Assessing risk of re-offending: Recalibration of the Department of Corrections’ core risk assessment measure

Peter Johnston

General Manager Research & Analysis, Ara Poutama Aotearoa (Department of Corrections)

Author biography:

Dr Peter Johnston, DipClinPsych, PhD, has been with the Department of Corrections for over 30 years. He started with the Psychological Service in Christchurch as one of three psychologists who set up the first special treatment unit, Kia Marama, at Rolleston Prison in 1989. He then moved to the (then) Prison Service, where he was involved in setting up prisoner assessment centres and designing an end-to-end case management system. As GM Research and Analysis since 2004, he led a team of nine staff who undertake research and evaluation, and in-depth analysis of criminal justice data, to measure the impacts of rehabilitation, shed light on trends and developments in the offender population, and support new policy initiatives.

Introduction

Risk assessment remains a cornerstone of modern correctional practice internationally. Among a range of approaches, many correctional systems utilise actuarially-based[1] risk assessment tools in the day to day management of their Corrections systems. These assessments influence decision-making at critical decision stages of the criminal justice process, such as custodial remand, sentencing, prisoner placement, eligibility for rehabilitation programme entry, parole decision-making, and general level of monitoring and oversight in the community.

The New Zealand Department of Corrections’ actuarial risk assessment tool was developed in 1995, in a joint venture between the Department’s Psychological Service and the Maths and Statistics Department at the University of Canterbury. It was piloted over a period in the late 1990s before being implemented for general use by staff in 2001.

Known as “RoC*RoI” (an abbreviation of “risk of (re)conviction x risk of (re)imprisonment”), scores express the probability that an individual will be both reconvicted and re-imprisoned within a five-year period. For a person on a community sentence, the five-year period starts on the day the sentence starts; for a person in prison, the five-year period starts on the date of release.

The statistical equation which underpins the measure largely draws on an individual’s criminal history data, collected through their various interactions with the criminal justice system, and stored in the Ministry of Justice’s Courts Management System (CMS) database. Patterns and relationships in the data form the basis of the probabilistic predictions of future conviction and sentencing.

Over the years RoC*RoI has proven to have both high validity and considerable utility. Its validity was confirmed early on in a 2004 study that revealed very high correlations between risk scores and actual rates of reconviction and re-imprisonment (Department of Corrections, 2005). Its utility has remained evident in its continuing influence across the span of sentence management processes, particularly in sentence planning, rehabilitation programme targeting, community management, and New Zealand Parole Board decision-making.

The Department uses a straightforward three-tiered risk framework to determine the meaning of individual scores. The current risk banding is as follows:

RoC*RoI score | Risk band |

|---|---|

0.0 - 0.29999 | Low risk |

0.3 - 0.69999 | Medium risk |

0.7 - 0.99999 | High risk |

The formulation of these bands was made in the course of a major Departmental project around 15 years ago which substantially revised and enlarged the entire rehabilitative framework and the processes around it. Bands were specified in accordance with both theoretical and pragmatic considerations. However, it is noted that this framework is under current review, as international best practice with respect to correctional risk assessment favours a five-tier approach. The Department is currently considering the implications of moving to this new approach.

The need for recalibration

The accuracy of actuarial measures such as RoC*RoI is heavily dependent on the relevance of the raw data on which the algorithm has been “trained”. RoC*RoI was originally developed using conviction and sentencing data on people who had been convicted of offences punishable by imprisonment in years 1983, 1988, and 1993. It is a general truism that actuarial measures can become less accurate over time, and require recalibration using more up-to-date base data. Such a diminishment in accuracy of RoC*RoI scores has become apparent in the last decade, leading to a Departmental decision to undertake a full recalibration.

The reason for the loss of accuracy is that, over time, offending, conviction and sentencing practice (and legislation) undergo various types of change. A simple example illustrates the issue. With respect to drunk driving, Police practice, involving aggressive targeting of intoxicated drivers, combined with legislative change in the mid-2000s, made imprisonment significantly more likely for this type of offence. This in turn altered the probabilities associated with future convictions after recording one or two drink-driving convictions. Someone convicted of drunk driving in 2010 was considerably more likely to be (a) convicted of a second or subsequent offence, and (b) imprisoned for that subsequent offence, than was the case in the 1980s and early 1990s. Another example, which further illustrates the dynamic, was the advent of new community sentences in October 2007, which significantly altered the probabilities of receiving a sentence of imprisonment, relative to a community sentence, for offences in the mid-seriousness range.

