Intervention and Support Project

Rachel A. Rogers

Senior Adviser, Mental Health, Ara Poutama Aotearoa (Department of Corrections)

Shelly Reet

Principal Adviser, Mental Health, Ara Poutama Aotearoa (Department of Corrections)

Joanne Love

Senior Adviser, Mental Health, Ara Poutama Aotearoa (Department of Corrections)

Author biographies

Rachel started work for Corrections in August 2017 as Senior Adviser for the Intervention and Support Project. Her background is in community safety and emergency management. Rachel has worked in the Victorian Fire Service and New Zealand local government in a range of hands-on and managerial roles. Rachel has an MA in Psychology focused on behaviour modification, as well as post-graduate diplomas in community safety, and emergency management. Rachel is currently Senior Adviser on the Mental Health Quality and Practice Team.

Shelly is the National Principal Adviser on the Mental Health Quality and Practice Team, and has over 35 years’ experience in the mental health and social services sector in a range of senior leadership and management roles. She holds a Master of Science in Mental Health, Post graduate Diploma in Management, Advanced Certificate in Adult Education, and is currently studying for a post graduate qualification in Professional Coaching.

Joanne started work for Corrections in September 2017 as Clinical Adviser for the Intervention and Support Project. Her professional background is mental health nursing, having worked in crisis teams, as a police watch house nurse, a clinical nurse specialist and in psychiatric liaison roles. Her Master of Nursing thesis was around the recognition by police officers of mental illness in detainees.

Introduction

It is well established in international and New Zealand literature that a higher prevalence of mental distress occurs among prisoners compared to the general population, particularly psychosis, major depression, bipolar disorder, and substance dependence / misuse. Furthermore, people subject to custodial care identified as at risk of suicide or self-harm have significantly higher rates of clinically significant symptoms of mental illness, as measured by a standardised instrument, than the general population (Senior et al, 2007).

In some instances, being in custody can create or precipitate mental health difficulties and heighten the risk for those who are susceptible to self-harm and suicide.

Globally the rate of suicide in prisons is between three to nine times higher than that in the general population (Martin et al, 2014), with some studies reporting it as much as 15 times higher (McArthur, Camilleri and Webb, 1999).Relative to the New Zealand community rates standardised by age band, sex and ethnicity, annual prison suicide rates here are up to three times higher (Mental Health Foundation, 2020)[1].

Early identification of, and intervention with, someone at risk of self-harm or suicidal behaviour has the potential to reduce the need for more intensive and more expensive approaches, such as forensic inpatient services, later in a person’s time in prison. As such our focus moved beyond just the immediate safety of at-risk prisoners to creating a therapeutic, needs-based approach for at-risk prisoners, adopting a graduated, multi-disciplinary response focused on intervention and support.

Background

In 2016-17 the Intervention and Support Project Team undertook a series of literature reviews, qualitative interviews and site visits to investigate self-harm, suicide, and the management of these conditions within prisons. The intent was to determine the themes that needed to be addressed when creating a model of care[2] (the model) for people vulnerable to self-harm and suicide.

Key themes from the research were factored into the model’s design (Department of Corrections, 2019a). These included:

- incorporating a te ao Māori worldview

- the importance of a robust mental health screening and triage process

- use of a “stepped care approach” in the treatment of mental health issues

- individualised care plans

- increased information sharing pathways

- improved physical environments

- more opportunity for building social connections

- a strong multi-disciplinary approach.

Māori have their own worldview of what constitutes health and wellbeing. A key difference discussed by McNeill (2009) between Western and most Māori models of health is that Māori models include a spiritual component. It is this spiritual component which becomes particularly important in the field of mental health.

Reduction of stigma and discrimination, improving resilience of both staff and those in our care, the physical setting, and expanding health literacy were identified as key to building a more therapeutic environment.

