Case study: How prototyping was used to design the solution for photographing people in the care of the Department of Corrections in the community

Irene Keane

Manager Design and Implementation, Service Development, Department of Corrections

Author biography:

Irene has been with the Department of Corrections for ten years in a number of different roles. Currently she works in Service Development, supporting the design and implementation of new initiatives. She is passionate about ensuring that what is designed and implemented meets the needs of users.

Introduction

The Enhanced Identity Verification and Border Processes Legislation Act (2017) enables the Department of Corrections (Corrections) to collect biometric information from offenders serving community-based sentences and orders. The legislation defines the types of biometric information that can be collected and includes a photograph of all or any part of the person’s head and shoulders. Prior to the enactment of this legislation Corrections could only take photographs for the purposes of managing prisons.

This case study demonstrates how design thinking was used to develop the solution for capturing and managing photographs of people in the care of Corrections in the community.

Design thinking and prototyping

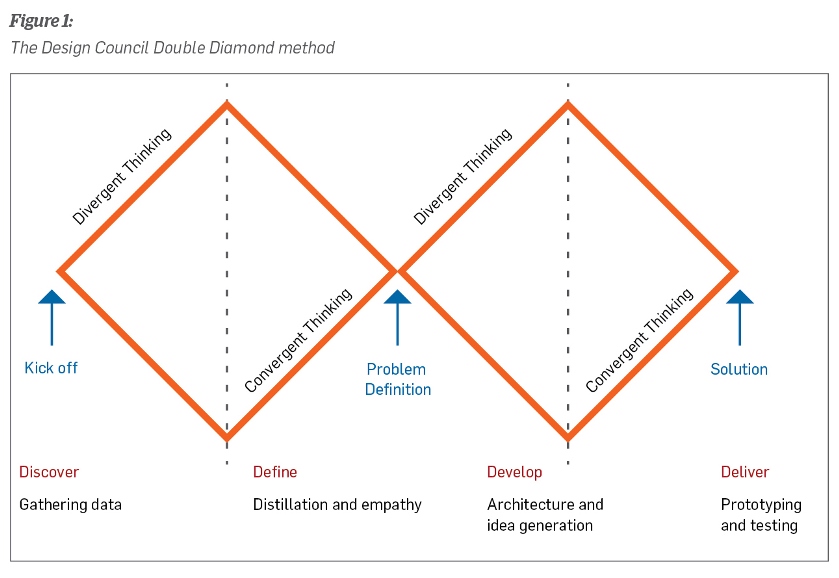

Design thinking is by definition exploratory: solutions are developed, prototyped and tested using iterative, “safe-fail” experiments to gain rapid feedback. The Double Diamond method developed by the Design Council[1] is well known and a widely recognised way to deploy design thinking.

As Figure 1 illustrates, the Double Diamond method helps to uncover a problem by using a collaborative and iterative approach, and then re-engaging in divergent and iterative thinking to arrive at a solution. The process does not commit at the outset to the form of an end solution but rather generates ideas that could ultimately become physical or digital products, services or processes (Conway, Masters and Thorold, 2017).

The design workshop

Staff from a number of roles came together for a design workshop facilitated by an external provider. At the workshop the Double Diamond method was used to explore how Corrections could capture and manage photographs of people in our care in the community.

With the processes, tools and technology already available in all prisons this could appear simple – merely a case of implementing the existing capabilities into each location in the community. However, as the group undertook the Discover Phase of the Double Diamond method and gathered information, it quickly became apparent that the issues were more complicated.

For example, the group explored the following questions: Why does the photograph exist? Where does it live? When is it created? How is it created? Where is it created? How is it seen? Who is able to access it? How “perfect” does the photograph need to be? How is it validated? Who owns the photograph? When is it deleted?

Design thinking tools and techniques were then used to distil this information and to move through the Define and Develop phases of the model. A number of ideas and paper prototypes were developed for:

- obtaining and validating the photograph, including metadata and any other available biometric data

- managing and sharing a photograph including metadata and the need to share access to the records

- verifying identity from a photograph manually against other documentation or automatically if available.

These prototypes were then presented to a group of senior stakeholders for challenge, feedback and prioritisation for development. It was agreed that the first priority was to focus on developing a solution for how the photograph would be taken and validated.

Numerous potential sources of photographs were identified including:

- using a photograph that had been taken in prison

- asking a third party such as Police, Department of Internal Affairs or Immigration to provide the photograph

- asking the offender to provide their own photo, such as one taken for a passport, driver licence, or RealMe

- using a staff-held cell phone or camera to take the photograph during induction to a sentence or order, or on a home visit

- installing a wall-mounted fixed camera in a meeting room for taking a photograph during induction to a sentence or order at a Community Corrections site

- using a ceiling-mounted camera or CCTV for taking the photograph.

Each source of photograph had complexity and may not have provided the quality of image or a current version that was suitable for the identified purpose of recording and verifying the identity of the offender.