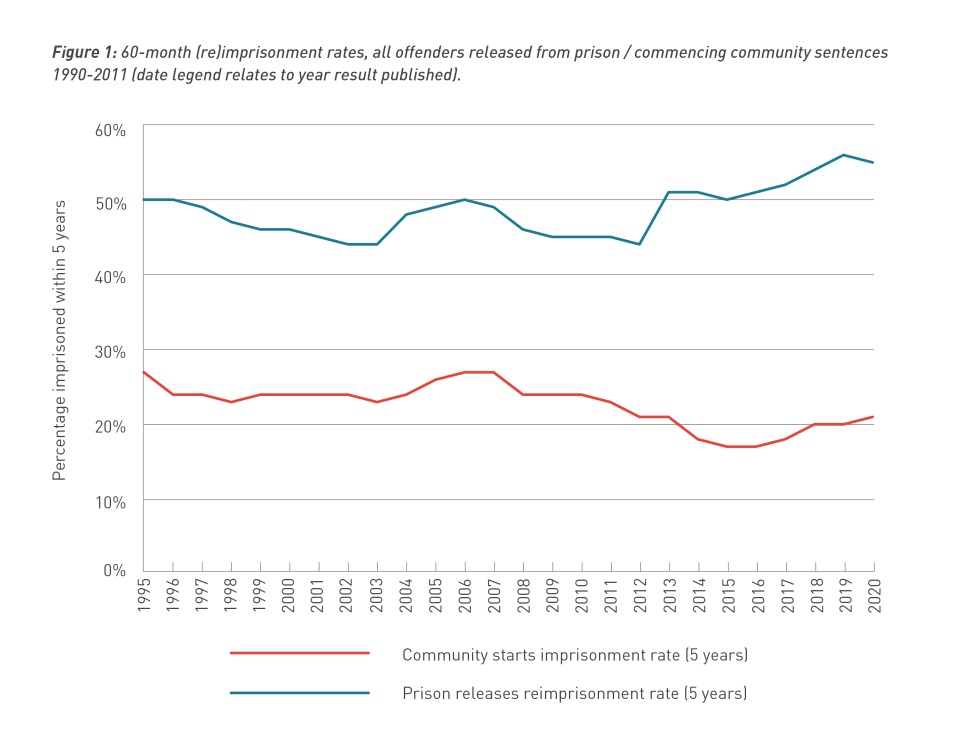

Analysis in fact shows that, while five-year imprisonment rates for community sentences have fallen over the last 25 years (and especially the last ten), re-imprisonment rates for released prisoners have remained relatively flat; since 2010, they have begun to trend upwards. This is evident in Figure 1.

Figure 1: 60-month (re)imprisonment rates, all offenders released from prison / commencing community sentences 1990-2011 (date legend relates to year result published).

RoC*RoI has been found to be remarkably accurate for prisoners over time, despite the passage of time, right up into the late 2010s. The problem of reduced accuracy was mainly for those on community sentences: correlations at group level between “predicted” reconviction rates and “actual” reconviction rates have fallen, particularly in the middle range of the risk scale. This divergence is more pronounced for certain offence sub-groups, such as burglary and driving offences. In general, the existing RoC*RoI has been found more recently to be over-estimating the likelihood of reconviction for people with community sentences. For instance, for a cohort of 100 community-sentenced people with scores between 0.4 and 0.5, RoC*RoI predicted that 45 of these individuals would be reconvicted and imprisoned within five years. The actual imprisonment rate has been about half that rate.

RoC*RoI has been found to be remarkably accurate for prisoners over time, despite the passage of time, right up into the late 2010s. The problem of reduced accuracy was mainly for those on community sentences: correlations at group level between “predicted” reconviction rates and “actual” reconviction rates have fallen, particularly in the middle range of the risk scale. This divergence is more pronounced for certain offence sub-groups, such as burglary and driving offences. In general, the existing RoC*RoI has been found more recently to be over-estimating the likelihood of reconviction for people with community sentences. For instance, for a cohort of 100 community-sentenced people with scores between 0.4 and 0.5, RoC*RoI predicted that 45 of these individuals would be reconvicted and imprisoned within five years. The actual imprisonment rate has been about half that rate.

While this situation is undesirable for a range of reasons, it is unlikely to lead to any injustices for given individuals in the community. For instance, RoC*RoI scores are not reported to sentencing judges when someone is reconvicted, thus avoiding the potential “vicious cycle” dynamic (i.e., having a higher score results in a more severe sentence; a more severe sentence further inflates the risk score; any future sentence for new offending is even more severe, and so on). Similarly, community management has no comparable decision points analogous to Parole Board decision-making, where a high risk score could, potentially, decrease the likelihood of early release. At worst, an inflated score for a community-based offender might mean that someone was expected to complete a rehabilitation programme that under different circumstances might not have been required.