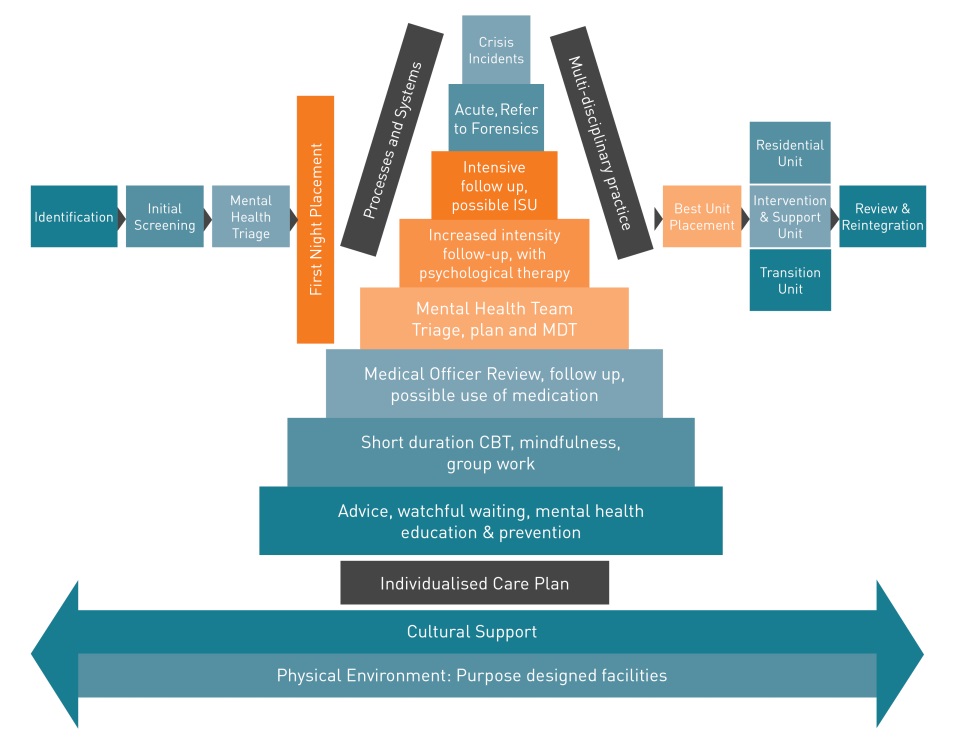

The high-level design for the model (see Figure 1) was approved in April 2017 and provided the basis for development of the detailed components which underpin the approach.

The model takes a “whole of prison” approach to people in the care of Ara Poutama Aotearoa who are vulnerable to self-harming behaviour or suicide, through:

- identifying those who need support earlier in their sentence

- improving people’s experience of mental health services

- empowering those in need to identify and manage their own stress

- streamlining some business processes to support timely referral and intervention

- increasing staff capability through education and skills development

- progressing the development of an evidence based multi-disciplinary practice.

The model was piloted in three prisons: Christchurch Men’s Prison, Auckland Prison, and Auckland Region Women’s Corrections Facility.

Figure 1: Transforming Intervention and Support for people in prison vulnerable to suicide and/or self-harming behaviour (high level design)

Model of Care

The detailed specifications of the model expanded on the high-level design, in order to operationalise the approach.

Intervention and Support practice teams

A specialist Intervention and Support Practice Team (ISPT) has been introduced at each of the pilot sites. Each team includes:

- a clinical manager mental health

- psychologists (working with a clinical or counselling scope of practice)

- clinical nurse specialists – mental health

- an occupational therapist

- a clinical social worker

- a cultural support worker.

The clinical team is supported by an administration officer and two dedicated custodial officers.

The ISPT leads health and custodial staff in the delivery of services in the Intervention and Support Unit (ISU). This includes assistance with care and treatment planning and transition back to mainstream units. Structured support is also provided to those individuals in mainstream who are vulnerable to suicidal or self-harming behaviour.

Recruitment for the ISPTs commenced in April 2018, well in advance of completion of the service design; this long lead-in was planned in recognition of the international shortage of mental health professionals.

A shortage of mental health professionals was not the only challenge encountered. Site change leads were appointed at each site to support the pilot sites to prepare for and embed the new model of care into “business as usual” practice. However, operational realities often diverted their focus to other business requirements.

Given the recruitment difficulties, a phased service implementation approach was adopted, aimed at providing a clinically and culturally safe, individualised service in the ISU based on the recruited staff member’s professional scope of practice. As more staff were recruited, the service was extended beyond the ISU to support the wider prison. The approach identified the minimum number of ISPT members who needed to be in place at each phase of implementation, requirements to support each phase, and the components of the model able to be delivered within a safe clinical framework.

Screening

Suicidal or self-harming behaviour is routinely screened in prisons using an abbreviated version of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). This is done by custodial staff as part of the reception risk assessment, and the review risk assessment.

To strengthen the identification of those most vulnerable, an additional assessment for those who screen positive, or for those who health centre staff or custodial staff have concerns about, has been added.