Workshop participants considered that the most straightforward option was for Community Corrections to use the same system as a prison; a fixed camera with the photograph stored in the offender information management system. Community-based staff could add a photograph taken during induction to a community sentence or order or when a person’s appearance changed significantly. This option would remove systems integration costs, challenges and risks, and make it easier to manage the quality, usage, and future enhancements. A fixed camera was preferred to reduce the safety risk, maintain quality, and make it as simple as possible to use. However, it was thought that there may be some situations, such as shared office locations, where a hand-held device may be required.

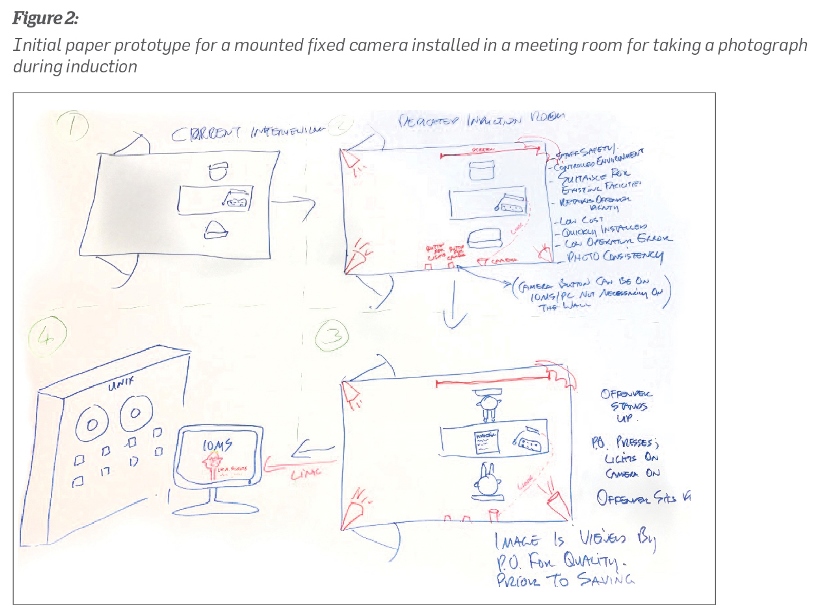

A paper prototype (see Figure 2) to confirm the business requirements and process at Community Corrections sites was selected for testing and further development.

Testing the prototype

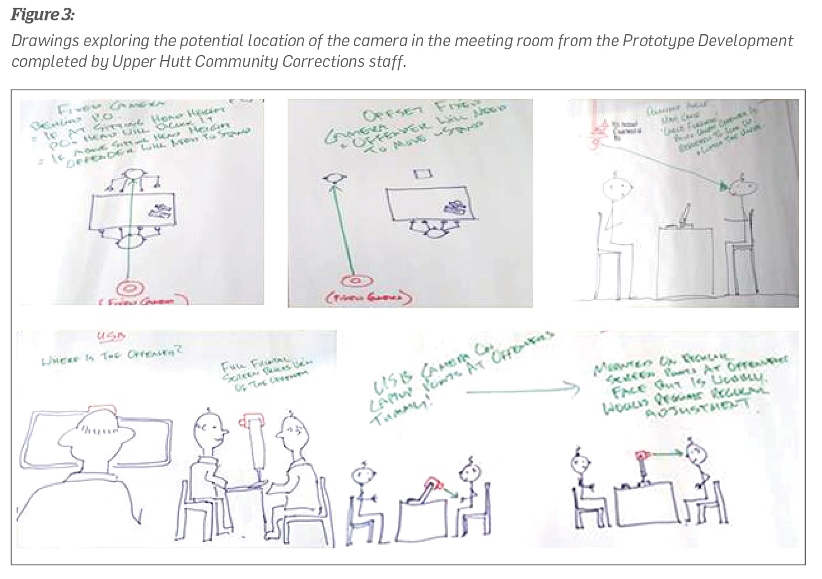

Over the following month the team at Upper Hutt Community Corrections undertook research, role plays and workshops to test and further develop the initial paper prototype. Figure 3 shows some of the output from the role plays and workshops exploring the location of the camera in the room.

As testing progressed the focus moved from a camera set-up (Figure 4) that would be safe and best suit the way staff work to the engagement and discussion with the person whose photograph was being taken. This included identifying tools such as hand-outs and extra information to be included in the induction pack, practice guidance such as step-by-step instructions and advice on how to take a good photograph, guidance on what to say if the person refuses to be photographed or questions the legality of taking photographs, and the support staff needed for this engagement to be successful.