It is also important to note that, over time, an increasing number of tools have been introduced to inform assessment of risk in relation to any individual. These include adoption of additional risk-related assessment tools, such as:

- DRAOR (Dynamic Risk Assessment on Offender Re-entry) – used by probation officers for on-going assessment of risk and programmes

- SDAC (Structured Dynamic Assessment for Case Management) – used by Case Management staff in prisons

- ASSIST (Alcohol and Substance Involvement Screening Test) – used to assess need for alcohol and other drug treatment

- VRS (Violence Risk Scale) – used to assess level of risk of violence re-offending

- ASRS (Automated Sexual Recidivism Scale) – used to assess level of risk of sexual re-offending.

Further, risk assessments are increasingly made with reference to positive attributes displayed by the individual, as well as the social, environmental and relationship circumstances in which they live. Greater appreciation of such additional sources of information has meant that individual RoC*RoI scores are no longer as influential as they were in previous times.

In addition, staff involved in managing sentences and orders, such as probation officers, psychologists and case managers can opt for what is known as “professional override”; this occurs in situations where relevant clinical information, which is not included in calculation of RoC*RoI, is strongly suggestive of a higher (or lower) risk level than the RoC*RoI score indicates. Override decisions are made mainly to permit entry to certain rehabilitative programmes, but can be made only when sound reasons are provided, usually generated from other risk-related tools and risk assessment perspectives.

Recalibration, and implementing the change

To ensure optimal accuracy across the board, the decision was taken a few years ago to recalibrate the RoC*RoI algorithm. This exercise was undertaken by statisticians within the Research and Analysis team of Corrections, using modelling functionality within a SAS[2] application. The data sets used for this exercise were the reconviction and sentencing histories of approximately 40,000 individuals who had either been released from prison, or who commenced a community sentence, over the 2011 year. Their combined five-year reconviction histories became, essentially, the raw material upon which the algorithm was recalibrated.

The RoC*RoI algorithm consists of around 35 highly specific variables, including sex, age at first conviction, number and seriousness of offences, length of time elapsed between offences, and length of time between prison episodes. Each of the variables has a numeric multiplier, or value, which influences the final score. The modelling process was intended to revise those numeric values; no new variables were introduced or removed. Essentially, the process sought the highest level of “fit” between possible values across the variables, and correlation with actual reimprisonment outcomes.

A review of the results indicated that changes made to the algorithm which were influential in producing shifts in individual scores, included the following:

- stronger weighting on presence of prior convictions, the seriousness of previous offending, and overall seriousness of lifetime offending

- heavier weighting on the rate of offending, such as time between the two most recent sentences

- reduced weighting on driving offences and drug offences.

Once the modelling was complete, and the highest possible degree of fit was determined, the modelling work was sent to external expert reviewers, who tested the work to determine whether it was sound, as well as to see whether further enhancements of accuracy could be achieved. Reviewers included academics from Canterbury University, and a private-sector analyst in a Wellington consultancy. These reviews confirmed the quality of the work completed, and the validity and reliability of the outputs from the recalibrated model. The university reviewer, Dr Randolph Grace, reported that the results “produced in the updated RoC and RoI models are independently replicable, and that the models' predictions are accurate”. He concluded that “… the Department can be confident that the updated RoC*RoI will provide improved risk assessment compared to the previous version” (Grace, 2018).

At this point the decision was made to implement the model across Corrections. This meant recalculating the risk score of every person currently under management, as well as using the refreshed tool with every new reception at a prison or community sentence start.

Better accuracy in risk assessment achieved through the recalibrated RoC*RoI is expected to incrementally improve the quality and efficiency of sentence management generally, for example through more accurate targeting for engagement in rehabilitation programmes, better risk management with respect to release on parole, and greater efficiency in offender management through tailoring level of oversight and controls more appropriately in relation to risk.

The implementation project was recognised as being a sensitive matter especially as, for some prisoners, a change in score might also mean a change of risk band (e.g., if a score changed from 0.75 to 0.65, the individual concerned would technically, no longer be “high-risk” but instead “medium-risk”). Careful planning was undertaken to ensure that any individuals subject to such changes were individually assessed and managed to minimise disruption to their current management, and to ensure procedural fairness.

At time of writing (February 2021), the implementation of the recalibrated RoC*RoI is proceeding well; ongoing monitoring and feedback is being sought but no significant issues have been identified, or complaints from prisoners or offenders on community sentences received.

Algorithms and the public sector

Concurrently with, but independently of, the process of recalibrating the RoC*RoI, Statistics New Zealand launched a review of algorithm use across the public sector. This review responded to growing concerns internationally that algorithms can have unintended adverse effects for some sub-groups within populations. Particular concern exists in relation to their potential to perpetuate bias against minority groups. Such concerns have arisen also in relation to correctional risk assessment tools, particularly when the results of such assessments are used in sentencing decisions (which, as noted above, is not a practice in New Zealand). This can come about for instance as a result of police racial profiling in pursuit of people suspected of crimes, leading to higher arrest and imprisonment rates for minority groups. These higher conviction rates then translate to higher risk scores, which can then, in a court sentencing situation, lead to more severe sentencing. NZ Police have in fact recently acknowledged that bias has affected their front-line practice.

