Update on the community-based two-year alcohol and other drug testing trial

Nyree Lewis

Principal Practice Adviser (Acting)

Case Management and Probation Practice Team, Department of Corrections

Author biography:

Nyree joined the Department of Corrections in 2010 as a probation officer. Since then she has been a practice leader, senior practice adviser and is currently acting as Principal Practice Adviser. Nyree has a passion for probation practice and uses her experience in the field to help continuous improvement in this area.

Introduction

This article provides an update to a previous article (Lewis, 2018) which gave the early results of a two-year Northern Region trial of alcohol and other drug (AOD) testing in the community. The testing is of people with an abstinence condition (imposed by a court or the New Zealand Parole Board) who are serving a community-based sentence or who are subject to Police bail.

The trial will finish on 30 June 2019. However, a final evaluation was completed in April 2019. In addition, two earlier process evaluations and a practice audit have supplied interesting findings which are also presented in this article.

Background

The trial began on 16 May 2017, the day the legislation was enacted to allow for the testing of this cohort. Previously, legislation had not provided clear authority to test people serving a community-based sentence/order, or those on bail, even when they were subject to an abstinence condition.

The trial aims to increase monitoring and accountability for people with abstinence conditions in the community. The Department of Corrections expects the testing and monitoring will lead to:

- reduced alcohol or drug use amongst people with abstinence conditions

- improved compliance with conditions of sentences and orders, and bail

- improved engagement with rehabilitation services

- reduced harm caused by alcohol and other drug misuse through a change in the rate of offending

- individual health benefits.

Corrections and Police are trialling several technologies to test people for alcohol and drugs. These include:

- urine testing for drugs and alcohol (conducted on a randomised basis and where there are reasonable grounds, as shown in Table 1)

- breath alcohol testing (BAT) of bailees and of specific people on a sentence/order

- alcohol detection anklet (ADA) monitoring for a small number of people who are at a high risk of causing harm if they consume alcohol.

Corrections is also trialling a triage process for choosing whom to test and at what frequency. An automated tool selects the tier a person is placed on based on their static factors such as risk and sentence type, but the probation officer can use their professional judgment to override this tier based on other factors known about the person and their circumstances. More information about the tiers is outlined in Table 1.

Table 1:

Corrections/Police AOD testing trial risk bands and testing tiers

AOD Testing Tier | Risk Band | Description of Testing Methods for Corrections Offenders | Description of Testing Methods for Police Bailees |

|---|---|---|---|

Tier 1 | Lower priority offenders | “Reasonable grounds” testing. | Police will use their own risk-based management practice with bailees. ALL defendants on bail with an abstinence condition will be subject to reasonable grounds testing. |

Tier 2 | Medium priority offenders | Random testing at a lower probability than Tier 3. They are also subject to reasonable grounds testing. | As above. |

Tier 3 | High priority offenders | Random testing at a higher probability than Tier 2. They are also subject to reasonable grounds testing. | As above. |

Tier 4 | Highest priority offenders with an alcohol abstinence condition | Alcohol detection anklets. Offenders in Tier 4 remain in Tiers 1, 2 or 3 for random or reasonable grounds urine testing for drugs. | Police will identify their highest risk electronically monitored (EM) defendants on bail for management with alcohol detection anklets. |

External qualitative evaluation

The primary evaluation for this trial was a fieldwork-based investigation of its implementation. This was outsourced to contracted evaluators, Malatest. The main findings of this quantitative evaluation are presented in a companion article by Jill Bowman in this issue of Practice.

Internal evaluations

Three other evaluations were completed by the Department’s Research and Analysis Team. The first was a 10-month progress report to 30 June 2018. The next was a quantitative evaluation completed in December 2018. A final evaluation was completed in April 2019, which provided an overall assessment of the trial and a view on a national implementation.

