, in light of the need to consider social connectedness in the context of a person’s life course, some of the cases who could be viewed as social ‘loners’ had been so for many years both in the community and prison. As a result, it is difficult to draw strong conclusions about the overall social connectedness of the cases on the basis of this information.

Health

“Health” relates to general health, mental health, and at-risk and aftercare status. The findings relating to the health of the cases are outlined below:

- General health: Approximately 20% of the cases were noted as having “chronic” physical health conditions. Corrections holds limited national aggregated data on the physical health of the general prison population. As a result, comparing the health of the cases to the health of the general prison population is not possible.

- Mental health: Approximately half of the cases had a record of self-harm, a diagnosed mental health condition and a record of engagement with Forensic Services during the course of their sentence. Approximately 80% also had a record of alcohol or other drug dependence.

- At-risk and aftercare: 46% of the cases had spent no time in an At-Risk Unit (ARU). Of these cases, six had a recorded history of self-harm, and five had a diagnosis of depression. The remaining cases had spent time in an ARU at some point during their imprisonment. For the 12 cases where the time between exiting the ARU and death was identified: six died between one and seven days afterwards; one died between 14 and 30 days afterwards; and five died more than 30 days afterwards.

Offender management

The “offender management” of the cases relates to the status of their offender plans, access to psychological services, engagement with the Right Track approach, and Multi-Disciplinary Team management. The primary findings relating to the offender management of the cases are outlined below:

- Offender plan: A number of the cases pre-date the current case management framework that commenced in 2011. The majority of cases that took place from 2011 had an offender plan in place. The cases that had no plan in place primarily died within a few days of arriving into custody and, therefore, there was no legal requirement for an offender plan to have been completed. From 1 July 2014, case managers have been expected to meet with offenders within 10 days of allocation; in the cases where the offender had died within several days of reception, it is unlikely a case manager would have made contact.

- Psychological services: Approximately half of the cases had been seen by psychological services at some point during their sentence. The primary role of departmental psychologists is the provision of psychological assessment, offence-focused treatment, and advice about offenders who have a high risk of reconviction and imprisonment. However, they also support the mental health of prisoners where appropriate.

- Right Track: Right Track is a New Zealand prison-based framework that was introduced in 2012 and provides support and structure for active management principles and supports offender-centric practice. Right Track is about supporting staff to make the right choice and take the right action with offenders at the right time. The approach then encourages staff to influence offenders to do the same in their daily lives. A number of the cases had no recorded Right Track notes as they died prior to the implementation of the framework. Of the remaining cases, the majority had limited recorded evidence of right track engagement.

- Multi-Disciplinary Team (MDT) management: The majority of the cases had limited recorded evidence of MDT management or information sharing.

Behavioural themes

The World Health Organisation recommends that correctional organisations develop suicide profiles

that can be used to target high-risk groups or situations (World Health Organisation, 2007). An analysis by the principal adviser research in the Chief Psychologist’s team identified behavioural themes across the 39 cases, being themes for angry/violent men and vulnerable/socially-unskilled men. It is important to note that the review only includes 39 cases; therefore, these behavioural themes cannot be deemed conclusive profiles without further analysis to establish whether they are present across a wider population.

Violent/angry men: This group were typically higher security classification, had a violent offending history, higher Risk of Conviction / Risk of Imprisonment (RoC*RoI) and a greater number of incidents and misconducts, which reflects continued antisocial behaviour while in prison. They are possibly antisocial loners and may present with paranoia, or histories of reactive, impulsive violence. Previous departmental research has found at least one third of offenders with RoC*RoI scores of .70 or greater had a paranoid personality disorder (Wilson, 2004).

Vulnerable/socially-unskilled men: This group were typically lower security classification, demonstrated little or no previous interpersonal violence, lower RoC*RoI scores, and had fewer incidents, which were not predatory or violent.

Behavioural theme analysis

The two groups appear to have been viewed differently by staff and other prisoners. Staff or other prisoners did not primarily view most of the “violent/angry” group as vulnerable, rather as dangerous. As a result, they are not generally placed in ARU. If vulnerability was known, it was viewed as a secondary concern compared to their risk to staff or others. Those around the group did not generally take any physical or verbal threats of suicide seriously, and considered that the person may be venting or being manipulative.

In contrast, the “vulnerable/socially-unskilled” group were seen by others as chronically sad and high needs and not regarded as dangerous. They were possibly seen as at risk of self-harm or suicide, but not necessarily at an acute risk. The group had multiple mental and physical health issues and, as a result, the chronic nature of their presentation may have masked their acute risk of suicide.