A similar issue was tested some years ago when the Department’s use of the RoC*RoI algorithm for offender management purposes was scrutinised in a Waitangi Tribunal hearing (WAI1024 [2005] The Offender Assessment Policies Report[3]). The tribunal concluded that the Department’s failure to consult adequately with Maori during the development of the RoC*RoI tool was “plainly inconsistent with Treaty principles”, however, in terms of the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975, the Tribunal found it had “not been established that prejudice flows from the operation of RoC*RoI” (pp 129-130).

The main outcome of the Statistics New Zealand review is the production of an “algorithm charter”, which commits agencies to abide by certain principles of use in relation to these tools. The Department of Corrections is currently preparing to sign the Charter. The following outlines the principles of the Charter, and the ways in which the Department has, or intends to, conform its practice to them, in relation to RoC*RoI.

Principle 1: Clearly explain how decisions are informed by algorithms

The Department regularly responds to enquiries, often made under the OIA, on how its offender management decisions are made, including the influence of risk data on such decisions. Front-line staff are trained in the preparation of reports which include risk data, and can thus explain to the person concerned how risk information is used in recommendations. An article for publication in a peer reviewed journal is currently under preparation which will document the recalibration of Roc*RoI and its increased levels of accuracy; this article will also explain how offender management decisions are informed by RoC*RoI.

Principle 2. Embed a Te Ao Māori perspective in algorithm development or procurement

In order to minimise the potential for bias, ethnicity is not a variable within the RoC*RoI algorithm. Nevertheless, the tool performs very well in terms of accuracy in assessing risk of re-offending amongst Māori. We are committing to on-going review and recalibration in the future to ensure that the tool remains optimally accurate for Māori. In addition, we have invited Māori academics to advise us, both on any risks associated with the use of the tool with Māori, as well as to monitor the on-going implementation of the revised tool.

Principle 3. Focus on people, identifying and engaging with groups or stakeholders with an interest in algorithm development

Staff involved with the recalibration exercise are already engaging with external stakeholders, especially New Zealand academics, who have an interest in algorithms, such as the Law School at Otago University.

Principle 4. Make sure data is fit for purpose

The data which informs the risk scoring comes from core sector and departmental systems with rigorous processes for ensuring accuracy, especially in relation to the key variables. The recent recalibration modelling and testing described above is entirely based on validating, to the highest degree possible, the scores on the measure, with the predicted outcomes (i.e. rates of reimprisonment).

Principle 5. Ensure privacy, ethics and human rights are safeguarded

Our recalibration project has involved extensive expert independent peer review and validation of the methodology. Staff within the Research and Analysis team at Corrections are available to manage and respond to enquiries from interested parties who wish to understand how the method works. We also maintain involvement with current public sector working groups with an interest in algorithm safety and ethical soundness.

Human rights are also protected though rights of legal challenge to decisions made by judicial bodies where RoC*RoI scores may play a part in deliberations (e.g. parole release).

Principle 6. Retain human oversight

A good example of this is the way in which RoC*RoI scores are treated as simply one of a number of considerations used by the NZ Parole Board in making decisions about release. Further, in relation to another important way in which RoC*RoI is used – as a determinant of programme eligibility – we have the facility for professional over-ride, which essentially is the application of human oversight to such decisions.

Conclusion

The NZ Department of Corrections remains committed to best practice in delivering correctional management. Risk assessment remains a cornerstone of that practice, and the RoC*RoI tool is central to our risk assessment methods. The recent recalibration exercise demonstrates our commitment to ensuring that the tool is optimally accurate and, as a result, our practice is as informed, targeted and effective as possible.

References

Department of Corrections (2005). Annual Report 2004/05; available at http://corrnet.corrections.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/176228/ar2005-part1-strat-context.pdf

Grace, Randolph, (2018). A revised RoC*RoI model to predict risk of recidivism for offenders released from community and prison sentences. Unpublished report prepared for Department of Corrections.

Ministry of Justice (2005). The Offender Assessment Policies Report; available at https://forms.justice.govt.nz/search/Documents/WT/wt_DOC_68001752/Offender%20Assessment%20Policies.pdf

[1] Actuarial tools in the correctional domain typically rely on criminal history data at the individual level which is then processed via an algorithm to produce a risk score, valid for that person, at that time in their life, which in turn signifies probabilities of a specific outcome, such as re-offending leading to reconviction or reimprisonment within a certain time frame.

[2] SAS is a sophisticated statistical package, used under license.