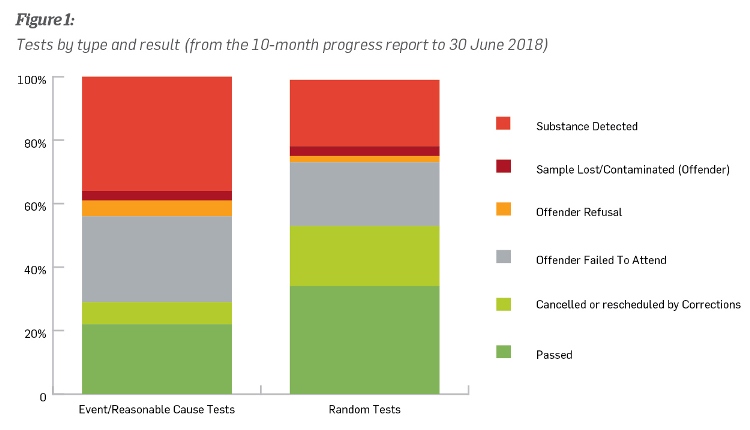

The first progress report found that since the change in legislation the proportion of sentence starts with abstinence conditions had more than doubled. This indicated that judges felt more confident imposing conditions they knew were able to be monitored. The report also highlighted what was happening in terms of testing, such as the proportion of positive and negative tests, failures to attend tests, refusals to attend and cancellations of tests. Figure 1 indicates the results for event based/reasonable grounds tests and random tests.

The results from the first progress report allowed for a better understanding of the behaviour of people, staff and systems. For example, if a person did not attend their test the probation officer was likely to impose a sanction that reflected only the non-compliance (as the probation officer had no more information about the person other than that they didn’t attend). Identifying the main reasons for people not attending allowed the Department to put in place mechanisms to increase compliance with testing, such as increased use of mobile testing vans.

The second progress report, completed in December 2018, provided reconviction and administrative data. An analysis was undertaken to determine the extent of behavioural change among people with abstinence conditions who were subject to testing. The findings were based on comparisons between people managed on sentence prior to and following the introduction of testing. Comparisons between regions were also made because the trial was based in the Northern Region.

The report found that since the beginning of the trial, there has been a decrease in the proportion of people sentenced to short terms of imprisonment and an increase in the proportion sentenced to intensive supervision. This may suggest the judiciary feel more confident about giving community-based sentences knowing that the person’s use of alcohol and drugs can now be more effectively monitored. It is too early to properly assess the long-term impact of the testing on re-offending rates. However, the potential for testing to keep people out of custody, both at sentencing and following breach action, must be seen as a positive outcome as it suggests the judiciary are confident we are able to manage a person’s risk of alcohol and drug related offending in the community. This is important as a person has more chance of maintaining accommodation, employment, and relationship ties if they remain out of custody.

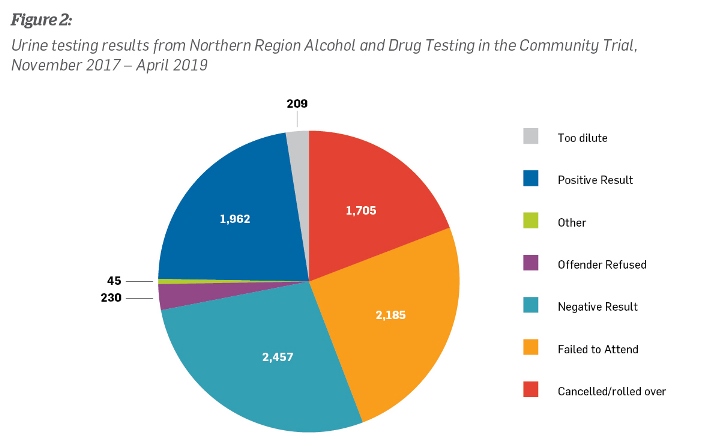

The third and final evaluation of the trial, completed in April 2019, brought together all the information gained from nearly two years of testing – approximately 8,000 urine tests (see Figure 2) and over 120 people subject to an alcohol detection anklet.