A member of the ISPT who is a registered mental health professional undertakes a comprehensive clinical assessment and mental status exam, within 24 hours of intake. A suite of additional assessment tools has been assembled for this purpose.

A member of the ISPT who is a registered mental health professional undertakes a comprehensive clinical assessment and mental status exam, within 24 hours of intake. A suite of additional assessment tools has been assembled for this purpose.

Following the clinical assessment, the ISPT clinician determines the level of risk of each individual. If deemed low risk, the receiving officer completes the induction process with the person and they are placed in a mainstream unit.

A cultural assessment framework was developed to support the cultural support workers to:

- work with people with mental health needs, including those vulnerable to self-harming behaviour or suicide, to encourage and build relationships/connections with their family/whānau and their communities

- initiate, organise and collaborate with staff involved in the care of people with mental health needs to increase awareness of staff knowledge of Māori culture to better monitor progress and provide additional support where required

- provide cultural assessment and treatment reports for those under the care of the ISPT

- advise and assist the ISPT multi-disciplinary team to ensure treatment, activities and programmes are appropriate to the cultural and mental health needs of individuals.

Post screening triage

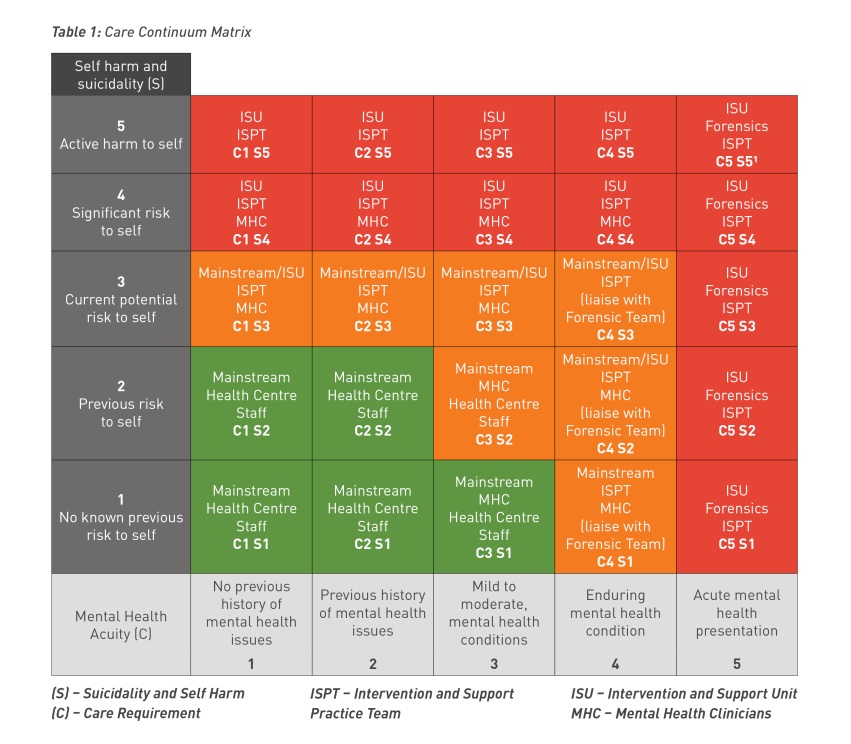

A post screening triage tool called the “Care Continuum” is applied to all those assessed as vulnerable to suicide or self-harm following the clinical assessment. The Care Continuum matrix is shown in Table 1.

The Care Continuum tool combines the risk of self-harm and suicidality with the level of mental health acuity to indicate the best placement and support decisions for the person, including:

- the prison unit most suitable for placement

- the level of mental health support required

- identification of the lead clinician for provision of support, and

- initial care actions.

The placement decision may result in transfer to the ISU, to hospital, or to a residential unit (with or without specific recommendations for support) or to a first night or transition unit (where available).

Guidelines on the use of the Care Continuum have been developed (Department of Corrections, (2019b). Based on best practice, the Care Continuum offers staff a common “language” that does not disclose sensitive health information, thereby addressing some concerns around privacy. This was successfully trialled in Christchurch Men’s Prison.

Table 1: Care Continuum Matrix

Intervention and Support unit

Those individuals at immediate risk of self-harm or suicidal behaviour (“active harm” or “significant risk”), or those with acute mental health needs, and thus awaiting transfer to hospital or forensic in-patient mental health care, are placed in the ISU.