The 2007 World Health Organisation report supports the findings of a “violent/angry” group as it notes that prison staff can sometimes view prisoners who make suicide attempts or express intent as “manipulative” (World Health Organisation, 2007). These prisoners are thought to use their suicidal behaviour to gain some control over the environment, such as being transferred to a hospital or moved to at-risk environments, or as a front for an escape attempt (Fulwiler et al, 1997; Holley et al, 1998). Some prisoners may also self-harm to reduce tension or in response to the high stress prison culture (Snow, 2002). Self-mutilation and “genuine” suicide attempts are not easily differentiated, even if the prisoner is asked about their intent (Daigle, 2006). Many incidents can involve both a high degree of suicidal intent and “manipulative” motives such as drawing attention to emotional distress or influencing management (Dear et al, 2000). Staff can take self-harm attempts less seriously when they believe prisoners are attempting to control or manipulate their environment, particularly if the prisoner has a history of past rule violations (Holley et al, 1998).

Irrespective of a prisoner’s motivation or original intent, self-harm and suicide attempts can result in death. Because of limited available methods, prisoners may choose very lethal methods such as hanging, even in the absence of a true wish to die (Brown et al, 2004). The World Health Organisation notes that when a prisoner is self-harming or expressing suicidal intent, staff should respond by trying to identify and resolve the root cause of the behaviour. Disciplining prisoners through segregation or ignoring their behaviours may worsen the problem by prompting them to take more significant risks.

Recommendations

Corrections’ primary response to the findings from the review will be addressed through a Budget 2017 initiative to develop a new model of care to improve intervention and support for at-risk prisoners. This initiative will incorporate the findings from the review and include: means of mitigating risk associated with single cells; enhanced training for prison staff in identifying at-risk prisoners; improved aftercare for prisoners transitioning out of at-risk units; and Multi Disciplinary Team support for at-risk prisoners, including prisoners managed in mainstream environments.

The review also made a number of additional recommendations. Themes from the recommendations include:

- increasing clinical consultation between health, custodial staff and psychological services staff, including improved information sharing

- developing practice guidance for health staff to ensure that prisoners who express concern about pain are re-assessed for suicidal ideation

- further analysis on Māori under-representation within prisoner suicides

- improving staff members’ ability to identify an offender’s risk of self-harm or suicide

- improving record keeping and data collation so Corrections can be more responsive to emerging trends

- further analysis of potential “angry/violent” and “vulnerable/socially-unskilled” profiles within the overall prison population

- developing a work programme to support the identification and removal of potential ligature

points across the estate where practicable.

Conclusion

The Department of Corrections is committed to reducing suicide in New Zealand prisons. As noted in the introduction, we have recently introduced a number of initiatives to address prisoners’ mental health issues and improve their quality of life.

The review aims to build on these positive steps and recommends further action to reduce prisoners’ risk of self-harm and suicide. We recognise that there are opportunities to improve our current practice and better meet the needs of all people in our care. We will learn from the past and do everything possible to help prisoners change their lives and shape a new future for themselves, their families, and our communities.

Acknowledgements

The New Zealand Department of Corrections would

like to thank the following people for their assistance and contributions to the review:

- Bronwyn Donaldson – Director Offender Health, Service Development

- Nikki Reynolds – Chief Psychologist, Service Development

- Robert Jones – Principal Analyst, Service Development

- Nick Wilson – Principal Adviser, Psychological Research, Service Development

- Deborah Alleyne – Regional Director Practice Delivery, Southern Region

- Paul Johnson – Adviser, Quality and Performance, Service Development

- Stephen Haines – Senior Psychologist

- Jill Thomson – Health Centre Manager, Otago Corrections Facility

- Ola Tupouniua-Vaka – Practice Leader.

References

Bartsch, C., Gauthier, S., Reisch, T. (2015). Swiss Prison Suicides between 2000 and 2010: Can we develop new prevention strategies based on detailed knowledge of suicide methods? Crisis 2015; Vol. 36(2) 110-116.

Beautrais AL, Collings SCD, Ehrhardt, P et al. (2005). Suicide Prevention: A review of evidence of risk and protective factors, and points of effective intervention. Wellington: Ministry of Health.

Bennefeld, K. (2012) Suizide von Gefangenen in Deutschland 200 – 2010. Nationales Suizidpraventionsprogramm [Prisoner suicides in Germany 2000-2010. National

suicide prevention programme]. Retrieved from

http://www.bildungs-institut-justizvollzug.neiderachsen.de/portal/live.php?navigation_id=24212&article_id=104837&psmand=181

Brown GK, Henriques GR, Sosdjan D, Beck, AT. Suicide intent and accurate expectations of lethality: Predictors of medical lethality of suicide attempts. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 2004, 72: 1170- 1174.

Daigle MS, Côté G. Non-fatal suicide-related behavior among inmates: testing for gender and type differences. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 2006, 36(6): 670-681.

Dear G, Thomson D, Hills A. Self-harm in prison: Manipulators can also be suicide attempters. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 2000, 27: 160-175.

Fazel, S., Cartwright, J., Norman Nott, A., & Hawton, K. (2008). Suicide in prisoners: A systematic review of risk factors. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69, 1721-1731.

Fazel, S., Grann, M., Kling, B., & Hawton, K. (2011). Prison suicide in 12 countries: An ecological study of 861 suicides during 2003 – 2007. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 46, 191-195.