“Cancelled/rolled over” tests are those tests cancelled for a legitimate reason (e.g. the person has gone into custody or moved out of the testing area) or “rolled over” because the test has yet to be completed for the month the data is collected, or because we are waiting for the result to come back. The “failed to attend” category indicates that the person either simply failed to show up, or failed to tell their probation officer the reasons they would be unable to attend (e.g. not allowed to leave work that day). If a person fails to attend, probation officers have a range of actions available to them – from engaging with whānau and support people, to a verbal warning to formal breach action.

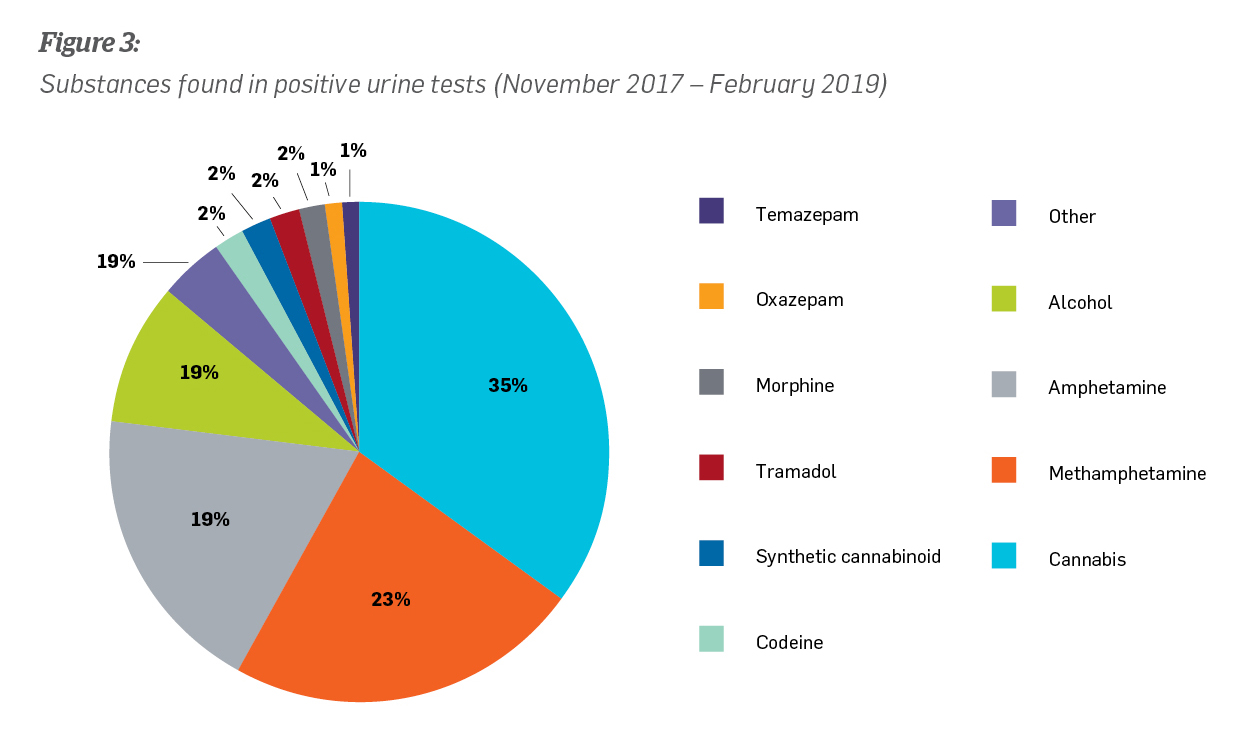

Of the positive urine tests, Figure 3 shows us which substances are being found. Of the 2,060 failed tests, 994 (48.3%) returned a positive result only for cannabis and/or alcohol, 426 (21%) for methamphetamine alone, and 300 (15%) for some combination of alcohol, cannabis and methamphetamine. This provides some context to the gravity of substance use issues amongst our offending population.

At April 2019, alcohol detection anklets (ADA) had been trialled with approximately 70 people on a sentence/order. ADA technology is suitable for that percentage of the testing population that is at high risk of causing alcohol-related harm. While those subject to ADA had a high percentage of sober days overall at 97%, 22 were found to have used alcohol at least once while subject to the anklet. Effectiveness of ADA on recidivism rates is still relatively hard to measure, as only 34 people have been off sentence long enough for it to be relevant. However, of these 34, recidivism rates are found to be comparable with those who have not been subject to ADA.