People transferred to the ISU outside of ISPT working hours have an initial care plan developed and maintained by custodial staff, until such time as the ISPT can assess them and the multi-disciplinary team can identify a key clinician.

Transition unit

Once assessed, those new to prison are placed in a “first night” or reception/transition unit where close monitoring and support are available.

Unless there is concern about the individual’s vulnerability, or risks of victimisation, self-harm, or suicide, a first night unit is the preferred option and has the additional benefit of stigma reduction.

Intervention and Support care plan

A needs-based individualised care plan is completed for each person under the care of the ISPT, whether they are housed in the ISU or not. It is completed after the clinical and cultural assessment. The risk formulation developed through the clinical assessment informs the focus of the care plan.

The care plan specifies the practical support strategies that custodial staff, mental health clinicians and health staff can all use. Care plans are developed in consultation with appropriate support personnel, with input from health services medical staff, specialist ISPT cultural advisers and whānau. Whenever possible, the person under the care of the ISPT contributes to the development of their own plan. While some people accommodated in an ISU may initially need staff to determine what is best for them, others are quite capable of contributing.

A multi-disciplinary team meeting is convened to ensure the plan is tailored to individual needs. For each person in our care there is a custodial lead, as well as a key clinician. The key clinician is identified at the multi-disciplinary team meeting and is responsible for ensuring the care plan is implemented and updated as needed.

The key sections of the care plan are:

- a wellness plan which is completed by the person in care to provide information on “what distress looks like” for them, their triggers, and what others ought to do in response

- the clinical aspects of assessment and treatment (including cultural, health and other services)

- a custodial management strategy, including decisions around locking and unlocking, association, and meals.

Review processes

An individual’s vulnerability to suicide or self-harm must be reviewed when there are any significant changes, including changes in their custodial status, whānau circumstances, health status, a transfer, or if an individual begins to display changes, either positive or negative, in mood or behaviour.

The Review Risk Assessment must be completed within four hours of staff being advised of any of the above events and be conducted by trained custodial staff in a private location. If there are any concerns about a person’s vulnerability to suicide or self-harm, custody staff must notify the ISPT.

If there is a delay between the event that warrants a Review Risk Assessment and the assessment taking place, the individual will be treated as vulnerable and placed under observation not exceeding 15 minutes intervals, until the Review Risk Assessment can begin.

The review of circumstances for individuals already under the care of the ISPT is managed as per their care plan.

Service exit criteria

The services for an individual under the care of the ISPT come to an end when one or more of the following criteria have been achieved:

The individual:

- is successfully self-managing their mental health needs

- has accomplished the ISPT-related goals set out in the care plan

- has been referred to other mental health services and no longer requires ongoing support from the ISPT

- has left prison and been referred to a community provider.

No individual under the care of the ISPT is transferred between prisons without consultation and approval from the ISPT clinical manager mental health.

The ISPT clinician completes formal discharge/handover advice to the receiving agency and makes any follow-up recommendations if appropriate.

Implementation Approach

The model is a transformational change in practice for Ara Poutama Aotearoa. In recognition of the size and scale of the change, support was provided to pilot sites through change management activities. This included targeted communications and training to prepare staff for the implementation of the new model, and support to successfully embed it into “business as usual” practice.

A staged implementation of the model was planned on a site-by-site basis; reflecting the recruitment build up and specific requirements for that site.

Implementation at Christchurch Men’s Prison began in August 2019 with practice focused on delivering services in the ISU. As additional members of the team were appointed, the implementation approach assumed that the service would expand to deliver across the prison, beginning with mainstream units, then into the Receiving Office. However, a review was undertaken after three months to assess the site’s readiness to move to the next stage of implementation.

Outcomes of Christchurch Review

The review highlighted a number of issues that impaired the team’s ability to deliver the treatment and care as was envisaged. A number of key recommendations were made as a result, including:

- the need to acquire additional space within the site for meetings and consultations

- an increase in the number of ISPT team members to meet the level of demand

- the need to adopt a wider range of assessment tools

- increased levels of cultural support needed to support the wider site

- generally broadening the scope of the model of care to encompass mental health needs beyond suicide and self-harm.

The “go live” date for the implementation at the two Auckland sites was delayed to accommodate the learnings from the Christchurch Review. Unfortunately, this new date was further delayed due to the emergence of COVID-19 in early 2020. However, by April 2020, the two teams were operating at the Auckland sites with the recommendations from the Christchurch Review incorporated into practice. An operational guideline was then co-produced to ensure that cultural and clinical practice aligned at all three sites.