Fruehwald S, Matschnig T, Koenig F et al, (2004). Suicide in custody: case-control study. British Journal of Psychiatry 185(6): 494-8.

Fruhwald, S., & Frottier, P. (2005). Comment on suicide in prison. The Lancet, 366, 1242 – 1243.

Fulwiler C, Forbes C, Santagelo SL, Folstein M. Self-mutilation and suicide attempt: distinguishing features in prisoners. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 1997, 25(1): 69-77.

Hayes, L. (2012). National Study of Jail Suicide: 20 years later. Journal of Correctional Health Care, 18, 233-244.

Holley HL, Arboleda-Flórez J. Hypernomia and self-destructiveness in penal settings. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 1998, 22: 167-178.

Joukamma, M. (1997). Prison Suicide in Finland, 1969-1992. Forensic Science International, 89, 167-174.

Konrad, N. (2002). Suicide in Haft – euroaische Entwicklungenunter Berucksichtigung der Situation in der Schweiz [Suicides in prison – European developments in view of the situation in Switzerland]. Schweizer Archiv fur Neurologie und Pschiatrie, 153(3), 131-136.

Kendler KS, Davis CG, Kessler RC (1997). The familial aggregation of common psychiatric and substance use disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey: a family history study. Br J Psychiatry, 17:541-548.

Klein, S.D., Bischoff, C., & Schweitzer, W. (2010). Suicides in the canton of Zurich (Switzerland). Swiss Medical Weekly, 140, w13102.

Le Quesne K. (1995). Suicides in prisons 1969 to 1994. Paper prepared for Suicide Prevention Working Group. Wellington, Department of Justice.

Mason, K., Bennett, H., & Ryan, E. (1988). Report of the Committee of Inquiry into procedures in certain psychiatric hospitals in relation to admission, discharge or release on leave of certain classes of patients. Wellington,Government Printer.

Metzner J, Hayes L. (2006). Suicide Prevention in Jails and Prisons. In: R Simon, R Hales, Textbook of Suicide Assessment and Management, Washington (DC), American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc, 139-155.

Ministry of Health. (1996). Policy Guidelines for Māori Health, 1996/7. Wellington.

O’Driscoll, C., Samuels, A., & Zacka, M. (2007). Suicide in New South Wales prisons, 1995-2005: Towards a better understanding. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 41, 519.

Opitz-Welke, A., Bennefeld-Kersten, K., Konrad, N., Welke, J. (2013). Prison suicides in Germany from 2000 to 2011. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 36, 386-389.

Patterson, R. F., & Hughes, K. (2008). Review of completed suicides in the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. 1994-2004. Psychiatric Services, 59, 676-682.

Rivlin A, Hawton K, Marzano L, Fazel S (2013) Psychosocial Characteristics and Social Networks of Suicidal Prisoners: Towards a Model of Suicidal Behaviour in Detention. PLoS ONE 8(7): e68944. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068944.

Sakkelliadis, E. I., Vlachodimitropoulos, D. G., Goutas, N. D., Logiopoulou, A.-P. I., Delicha, E. M., & Spiliopoulou, C. A. (2013). Forensic investigation of suicide cases in major Greek correctional facilities. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 20, 953-958.

Skegg, K., Cox, B. (1993). Suicide in custody: occurrence in Māori and non Māori New Zealanders. New Zealand Medical Journal. 106(948), 1-3.

Skegg, K., Cox, B. & Broughton, J. (1995). Suicide among New Zealand Māori: Is history repeating itself? Acta Psychiatrica Scandanavuia, 92, 453-459

Snow L. Prisoners’ motives for self-injury and attempted suicide. The British Journal of Forensic Practice, 2002, 4(4): 18-29.

Statistics New Zealand. (2017). Suicide deaths. Retrieved from http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/snapshots-of-nz/nz-social-indicators/Home/Health/suicide.aspx

White, T. W., Schimmel, D. J., & Frickey, R. (2002). A comprehensive analysis of suicides in federal prisons: A fifteen year review. Correctional Health Care, 9, 321-343.

Wilson, N. J. (2004). High risk offenders: Who are they? Report to Policy Development, Department of Corrections, Wellington. Retrieved from: http://www.corrections.govt.nz/resources/research/high-risk-offenders

Wobeser, W., Datema, J., Bechard, B., & Ford, P. (2002). Causes of death among people in custody in Ontario, 1990-1999. CMAJ, 167(10), 1109-1113.

World Health Organisation. (2007). Preventing Suicide In Jails And Prisons. Geneva. Switzerland. World Health Organisation.

1 Corrections electronic records date from 2000/2001 onwards. The rates are not age-standardised as per the national table.

2 The average female prison population was 349 in 2000/01, which translates to a rate of 286.3 per 100,000 or 22 times the rate for the general population of women that year.

3 Note that admission into custody refers to the date the case was received at prison, either on remand or recall order.