The final evaluation draws three key conclusions:

- The practice of alcohol and drug testing has been successful in that: “Probation officers are regularly recommending abstinence conditions, these conditions are being imposed by the courts, offenders are being assigned routinely to testing tiers, and probation officers are directing offenders to undertake tests.”

- Testing in the Northern Region has seen a rise in pre-sentence reports that recommend rehabilitative sentences with abstinence conditions. There has been a corresponding increase in the imposition of these sentences, particularly intensive supervision. There is also some evidence of this being the case with parole assessment reports and the New Zealand Parole Board releasing people on parole with abstinence conditions. Re-offending rates have not risen, indicating that this change in practice has not compromised public safety.

- There is some indication that the rates of re-offending and imprisonment are lower for those people on a higher testing tier. This could mean that testing at a higher frequency may be more effective in reducing re-offending.

Practice audit

An internal practice audit was completed in June 2018 for people with abstinence conditions. A total of 235 probation officer files were reviewed for the period 1 December 2017 to 1 June 2018 (six months). A number of changes in practice had been implemented in a short time and this was an opportunity to see how well these had been incorporated, including whether the additional information obtained through testing was enabling staff to identify appropriate pathways for those with alcohol and drug needs.

The audit also checked whether probation officers had understood the Department’s stated purpose behind the changes; testing was not about “catching people out”, but an opportunity to better understand people’s drug and alcohol habits and direct them to the right services for better outcomes. Long-term habits and addiction are not easy to break and international research and experience tell us that testing for alcohol and drugs is most effective in reducing re-offending when it’s done alongside appropriate interventions. Corrections staff have a suite of rehabilitation interventions available and once they know the alcohol and drug behaviours of those they are managing, they can identify the most appropriate intervention for each individual. Testing is therefore another tool, alongside programmes and motivational approaches, that allows us to support change and help keep communities safe.

The results of the practice audit were extremely encouraging. It found that 99% of individuals were allocated to a testing tier, 94% of individuals were referred to an appropriate provider if they had a condition for treatment and 93% of individuals were completing an intervention that matched their assessed alcohol and drug need.

The audit also found that probation officers were responding appropriately to positive tests. For example, if a probation officer had used a sanction (e.g. verbal or written warning) following a positive test, in 61% of cases they had taken another action as well (e.g. referral to programme, brief intervention, third party engagement).This showed that probation officers were taking a rehabilitative approach that was likely to be more effective in reducing re-offending.

In 88% of cases there was clear evidence of an AOD pathway being created for the person, with 76% of people involved in planning their own pathway. In 73% of cases there was clear evidence the probation officer was supporting the person to complete their intervention.

Some of the practice challenges included a low number of Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) assessments being completed with people during their current sentence/order (for the review period), low rates (21%) of involving third parties in supporting AOD activities and goals, low rates (19%) of involving other staff in the management of AOD cases, and insufficient consideration being given to changing testing tiers when a person tested positive or negative – only 21% of practitioners evidenced good practice in this area. It is worth noting that some of these low results could be attributed to staff not recording their good practice in the Integrated Offender Management System (IOMS) rather than a lack of engaging in good practice with the person.

Conclusion

The alcohol and drug testing trial has successfully implemented different testing methods and new practice among probation staff.

Knowing that testing is occurring and that abstinence conditions are being monitored by probation officers may mean judges are more likely to impose community-based sentences and less likely to sentence people to prison. This is a positive outcome as we know that short prison sentences can mean people lose jobs and accommodation and struggle to reconnect with their community when they leave prison, thus increasing their risk of re-offending.

Once the trial has concluded on 30 June 2019, decisions will be made about how a national rollout will be implemented and whether any adjustments need to be made to the testing programme.

References

Lewis, N. (2018) Alcohol and other drug testing trial of community-based offenders Practice; the New Zealand Corrections Journal, Volume 6, Issue 1, 37-41, Department of Corrections