Between July 2020 and February 2021, the three teams have worked with over 500 individuals. At the time of writing (March 2021), there are 185 active cases, with each clinician managing between five and fourteen cases at any one time. The reasons for referral vary between the sites but include suicidal and/or self-harming behaviour, trauma, personality disorders and psychotic disorders.

Changes in ISUs in Non-Pilot Sites

As well as the introduction of the clinical teams at the three pilot sites, in June 2018, the project’s scope was extended to include some activities being rolled out to non-pilot sites. This followed a national Intervention and Support Learning Event held in April 2018 that introduced new tools and techniques to improve management of those vulnerable to self-harm or suicide. The enhancements included renovations to the therapeutic environments of ISUs such as painting, furniture and equipment, as well as:

- a supported decision-making framework (SDF) for staff in ISUs

- guidelines for working in a multi-disciplinary teams

- renaming of At-Risk Units to Intervention and Support Units

- sensory modulation training and resources.

Next steps

Ara Poutama Aotearoa is currently (2021) developing a mental health and addiction service at three prison sites (Rimutaka, Waikeria, and Mount Eden). An additional eight prison sites will be provided with a clinical nurse specialist (mental health) role reporting to the health centre manager, further supporting the specialist mental health response on each site.

Suicide prevention training for staff is being delivered at four sites initially, and a training package is being developed to roll out to other sites. This training is for frontline prison staff including custodial staff, case managers, and health staff, with the initial focus on custodial staff in the ISUs.

Clinical supervision is currently being rolled out for custodial staff in ISUs. Clinical supervision and support for these staff is vital because they are at the “sharp end” of managing some of the most vulnerable people in our care.

A Suicide Prevention and Postvention Group has been established to oversee research, analyse relevant data, and provide advice on prevention and management of suicide and self-harm. Ara Poutama Aotearoa is developing a Suicide Action Plan aligned to Every Life Matters – He Tapu te Oranga o ia Tangata[3].

Ongoing support for the Intervention and Support Project has been integrated into business as usual for the Mental Health Quality and Practice Team at Corrections National Office. Part of this support will include the development of a peer support programme for those in our care, and a move towards a single point of entry for all mental health needs.

References

Agency for Clinical Innovation (2013). Retrieved from https://www.aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/181935/HS13-034_Framework-DevelopMoC_D7.pdf#zoom=100

Department of Corrections (2019a). Intervention and Support Project: Intervention and Support Detailed Design.

Department of Corrections (2019b). Intervention and Support Project: Guidelines to using the Care Continuum: Intervention and Support Pilot Sites.

Martin M., Dorken, S., Colman, I., Mckenzie K., Simpson A. (2014). The incidence and prediction of self-injury among sentenced prisoners. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 59(5): 259-267.

McArthur, M., Camilleri, P., Webb, H. (1999). Strategies for Managing Suicide & Self-harm in Prisons. Trends & Issues in Crime & Criminal Justice. Aug 1999, Issue 125.

Mental Health Foundation (2020). Annual provisional suicide statistics for deaths reported to the Coroner between 1 July 2007 and 30 June 2020. Available at https://www.mentalhealth.org.nz/assets/Suicide/2020-Annual-Provisional-Suicide-Statistics.pdf

Ministry of Health (2019). Every Life Matters - He Tapu te Oranga o ia Tangata: Suicide Prevention Strategy 2019–2029 and Suicide Prevention Action Plan 2019–2024 for Aotearoa New Zealand. Wellington: Ministry of Health.

Senior, J., Hayes, A.J., Pratt, D., Thomas, S., Fahy, T., Leese, M., Bowen, A., Taylor, G.,

Lever-Green, G., Graham, T., Pearson, A., Ahmed, M., Shaw, J. (2007). The identification and management of suicide risk in local prisons. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology. Sep 2007, Vol. 18 Issue 3, p368-380.

[1] The Mental Health Foundation report indicates 2019/20 rates of suicide nationally for males aged between 20 and 50 years at between 22 and 34 per 100,000; the comparable average annual rate amongst prisoners (last five years) was 58 per 100,000.

[2] A Model of Care describes the way health services are delivered. It outlines best practice in care and services for a person as they progress through stages of health or illness (Agency for Clinical Innovation, 2013).