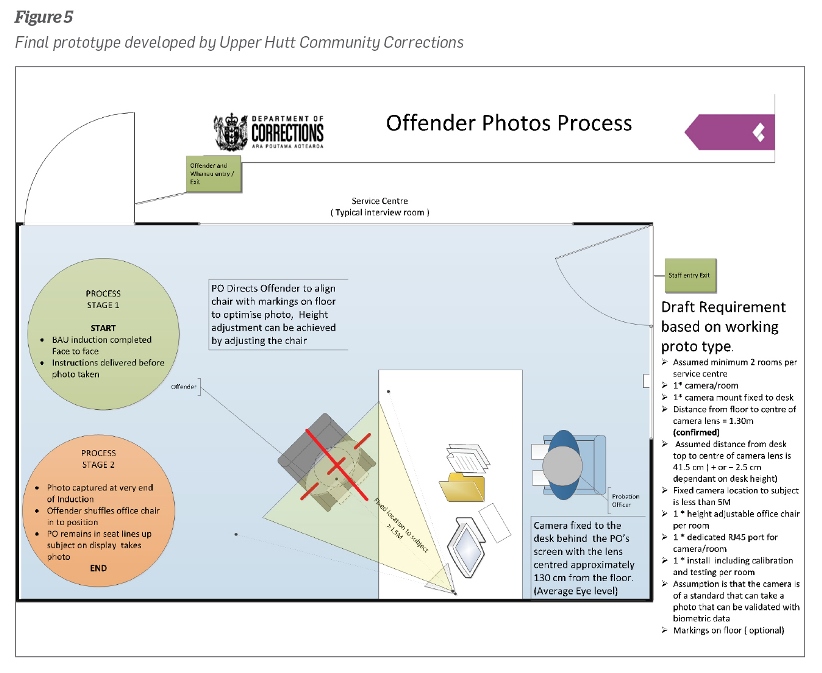

Working in this way enabled the staff to quickly test ideas and refine the prototype. The staff confirmed the most efficient and safe way of taking photographs involved taking the photographs at the end of induction with a fixed camera. However, their testing resulted in significant changes to the prototype (Figure 4), in particular the set-up of the room.

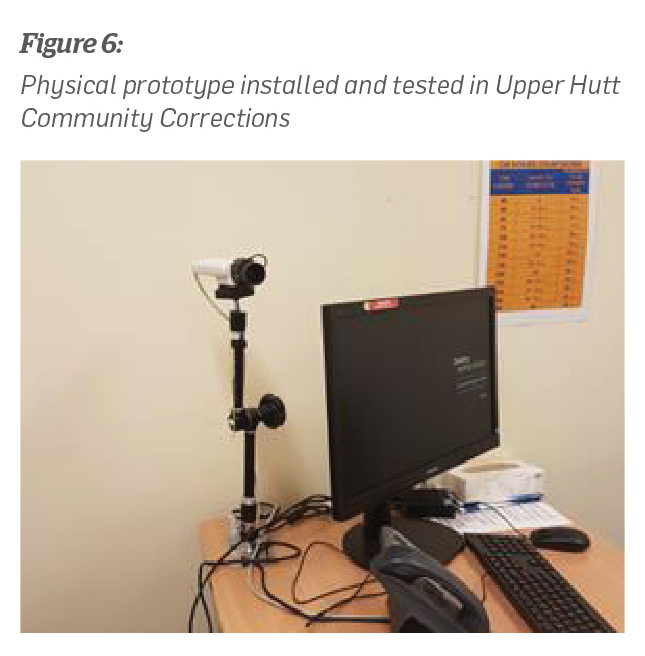

It was at this time that the first physical prototype was installed in an interview room at Upper Hutt Community Corrections (Figure 6) and the team started taking photographs of the people in our care. This prototype had limited integration with technology systems and allowed for further testing of the solution, including the process for taking photographs, tools and practice guidance, before investing significantly in changes to our technology systems. No changes were made as a result of this testing and a decision was made to introduce the prototype in a phased way, starting with five additional sites. Work also began on integration with technology systems.

The physical prototype went through two further iterations as part of the phased introduction.

Integration issues with technology systems have resulted in changes to some hardware and software elements of the design. These issues have been addressed incrementally during implementation and have not impacted on the experience of staff or the people in our care.

Summary

We found that prototyping results in a practical understanding of the issues, challenges and opportunities that will be faced by users very early on in the design process. Issues and challenges were tested, addressed and resolved as they arose, with unworkable options and problems eliminated from the design long before they negatively impacted on budget and timelines. The iterative approach gave maximum value for relatively small cost and avoided locking the organisation into an expensive solution that may or may not meet future needs.

Practice guidance, tools and resources to support implementation were developed and tested by staff themselves as part of the prototyping process. As a consequence we found that some of the traditional barriers to change were removed. We found that when our staff were actively involved in the prototyping process, the solution had high credibility amongst their peers; staff had strong confidence that the solution addressed practice and safety concerns and would be implemented in a way that met their operational needs.

The Department of Corrections continues to look for opportunities to use prototyping as part of solution design and to develop it further.

[1] The Design Council, formerly the Council of Industrial Design, is a United Kingdom charity incorporated by Royal Charter. It is recognised as a leading authority on the use of strategic design. They use design as a strategic tool to tackle major societal challenges, drive economic growth and innovation, and improve the quality of the built environment. Their approach is people-centred and enables the delivery of positive social, environmental and economic change. They address all aspects of design including product, service, user experience and design in the built environment. They are the UK government’s adviser on design. Further information can be found at https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/.

References

Conway R., Masters J., Thorold J. (2017) From Design Thinking to Systems Change - How to invest in innovation for social impact RSA (Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce)